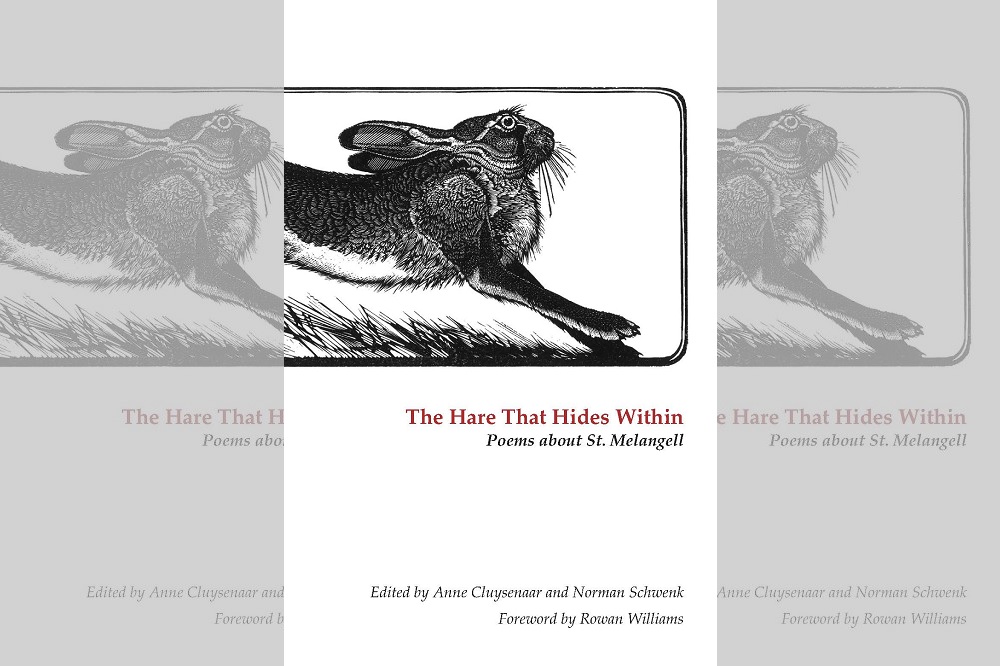

The Hare that Lies Within and the legend of Saint Melangell

Twenty years ago, the poet and teacher Norman Schwenk, who died earlier this year, edited a poetry anthology with Anne Cluysenaar about the story of St Melangell which became a best seller.

Parthian Books have now reprinted an anniversary edition, including the original introduction by the late Anne Cluysenaar.

Anne Cluysenaar

It is impossible not to be surprised by the unique place in which St Melangell chose to settle. Ringed by hills, the narrow valley reaches towards what at first seems a dead end. As far as vehicles go, that is just what it is, but suddenly one catches sight of a long thin waterfall in the distance, whose brightness both closes off the valley and seems to open it to the sky.

Near the road’s end, the grey church occupies a circular bronze-age site. The present shape of the building dates from the fifteenth century, but a twelfth-century church and shrine preceded it, and in fact Pennant Melangell has been a place of pilgrimage and sanctuary for well over a thousand years.

The legend tells how Melangell, daughter of an Irish prince, found in this quiet valley a place in which she could follow her divine vocation.

One day Prince Brochwel, to whom the land belonged, was hunting a hare. A seventeenth-century account tells how his hunting dogs pursued the hare to a thicket of brambles, full of thorns. In it he found a beautiful young woman praying.

The hare was lying under the folds of her garment, fearlessly facing the dogs. Even so, the prince urged his hounds to attack, but they retreated howling.

He then asked the woman how she had come to live on his land in such solitude. She said she had become aware that her father intended her to marry ‘a great and generous Irishman’ so, ‘under the guidance of God’, she had left her native land and come to Wales in order to live out instead a life of prayer and contemplation.

She had not seen a human face for fifteen years. Prince Brochwel knew that God must have given refuge to the hare in recognition of this young woman’s sincere and courageous faith. He did not hesitate now to call off his dogs.

He also gave Melangell all the surrounding lands ‘for the service of God’, and as sanctuary for ‘any man or woman who has escaped here’ on condition only that they in no way pollute the place.

The legend tells that the saint lived in the valley for thirty-seven years. Her way of life was such that wild hares surrounded her as though they had been tame and, as the years went by, she attracted to Pennant Melangell women who wished to join her in a quiet and stable life of prayer.

Beast of legend

In recent years, the legend of Saint Melangell has attracted increasing attention from poets in Wales. They have explored a range of different, even contrasting, meanings, revealing the complexity of what might seem at first hearing quite a straightforward tale.

The hare is itself a beast of legend. Primarily seen as a creature of the Moon goddess, an emblem of fecundity and increase, it has also acquired many names.

Most relevant to the poems in this collection are, perhaps: the fast traveller, the way beater, the slink away, the one it’s bad luck to meet, the dew-flirt, the wood-cat or puss.

Depending on which roles are taken to be primary, the significance of Melangell’s protection, which is ultimately that of God, can be seen to shift.

This very aspect of the legend is drawn to our attention by Ruth Bidgood when she imagines that the hare itself is aware of undergoing a change of character as it accepts sanctuary, surely a delicate emblem, this, for changes that may come to a human being able to feel himself or herself under divine protection.

Prince Brochwel’s decision not to continue the hunt but to provide a sanctuary not only for Melangell and for other human beings but also for wild beasts, has been interpreted as of ecological significance, an indication of the presence of the divine in all living things.

Remembering the Mabinogion, R.S. Thomas wrote in ‘The Minister’ (1952):

“God is in the flowers Sprung at the feet of Olwen, and Melangell Felt his heart beating in the wild hare. In some of these poems there is also recognition of a sexual element in the confrontation between a powerful prince and a solitary virgin. We are led to recognise the overwhelming nature of an experience which could hold such a man back, not only from hunting legitimate quarry but also from violating an unknown woman’s sanctuary of thorns. In this interpretation it is as though the hare, symbol of fertility both natural and sacred, has become an emblem of the most intimate aspects of human existence and survival.”

Deeper realities

Since the earliest days of human prehistory, certain places have been valued as ‘threshholds’ over which the imagination may step towards deeper realities than the everyday. Pennant Melangell is such a place.

Even to the saint herself, it must have seemed already ancient. Perhaps she would have recognised traces of prior occupation. Certainly the great yew tree near the church must have been some six hundred years old when she sat beneath it. She would have been aware of lasting things and short-lived things, and of her own place among them.

No matter what the visitor’s spiritual perspective, Pennant Melangell is full of resonances. While visible forms may alter over time, anyone visiting the place will still be aware of a threshhold tension, a sense of now and forever.

Saint Melangell’s shrine is of a kind we hardly ever see elsewhere. Most such shrines, if they survived the middle ages, were destroyed at the Reformation. Saint Melangell’s shrine was indeed broken up but sensitively rebuilt in the early 1990’s, using as guides fragments of the original structure.

The nave and chancel are separated by a beautifully carved fifteenth-century Rood Screen depicting the legend in impressively simple terms. The carving of the legend is underlined by a frieze of oak-leaves; at one end, significantly, we see a Green Man, oak-leaves spilling from his mouth; at the other, a hand holding a vine, perhaps, as A.M. Allchin remarks, a symbol of the creative power at work in nature.

For centuries the legend of Melangell, and Pennant Melangell itself as a numinous threshold, have stimulated poets to write in both the languages of Wales. More recently, in Allchin’s words, ‘among Welsh writers who work in English, Melangell has been evoking new and original responses’.

It is now ten years since the shrine was restored and became again a year-round centre for pilgrimage and healing. This collection of modern poems inspired by Saint Melangell is published in celebration of the continuing impact of both the place and the legend on the poetic imagination of Wales.

August, 2003 from The Hare That Hides Within edited by Norman Schwenk and Anne Cluysenaar

Catch up on last week’s article with a foreword by Rowan Williams here

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

A special place, truly worth a visit.