A Frenchman’s encounter with Mari Lwyd (and praise for the Welsh) at Llanover in 1862

Stephen Price

Llanover, a quaint village on the approach to Abergavenny, is synonymous with Welsh history thanks to the passions of Lady Llanover – a patron of Welsh arts, language, custom and costume.

Passers-by would be forgiven for overlooking a small detail on the village’s old post office – Llythyrdy Rhyd y Meirch. For the old sign, which still stands above the entrance, contains an original painting of the Mari Lwyd commissioned by none other than Lady Llanover herself.

The Mare’s Tale

While searching for images for a recent Mari Lwyd article, I happened upon some correspondence that took place between Clive Hicks Jenkins and Damian Walford Davies that took place around the creation of ‘The Mare’s Tale’ – Walford Davies’ spoken narrative set to music.

The tale was inspired by the Welsh mid-winter mumming or wassailing tradition of the Mari Lwyd, and a collaboration with Hicks Jenkins and composer Mark Bowden.

In their interchange, Hicks Jenkins includes a rather wonderful encounter with a French traveller and a painting of Y Fari in 1862 and Nation.Cymru has been given permission to include the contents of one particularly special entry here, not only for its account of the time spent in Llanover and discovery of the Mari Lwyd, but also for how the author found the Welsh character which is just as apt today.

The Mari Lwyd of Llanover pre-mid-1800s differs slightly from the mare we know today. Her eye sockets filled with broken bottles and lit from within by small lamps – with youngsters dressed to the nines in tow dancing and singing from door-to-door in search of money and merriment. Blue, green and amber eyes glowing menacingly in the winter night.

In Clive’s words:

‘In Le Tour du Monde (Paris. Librairie Hachette & Cie, 1867) Alfred Erny writes of his Voyage dans le Pays de Galles made in 1862. Erny made drawings of what he saw during his time in Wales, and these were engraved by Grandsire for inclusion in the book.

‘I’ve included rather more text here than was strictly necessary given that my prime interest is the painting of the Mari Lwyd outside the post office in Llanover. Forgive me if I’ve erred on the side of too-much-information, but Monsieur Erny writes so entertainingly. I’m much obliged to Lucy Kempton for the translation.’

From Le Tour du Monde…

‘I spent some hours at Merthyr Tydfil, then arrived at Abergavenny, where I visited the castle. The route to Llanover is one of the most charming in Wales, with no harshness in the landscape at all, but only a gentle roundedness in its hills and mountains which caress and relax the eye after the aridity of Merthyr and its surroundings.

‘Port Mawr, the main entrance to Llanover, is an exact repilca of the ancient gate which the Tudors destroyed many years ago at Abergavenny. On the pediment is carved an inscription in Welsh which I shall quote here for its flavour of antique hospitality:

Traveller, who art thou? If friend, then welcome from the heart; if stranger hospitality awaits thee; if enemy goodness will restrain thee.

‘Passionate about all things Welsh’

‘Descending from the carriage, I thanked Lord and Lady Llanover for their kind invitation to spend some days at the castle. Lord Llanover had for some time been a minister of finance and is now the Lord Lieutenant of his county. Lady Llanover is a person of great energy and passionate about all things Welsh, defending in every case the Welsh language and customs from attack from the ill-will of the English.

‘The latter wish to operate by the same principle of absorption which has succeeded in Scotland and Cornwall, and to assimilate the inhabitants and the indigenous language in the same way as in those two countries.

‘But there is still a lively spirit in Wales, which has preserved its own language and character. Indeed, there is no one more different than an Englishman and a Welshman – the former has a stiffness immediately apparent, which does not exist in Wales. The Welshman, like the French to whom he is much closer both in character and manners, is much more open and much more inclined himself to approach the traveller.

‘The Welshwoman too, from the indomitable blood of the Cymri, has something proud and original about her. In her conversation she has more zest and gaiety than an Englishwoman; a Welshwoman with only a few words of French will willingly engage in conversation with a traveller and almost guess his thoughts – this could never happen with an Engliswoman.

‘The welcome they gave me was as cordial as it was gracious. Lady Llanover led me immediately to the gardens, where I was halted by the sight of a gigantic rhododendron of a hundred and fifty feet in circumference. In the middle of a small wood, I beheld nine fountains from nine springs, which ran as abundantly in summer as in winter, and which never dried up even in the driest of seasons.

‘Further on and across the park we arrived at the village of Llanover. Lady Llanover, who looks after everyone well, accompanied M Martinet and myself there. She stopped at several houses and shared encouragement and kind words with each of her tenants. The interiors of the farms were noticeably well cared-for, with scrubbed furniture, polished iron stoves and gleaming floors, as clean as Dutch houses. I remarked to M Martin the difference between these and Breton homes.

‘Speak no ill of the Bretons’ observed Lady Llanover ‘for they are our brothers. To the Welsh, Brittany is a sister country, and they call them our brothers from Gaul.’

‘In one of the cottages, the mistress of the house showed us a magnificent carved wooden staircase which must have been hundreds of years old.’

‘Fight it out’

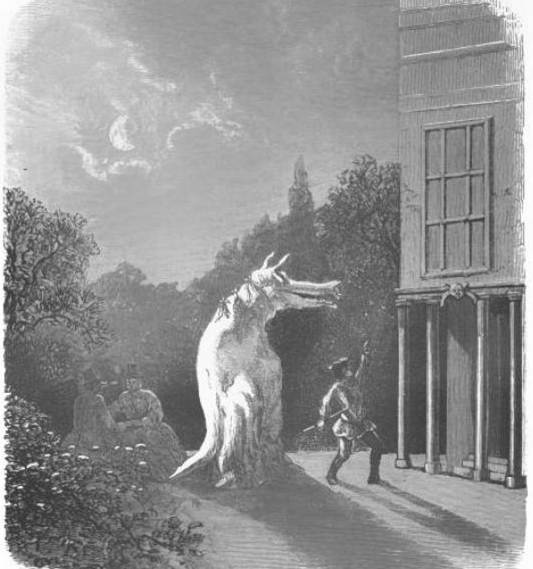

‘A small inn drew my attention by its extraordinary sign. It was an oil painting showing a fantastical scene, a kind of bizarre apparition. I was told that it was painted, from life, at the time of the last Mary-Lewyd, and they explained to me about this old and curious custom, which has now died out like so many others.

‘On the night of Kings [Epiphany or Twelfth Night], the young people would procure the skeletal head of a horse and decorate it with silk rosettes and ribbons in every colour. In the eye sockets they would put two broken bottles with a small lantern in each of them. Twelfth Night was called in Wales the Night of the Mary-Lewyd.

‘A boy would put his head inside the skull, cover himself with a white sheet and parade this kind of phantom from house to house, collecting money. Three young people dressed in fantastical costumes would come behind the spectre, doing a particular dance, then on leaving used to sing a charming tune which was also called the Mary-Lewyd.

‘Like the Bretons and the Basques, the Welsh had the habit of contention between parishes. The excitement generated by these rivalries was incredible. To settle their claims, they would often come together on an open area where each side would fight it out in front of a large crowd of spectators.

‘Nowadays, an old woman of Llanover told me, the youngsters don’t enjoy themselves the way they used to, with all kinds of games. However, this giving up of the popular old games has its compensations, since now the young people occupy their leisure time in composing music and writing verses and essays in the hope of winning prizes at the Eisteddfods or the bardic gatherings which take place every year.

‘This fashion helps to preserve the language, the national literature and the culture of poetry for which the Welsh have such an aptitude. The most striking example is that of Pennillion, which demonstrates the talent for improvisation which the Welsh, like the Basques and the Bretons, possess.

‘Two competitors sing, with or without harp accompaniment, in stanzas called Pennillion. The first improvises the verses and sings them, the second takes up the tune and replies in a satryical and comic fashion. Other improvisers follow, and until they find a champion, this joyful combat can go on for a whole night.’

Translator’s Note:

The original had no punctuation, but fortunately it did have capitals, so I went through and added it as I saw fit, and in places there seemed to be words missing or rather weird mistransliterations so I interpreted what I thought they must have meant!

Only a small part of it – which read fairly clearly – is about the Mari Lwyd, but it’s an amusing and interesting read, and kind of telling as to how travellers have always projected their own agendas, preconceptions and states of denial onto the places they visit. It amuses me how he lavishes praise on the Welsh in the highest form possible, ie by saying they greatly resemble the French (no change there, it’s still the greatest compliment they can pay you here, to say you look/sound/are ‘nearly’ French!) and demonises the English for their policy of cultural hegemony and absorption, which was pretty much identical to that pursued by the French to their linguistic and cultural minorities, only less fiercely ideologically justified. Happily, good old Lady Llanover, who by all accounts was indeed quite a trooper, rounds on him when he alludes to the dirty Bretons!

In the last bit, the reference to the youth of the different parishes ‘battling it out’ I wasn’t sure about. The expression is ‘renvoyer la balle’ which is now used mainly figuratively, but might have meant a literal game of football – or perhaps some kind of proto-rugby! – at that time.

I was amused at the old lady’s lament about the youth of today and how they spend all their time writing music and poems for the Eisteddfod instead of beating each other up like they used to! (I am also aware the plural of Eisteddfod is Eisteddfodau but thought that might be over-egging!).

I observe that even at that time, in that area at least, the Mari Lwyd custom was considered to have died out.

Lucy Kempton

With thanks to Clive Hicks Jenkins and Damian Walford Davies, and Lucy Kempton for her fine translation – an important addition to Wales’ cultural legacy.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Although I am a great supporter of Welsh customs, I would like an explanation of why there are very similar customs involving a horse’s head and knocking on doors in Cheshire and Kent.

My theory is that the majority of Britain is made up of Britons, Anglo Saxon culture has been highly exaggerated and the Mari Llwyd is an oral reference to Troy and how the Trojans (Inwhich all ancient Britons claimed descent) were tricked by the Greeks. This would go a long way to explaining why the Romans spared Caradogs life when they captured him as opposed to doing their usual Thing of Be-heading the leader of native peoples. If the Britons were Trojans, that would make them and the Romans Kin. A few centuries removed ofcourse.

I wonder if ‘renvoyer la balle’ might refer to Cnapan or something similar, although I understand Cnapan to have been more of a west Welsh game.

There is much more to Llanofer and her ‘Welshness’. See the cottages and (Cymraeg) memorial erected by Lord Treowen (grandson of the Lady) in the village. His own son, Elidyr was a Great War casualty, he retired from public life following unveiling of Newport’s civic memorial.