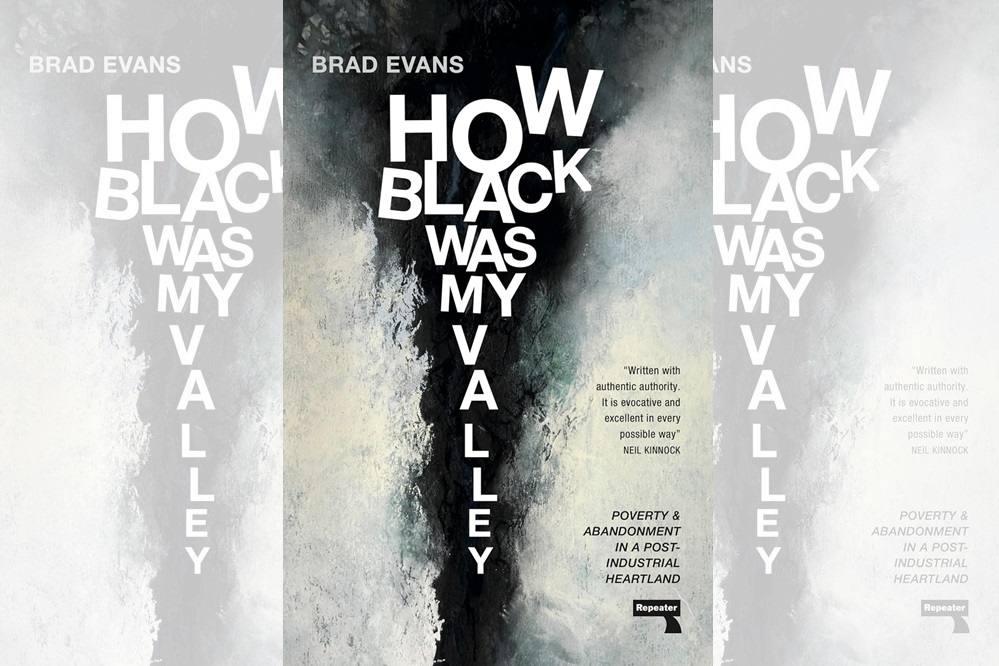

Book review: How Black Was My Valley by Brad Evans

The Truth about the Rhondda?

Author and documentary-maker John Geraint reviews ‘How Black Was My Valley’.’

Anyone who makes a film or writes a book about the valleys – fact or fiction – has to pull off a series of delicate balancing acts if their work is to do justice and honour to the actual lived experience of valley life.

One of those balances has to be between recognising the inconvenient truth that brutalising circumstances certainly do brutalise some, and sometimes many, of those who are forced to endure them; and celebrating the extraordinary achievements not just of our best minds and performers (on stage, screen and playing field), but also of the hundreds of thousands of ‘ordinary’ working-class men and women whose fundamental decency, warmth, humour and camaraderie characterise the valleys I know.

Of course, that working-class deserves a searching analysis of the injustices it lives through, just as much as a platform to project its accomplishments. Hiraeth and Pollyanna-ism won’t change our futures, not for the better anyway.

All the same, I turn to a book with a subtitle ‘Poverty and Abandonment in a Post-Industrial Heartland’ with some trepidation, despite its ringing endorsements from Neil Kinnock, Niall Griffiths, Paul Mason, a Humanitarian Director of Save The Children and a Harvard History Professor amongst others.

Neglected

The words ‘brutal’, ‘neglected’, ‘tragedy’, ‘pain’, ‘violence’ ‘subjugation’, ‘despair’ and ‘suicide’ leap out from the back cover. We’re promised a ‘journey into an open wound’.

As though we might have missed the point, Brad Evans’s introductory statement, covering barely two-thirds of a page, hurls the adjective ‘black’ at us no less than eleven times.

His account proper begins with a chapter entitled ‘A Brief History of Globalisation’. It’s a history glimpsed through the windows of a train trip Evans – now an academic, based in Bath – takes ‘home’ to the top of the Rhondda.

“An old run-down carriage trudges forward by an exhausted motor of monotonous resignation as it barely clings to the precarious and corroding tracks… an empty vessel on a journey to nowhere.”

Newly published, it’s already dated as an account of that journey, as Evans finally gets round to acknowledging at the very end of the book. By now, after a year-long closure for a multi-multi-million-pound upgrade, the Treherbert line is reopening, boasting electrification, spanking new infrastructure, rolling stock and all.

Grim

But the tone has been set. What fills next the three hundred pages is, frankly, overwhelmingly grim. Grim, despite occasional flights of poetic fancy into fable and myth, involving birds, rats and dragons, which sit rather awkwardly against the bleak realism that pervades. We get disease, disaster, deprivation, destitution, death. And rain, of course. Incessant rain.

The working-class glories of the Coalfield are all there somewhere – the historic respect for learning and reading, the democratic instinct and progressive campaigns, the stand against fascism, the hymns and arias, the chapel culture – “more than choral practice. It was politics, and it was life.” – the eisteddfodau and the Ystradyfodwg Art Society (Evans’s great-grandfather was a leading light).

But such is the book’s relentless focus on the negative, we have to dig deep in the text to find any light.

For me, the torrent of blackness obscures the colourful characterfulness and togetherness which engenders love and pride amongst Valleys people – residents and exiles – for their home patch. Missing, almost entirely, are any current shoots of hope, creativity and inventiveness.

Ah well, tell me your truth, to paraphrase Nye Bevan, and I’ll tell you mine…

I have to be careful here, though. I’m in danger of slipping into what Evans warns is the ‘bourgeois fascination with resilience’.

Trauma

My own Rhondda family saw tough times, for sure – a series of tragically early deaths took its women; long-term incapacity afflicted its men due to ‘dust’ and the trauma of carrying out the bodies of workmates incinerated in an underground disaster.

But my mother’s was a ‘family of notable mid-Rhondda craftsmen’ (or so said the Rhondda Leader). Thanks to that, to the Rhondda Borough Council’s investment in education, and to the family’s (overly) strict adherence to the puritanical virtues of thrift and temperance, we escaped the depths of poverty and despair which trapped so many others.

Brad Evans’s family – through no fault of their own – weren’t so ‘lucky’. His writing is at its most powerful and persuasive when he writes of that experience.

“When Thatcher arrived, we were already destitute. Her shame was to make poverty feel a million times worse… Despite the fact that my father was medically declared incapable of working due to the severity of his physical and mental health, he would still be constantly subjected to humiliating means-testing to prove he wasn’t fit for anything… And I will never forget those hopeless tears my mother cried as she left the Department of Social Services building wondering how we would get through another week, every week, knowing circumstances would never change.”

The family curtailed their TV watching in late autumn, to ensure there was enough in the electricity kitty for them to watch the Christmas specials.

Degradations

Evans links these personal degradations of his boyhood to the wider crushing of generation after generation of Rhondda people, which by now amounts, as he points out in a telling chapter, to ‘One Hundred Years of Depression’.

It includes this trenchant reminder:

“A well-rehearsed cliché says children in poverty don’t know they are poor because there is nothing to compare it with. Whoever repeats this has never lived in poverty, like those who say language hurts more than physical harm have never been kicked repeatedly in the head… Poverty is first felt as a microscopic division. Those who have barely anything are made to feel thankful they don’t have nothing at all. It finds ways to shame those without, especially the young, who from their inception learn the relative torments of want… The constancy of poverty is to weave feelings of shame deep into the fabric of time.”

Affecting

One of the book’s black diamonds – if I can put it that way – is a chapter on the Aberfan disaster.

Sensitively written, with a rightly humble appreciation of the ambiguities of any outsider venturing to depict that cataclysm, it’s every bit as affecting as the BBC’s Owen Sheers-driven commemoration The Green Hollow (which is referenced by Evans); every bit as excoriating of the culpable neglect, indifference and inhumanity of the ‘authorities’ as was Iwan England’s 2016 documentary Aberfan, The Fight for Justice.

If the point, though, as Marx said, is not to interpret the world, but to change it, does Brad Evans finally offer any cure for the valleys’ ills he catalogues? If he does, it’s a subtle and undogmatic one, and in fairness to him I hesitate to summarise it in the space available here.

Suffice to say that what he does set his face against is what he calls ‘mobilised victimology’.

“There was a time,” he writes, “when people refused to see themselves as victims of history”.

Though he acknowledges that that in itself was problematic, he’s clear that the swing to “a politics of victimisation is the worst kind of individualism”.

In one uncharacteristically positive passage, Evans declares: “Children of the valleys need to be taught the rich history of these lands. They should learn about how they are all descendants of migrants, how the valleys have a proud past, how that pride was a catalyst for historical struggles against fascists, and how there was once a strident idea of welcoming outsiders…They should be introduced to the likes of Paul Robeson and have a broader appreciation of the history of colonisation, including Wales’s fraught relationship within its divisive systems of rule… And they should be taught more rigorously about the poetry of the valleys, its song and prose, its silences, its myths and its visions…precisely to create a new set of dreamers who may just have the imagination to transform the lived conditions of this black earth.”

Amen to all that. I just wish we could have been given more, and more recent, case studies of valleys people acting with agency, rather than as victims.

‘How Black Was My Valley’ by Brad Evans is published by Repeater Books and is available from all good bookshops.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

great book!!!!

I found this book very affecting and engaging. Yes it’s grim but it offers an unvarnished truth. Too many books on the valleys are romantic or demand balance. It’s refreshing to read an honest account.

Anyone with Brad Evans back story of growing up in Penrhys in the 80s has every right to emphasise the grim degradation that is poverty. His writing is full of eloquent anger. His lyrical style recalls Gwyn Thomas at his least relenting and most declaratory. I am tested by his argument. But I am troubled by his mean spirited version of Rhondda history. The valleys have a troubled often heroic past and a great heritage. Yes, bodies were bent and spirits crushed by exploitation. But the valley is its people and they remain strong. I am proud to know so… Read more »

I read the book yesterday from cover to cover and couldnt put it down. I am a bit lost by the tone of this review and the last comment especially. The book is full of praise for the people of the valleys. Its not “mean spirited” in the slightest. I am a care worker in the valleys and the problems we face are stark. Drawing attention to these is important, it’s based on care.

I don’t deny the stark nature of the problems for one moment. I suppose that like the author many of us are ‘walking contradictions’ not wishing to deny reality but also finding comfort in the mythology.