Sosban Fach: a personal history

Ant Heald

When did I first hear Sosban Fach? Perhaps in the background of a Six Nations match when, as a child who had been to Abersoch, Anglesey and Llandudno on holidays I cheered on Wales with a naive and arbitrary attachment.

I bought little paper flags of the draig-coch to stick on my sandcastles, and saved my pocket money to give my mum a cheap brass plaque with the Lord’s Prayer in Welsh, that hung for years on the wall of our Yorkshire home.

We weave narratives to make sense of our lives as individuals and as members of communities: tribes and cultures, towns and counties, teams and countries.

Had things wound up differently I could be looking back at a nomadic life at sea, sparked by a childhood obsession with lifeboats on seaside holidays, or living in the States working for NASA or Switzerland with CERN, living up to unfulfilled early schoolboy promise as a space and science boffin.

Instead, I have ended up in Wales, in Llanelli, and as an English incomer (Why do I reach first for that word? Why not ‘immigrant’?) reinventing myself as a wordsmith after decades teaching English in Yorkshire comprehensive schools.

I have forged a story founded on a personal myth of Cambrophilia, and now, resident in Tinopolis I try to make sense of my place in this place, and of its place in the world. Without history there is no making sense of now, and no history without a story.

So, what is the story of Sosban Fach, and of how it became part of the story of Wales, the story of Llanelli, and in turn part of my story? So, when did I first hear Sosban Fach?

A new tribe

The first time I can pinpoint with accuracy cannot actually have been the first.

I had been at some earlier point to Llanelli’s old ground, Stradey Park, sneaking through the ‘schoolboys’ turnstile with my Llanelli born girlfriend to watch the Scarlets, but the day I can attach a date to is when we saw them play in the Schweppes Cup Final at Cardiff Arms Park in May 1988.

I must have heard Sosban Fach before then, otherwise how could I have known the words, to the chorus at least, belting them out as Llanelli took the spoils against Neath. I had hated rugby as a teenager, put off by a traditionalist grammar school where if you weren’t good enough to challenge for the first XV it was press-ups in the mud, overseen by a disgruntled history teacher barking orders and blowing cigarette smoke through the gap in the window of his warm parked car.

But here, for an afternoon at least, I could feel part of a new tribe, singing along to the apparently nonsense chorus:

Sosban fach, yn berwi ar y tân

Sosban fawr, yn berwi ar y llawr

A’r gath wedi sgramo Joni bach

That match in 1988 was seventy years after the Welsh language newspaper Y Darian (The Shield) bemoaned a concert held in Llanelli where all the songs were sung in English. “What happened to the Welsh in the town of Sosban Fach?” The writer lamented. “If they experienced what we are in the land of Gwent regarding the disappearance of the language, they would soon come to feel the effect of their folly and the weight of their loss. Llanelli Welsh blush”

Decline

For those who mourn the decline of the language and the culture associated with it, those words should perhaps offer hope, for if a writer now over a century distant from us could exclaim “Gwarchod ni!” — “Protect us!” from the decline of Welsh even in one of its heartlands, the Sosban town, surely we can believe that prayer has been, in part at least, answered.

Even though Welsh continued to be eroded as a community language, at least I cannot imagine now a concert in Llanelli with no representation of Welsh; and in almost fully Anglophone Gwent and Glamorgan, pub walls now ring with football supporters chorusing Yma o Hyd which has been adopted as the national football anthem as quickly and as surely as Sosban Fach became associated with Llanelli and its rugby team.

Exuberant

The story of how Sosban Fach came into being was from the earliest days a matter of dispute, the outlines of which can now be traced in the digitised newspaper archives of the Library of Wales.

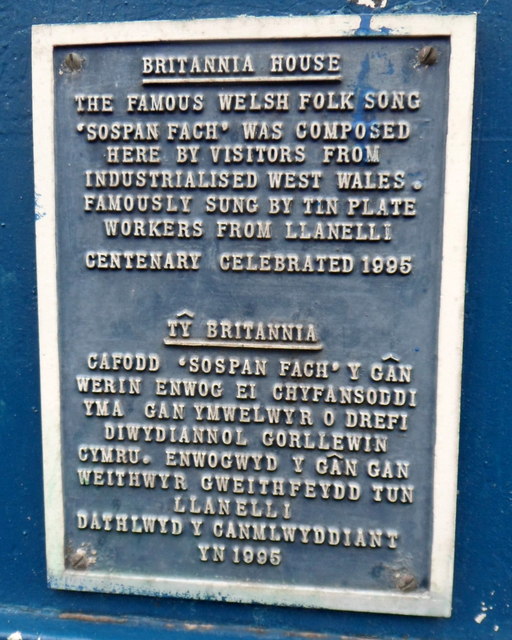

What is certain is that a verse by the bard Mynyddog, written in 1877 formed the nucleus around which some semblance of the song and its tune as we know it coalesced at the Britannia Inn, Llanwrtyd Wells in August of 1895, where a number of Llanelly men were among those enjoying the spa town’s restorative qualities and apparently forming the most exuberant body of the makeshift choir that brought the song to birth.

Within only five months the South Wales Daily Post ‘Football Notes’ column (from the days when rugby football was just ‘football’ in Wales) could declare, “Llanelly are called up the line “The Sospan Fach team.”

The correspondent continued, “A Swansea man told me in all seriousness a couple of days ago that the All Whites would not have lost at Stradey were it not for that thundering ‘sospan bach’ as he described it. ’It completely knocked up our men.’ Neath people don’t like it either!”

Emotional

Neath people probably didn’t like it much in 1988 either, as the ‘Sospans’ ran out 28-13 winners in Cardiff, but one of the lessons of that day for me, with the black shirts mingling alongside the red, so different from the segregation I’d been used to as a soccer fan, was that what united those rugby fans ran deeper than the rivalry that divided them, and I felt its allure, sensing something of its origin, and wanting to make a story from it that I could act a part in.

Joining in an ale-fuelled sing along to Sosban Fach at the Arms Park and affecting a Welsh accent for the half-time urinal banter; reciting aloud without understanding, but with a sense of the beauty of its chiming cadences, the verse of Dafydd ap Gwilym to a Welsh speaking university friend who claimed that somehow I was, weirdly, doing so with an Aberystwyth accent; marrying that Llanelli girl who deepened my emotional connection and gave me a familial link to the land of her fathers: did any or all of this make me in any sense Welsh?

For over a quarter century the question simmered quietly. We made a life and a family in a part of England that neither of us belonged to and never fully felt like home. When football failed to ‘come home’ in ’96 and at later world cups, my teacher wife nevertheless wore the St George’s cross to cheer on her pupil’s heroes.

And in the Six Nations I would drape a Welsh flag in our living room window and sing ‘Hen Wlad fy Nhadau’, justifying it by an etymological sleight: the land of my father was Craven, in Yorkshire — Craven, the scratched land of limestone pavements, derived from the same root as the Welsh ‘crafu’ one of the lyrical variants of what the cat did to little Johnny in Sospan Fach.

Yet still, I cheered as my wife looked on glumly when another Johnny, with the very English surname Wilkinson, dropped the last-second goal that won England the 2003 rugby World Cup against the Aussies.

Home

By 2015 Llanelli was my home — was that now enough to make me in any sense Welsh? — when a work trip to Nairobi saw me arrive at the hotel just as that year’s England v Wales World Cup game kicked off. I expected rugby to hold little interest in football mad Kenya, but went to the bar anyway in the faint hope that perhaps there might be a TV showing the match.

An Irishman, one of only three customers, was indeed watching the match when I walked in. We got to talking and I explained that despite my Yorkshire accent, I was supporting Wales, not England. The other two people in the bar were Kenyans chatting together on a sofa, and as the match went on I realised to my surprise that they were taking an interest in the match.

One of them asked where I was from and when I replied Llanelli, preparing to launch into the usually required explanation that it’s in Wales, no not Tunbridge Wells; no it’s not in England. But he didn’t need any of that.

“Ah, Llanelli!”, he bellowed, pronouncing the LL’s perfectly, and then launched into the most sonorous rendition of Sosban Fach I have ever heard, in his rich baritone.

My new friend for the night, that Welsh supporting Kenyan, told this Welsh supporting Yorkshireman (Why do I reach for that term? Why not Englishman?) that he was a doctor, had trained at St Mary’s Hospital in London in 1968, and had played varsity rugby with a fellow medical student, one J.P.R. Williams.

Hearing Sosban Fach, sung by a black African, surrounded by the gin-soaked and wood-panelled echoes of empire while underdog Wales shocked England to defeat gave the song a new resonance.

We were almost a century on from a story in the Llanelly Star reporting a letter from a Llanelli soldier stationed in Egypt. “There are a number of black troops here,” he wrote, “and one night I sang ’Sospan Fach’ to about 40 of the N—

…” — and here he used what is now a racial slur that seems offensive even to hint at, yet which was blithely used in the headline of the piece. His words now seem condescending and insulting, with their reference to being ‘far from civilisation’, but we surely cannot blame Corporal Williams for the culture of his time.

We can, though, use it as a reminder that not all culture is worth saving, but that what is worth keeping — even an apparently lightweight piece of doggerel nonsense — can be built on, transformed, nurtured and grown: made into something rich and strange, beautiful and deeply meaningful.

Tenacious

Such was the impact of a version of Sosban Fach I encountered a couple of years ago after hearing the late Welsh poet Nigel Jenkins’ daughter Angharad perform with her voice and her violin at an evening celebrating Nigel’s life in Swansea.

I was entranced by her voice and musicianship, and searching for more of her music later, I came across a collaboration between her and the Australian folk band, Bush Gothic – a recording of Sosban Fach that simultaneously made the song wholly new and modern, while excavating haunting roots that tapped into the fertile yet often tragic soil of the history of Welsh speaking Wales and the indigenous peoples of Australia.

Mournful

It did so through a tender and mournful yet tenacious and challenging inversion of the macho gusto with which the song is sung on the rugby terraces, returning the song to the radical Welsh origins of the Eisteddford bard Mynyddog’s original verse from which the lyrics as we know them were embroidered.

The saucepans burning on the fire and on the floor, the crying baby and the scratching cat, the injured hand, and the sickened servant, are transformed from the scene of comic slapstick they have become, into a baleful yet beautiful portrait of domestic servitude that has been through the ages, and remains for many, the lot of most women, and which also echoes the marginalisation of peoples, languages and cultures in their own lands – indeed, in our own land, our gwlad – by the deadening force of colonialism, and the complacent response to its ongoing ripples across the years.

That, surely, is our challenge as people of Cymru, whatever our origin yn wreiddiol; wherever we find ourselves now – to make a culture that is continually renewed by honouring that which is worth conserving and resisting those forces that would prefer us to forget.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.