Women in Welsh jazz

An ambitious plan to to encourage education, diversity and opportunity for jazz musicians in Wales, especially women, was a huge success. Nigel Jarrett explores the issues that prompted it.

Incredible but true: a woman saxophonist was approached by a male promoter after a gig at a British jazz club and told, after his formal thanks and congratulations, that he would love to be the instrument she put to her lips each night.

One has to take a breath for a few seconds to understand what was meant there, what was going on, and how banter can conceal abuse and ingrained prejudice. I can vouch for the anecdote: it was told to me by the musician herself in a mood of weary resignation.

It said a lot about women’s place in music and the generally alpha-male atmosphere in which jazz is organised and presented.

A woman’s place in Welsh jazz has traditionally been the same as her place in jazz itself: sometimes as a singer and rarely as an instrumentalist. All that has been changing, in Wales no less than in the rest of the jazz world.

But the idea of jazz as a male-dominated industry, at the level of both performance and management, persists. It is still in many cases a reality and reflects what goes on elsewhere. Only in comparatively recent decades, for example, have symphony orchestras admitted female members.

Personalities

A pictorial history of jazz, despite the significant musical personalities of Bessie Smith, Ella Fitzgerald and Billie Holiday – each one a singer – will consist mainly of male bands and male iconoclasts.

Women composers, too, have worked beneath an obscuring shroud, and are only now being re-discovered; that’s because they hadn’t been barred or discouraged in the first place from taking up composition as a profession, like so many of their sisters.

This was the background to a pan-Wales Archwilwyr Jazz Explorers project, which culminated in a concert at Abergavenny called Women In Jazz, featuring a seven-piece band led by Paula Gardiner, head of the Jazz course at the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama.

The project began in July in a partnership with the Aberystwyth Music Festival, which featured a fringe jazz line-up. In September, north Wales became involved, with the Galeri music service in Caernarfon and a group of recent RWCM&D graduates.

The final, Women in Jazz, event was organised by Black Mountain Jazz at the borough theatre in Abergavenny. Performing standards and original compositions, the band also included Liz Exell (drums and percussion), Siobhan Waters (vocalist) Xenia Porteous (violin), Jane Williams (vocals, piano and ukulele), Deborah Glenister (multi-instrumentalist) and Maria Lamburn (viola and clarinets).

The music was sparkling, original and – considering the band members don’t perform with each other as a seven-piece – astoundingly fresh and varied. As well as their own compositions, the members played while video biographies were screened above them.

Chauvinism

The women’s problem in jazz reflects male chauvinism in wider society, reinforced by commentators and so-called ‘influencers’, and often by male musicians themselves as well as those who present the music. Jazz has not been a healthy environment for advancing women’s rights and expectations.

Male-female partnerships in jazz which might appear to militate against distaff prejudice, such as Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong, Lester Young and Billie Holiday, Sarah Vaughan and Billy Eckstine, and John Dankworth and Cleo Laine are paradoxical exceptions, or arrangements in which the women as personalities are as strong as the men.

Like most prejudice, anti-women feeling filters down from groups and individuals who feel threatened.

The British critic Patrick Cairns “Spike” Hughes, who wrote a column for Melodymaker, makes his views plain in Second Movement, his continuing biography first published in 1946 as Opening Bars: “I have always viewed with alarm the growing tendency of women to compose music; not merely because they do not compose very well, but because their presence in the company of a group of male musicians is embarrassing and unnatural. As men we have our own language and our own codes of behaviour among ourselves…There can never be such a thing as true equality of the sexes.” This was prejudice masquerading as chivalry. Hughes admitted there could be parity on wages, perhaps a forward-looking view at the time which jarred with his overall opinion. But he concluded that the Englishwoman (sic) was at her best only when she was dressed for the company “of those horses and dogs which she so much resembles”.

It’s difficult to imagine that such a statement could be made even seventy years ago without tongue in cheek, and even with tongue in cheek it says a lot about the sort of pervading male pre-conception that would allow it to be made without embarrassment or censure.

Hughes was more than influential as a writer and critic. A Cantabrigian, he was also a composer and a power within the BBC, with Oxbridge friends to populate the surroundings that led to exclusion of women.

There’s no doubt that his influence on broadcasting incorporated his anti-female views, the result being that music, and jazz in particular, remained largely an all-male activity. Hughes and people like him compounded the imbalance by seeking to justify what was already obvious.

Those all-male bands across the ages, led by Benny Goodman, Buddy Bolden, Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Stan Kenton, Artie Shaw and Luis Russell, among others, never considered hiring women instrumentalists; not that there were many available even if they’d wanted to.

Fitzgerald sang with Chick Webb, Vaughan with Eckstine, June Christy with Kenton. It was the addition to all-male company of female allure rather than its musical incorporation, but that too.

Male control

It’s interesting to reflect that Fitzgerald’s “scatting” vocalese, though with antecedents, might be interpreted as a means by which a woman singer joined her male instrumental confederates: the voice as instrument.

Hughes was university-educated but he was too dull to recognise that exclusive male language and codes of behaviour could not rationally deny a place for women in music per se; it could only do so under conditions of male control and exclusivity. Exclusion, of course, leads to the reluctance by those excluded to try their hand.

The Welsh angle on all this is more general than specific. But one of the influences on jazz and its musical supplements and offshoots has been the existence of the South Wales ports and their part in creating multi-ethnic docklands societies, notably in Cardiff, once the biggest coal exporter in the world.

Cardiff was shifting 13 million tonnes of coal a year on the eve of the Great War. The SS Empire Windrush influx of West Indians to Britain in the late 1940s, later to change British society for good, had nothing on it in terms of demographic changes already connected with dockland activity.

Purists might argue that jazz has specific origins and characteristics, and this is true; but today’s jazz makes much of its influences, especially when the feature common to them is the skin colour of their practitioners.

Jazz and most of the derivatives that go to define black musical culture are now more likely to be grouped together as relations than studiously separated. There are other roots too.

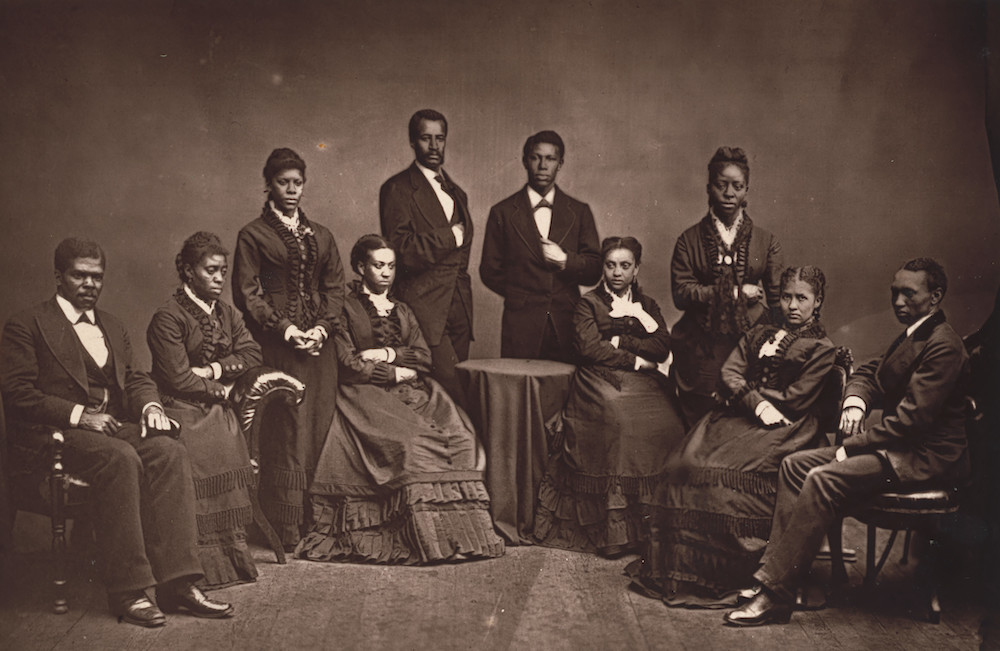

In 1874, while on a European tour, the a capella Fisk Jubilee Singers, from the all-black Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, visited Swansea. At the city’s music hall they performed “strange, weird slave songs”, according to local publicity.

The choir were famous for what we now know as Spirituals, another influence on jazz as recognised today. The Swansea concert was probably given by the Fisk’s 11-piece ensemble, the notable feature of which was that most of them were women.

For a long time after this, and embarrassingly (as we now recognise) into the late 1970s, jazzy entertainment by non-whites was achieved unselfconsciously by men and women “blacking up”. How many of us would admit to being offended at the time by The Black and White Minstrel Show on BBC TV?

Also, the cause of female advancement and representation in jazz has not been helped by the bandying about of the label “jazz” itself; when there’s one cause to fight, distractions are a pain.

The Welsh valleys “jazz band” tradition is peopled by majorette-style young marchers blowing into kazoos, which are refined comb-and-paper instruments. Jazz, it is not, though similar ensembles people the streets of New Orleans at Mardi Gras.

Jazz itself, replete with male-sung ditties about ‘cheating’ women, provides enough evidence of disparity.

Shocking

There have thus been at least two barriers to be surmounted by women jazz musicians – a double-glazed ceiling, as it were: first, the one that bars them because they are female, the second because they are musicians, specifically instrumentalists.

Among the great exceptions to the all-male rule in the distant past were pianist Lil Hardin, a member of Louis Armstrong’s Hot Five and Hot Seven (and, for a while, Mrs Armstrong); pianist Mary Lou Williams, an influence on many male jazzers, including Erroll Garner; and, er, that’s about it. Shocking, is it not?

All this and more is chronicled in the book Freedom Music: Wales, Emancipation & Jazz 1850-1950 (University of Wales Press), by Professor Jen Wilson, jazz musician and founder of the Jazz Heritage Wales archive at University of Wales Trinity St David. Items from the archive’s collection were on display at the Borough Theatre on the night.

Wilson’s book is capacious: it explores the wider culture of popular music in which jazz as we narrowly define it germinated.

Her survey is an important pre-cursor to a consideration of what has happened since 1950, when it could be argued that women in jazz became more populous as male-female imbalances in wider society began to be addressed – and redressed – through protest and changes in the law.

But no-one would deny that such balancing is a work-in-progress.

Other books, including Sammy Stein’s In Their Own Words, have been pleading the case for women as gender equals in jazz.

Paucity

The Abergavenny concert was thus a celebration that times are changing for jazz women. Many volunteers gave their time and expertise to organise the Archwilwyr programme.

In the international modern era, the names of musicians such as composers Carla Bley and Maria Schneider, trombonist Melba Liston, violinist Regina Carter, pianist/harpist Alice Coltrane, pianist Geri Allen, guitarist Emily Remler, vibraphonist Marjorie Hyams; and saxophonist Kasey Knudsen have to be added to the historical paucity.

Female singers today are more original than concessional and they are often instrumentalists too. It’s been a case of all hands to shift the boulder. But at least the blockage is moving and may soon accelerate enough to roll off the path for good.

Freedom Music: Wales, Emancipation & Jazz 1850-1950 is published by the University of Wales Press and is available from all good bookshops or is available here.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.