Bernard Mitchell: A Portrait of the Portrait Artist

Sarah Morgan Jones

The National Library has become home to the vast collection of portraits taken by Welsh photographer Bernard Mitchell.

For the best part of six decades Mitchell has been a photographer, with a significant part of that time spent photographing the literary, artistic and sometimes musical greats of Wales, observing them in their own environments and elements.

His collection includes giants such as Kyffin Williams, Joseph Herman and RS Thomas, and friends and contemporaries of Dylan Thomas, Vernon Watkins, Daniel Jones and Ceri Richards.

Among the women he captured were Glenys Cour and Joan Baker, Ruth Bidgood and Gwyneth Lewis, Mererid Hopwood, Menna Elfyn and Kusha Petts, to pick out just a few.

Having acquired the collection, after some years of it being loaned to the Richard Burton Archives at Swansea University, the National Library plans to undertake a not insignificant project to digitise the portraits and make them available online for educational purposes, as well as providing access to them in person in the archives at Aberystwyth.

Meeting Bernard for the first time properly at the Nigel Jenkins Literary Award ceremony, he doesn’t not feel like a stranger as he tells me with satisfaction the library news.

He is rightfully delighted that the work will be preserved for future audiences and that students of his subjects, many of whom are now long gone, will be able to find out what the artists and writers who epitomised the Welsh cultural scene of the mid to late 20th Century Wales really looked like and see where they worked.

Lucky Leica

Bernard didn’t feel like a stranger because, I feel like we have met before. Indeed, I attended his daughter’s wedding many moons ago as the plus one (and driver and kit-carrier) to my musician husband who serenaded the newlyweds at the ceremony.

Through his long friendship with my husband, I have heard many a ripping yarn about the man, who started out as a photojournalist before taking it upon himself to document the artistic population.

The classic tale of the ultimate lucky break, told to me many times, occurred when a very young Bernard took possession of a 1932 Leica, borrowed on approval from Evan Jones’ camera shop in Swansea’s Wind Street.

He was using it to photograph trawlers unloading at the docks, when an explosion shook the town – the Gasworks on Oystermouth Road had blown up, filling the air with burning gas and thick black smoke.

“My guardian angel had arrived in splendour,” he recalls on his website. “There followed three pictures on the front page of the South Wales Echo and on the following day in the Daily Telegraph.”

With that, the debt of his Leica was cleared and “my life as a photographer had begun”.

Inch-by-inch adorned

A week or so after the Nigel Jenkins do, I am sitting in his cosy home drinking coffee and listening to more ripping yarns from Bernard, in the company of his wife Anne, surrounded by walls which are inch-by-inch adorned with paintings and pictures gifted to him by the many artists who have become his friends.

He reels off the names of them asking if I know their work and the fact of my relative ignorance of who is who does not deter him or embarrass me.

He explains that the paintings have come as gifts from the artists themselves or from their bereaved families and observes that he is running out of wall space.

He also observes, matter of factly, that so many of the people he has collected beneath the lens have now left this world and that his photographs remain as a memory of them.

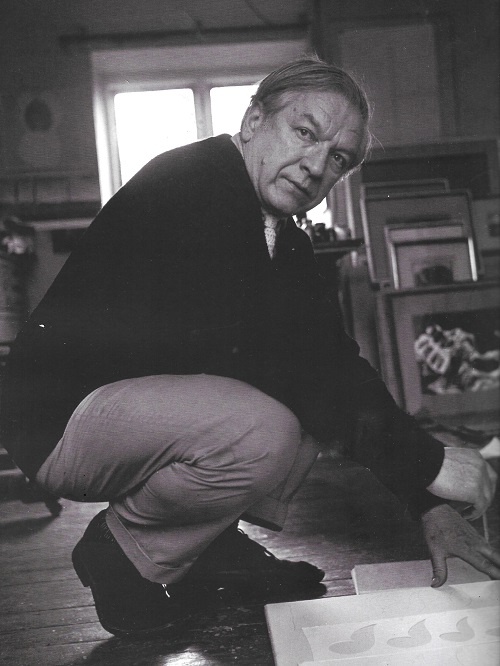

“Ceri Richards was the first artist I photographed, in 1966. Ceri Richards was, I think, the best artist ever to come out of Swansea and I was a great fan of his work, and very influenced by him when I was young, when I was a teenager. I went and saw his work at the Glynn [Vivian] and I thought ‘Wow. Who’s this guy?’”

He later discovered that Richards was one of a group of people who came out of Swansea who were considered ‘geniuses in their own right’, and all happened to be friends of Dylan Thomas.

“Although Ceri met Dylan late in life, you had Alfred Janes who shared a flat with Dylan in London, Vernon Watkins, the poet who lived in Pennard, and Daniel Jones the composer from Mumbles…I called them the Swansea Gang, although many called them the Kardomah Boys as they used to gather in the old Kardomah café before it was bombed in the war.”

Bernard photographed these men as part of a college project, including in the array the piled high shelves of bookseller Ralph ‘The Books’ Wishart, from whom Dylan would borrow a book and take it along to the nearby BBC building to record ‘A Book at Bedtime’, before returning the book to Ralph, with no money changing hands.

Reaching for his own book ‘Pieces of a Jigsaw’, which was published by Parthian three years ago, Bernard shows me the picture of Ceri Richards.

“Here he is…in this picture he is sketching out the designs for the windows of Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral.”

Out of the darkroom

When he left school Bernard knew he wanted to be a photographer and set about hunting down jobs in journalism which would enable him to realise this ambition.

“The only way to make money as a photographer was to get a job on a newspaper. I wanted them to pay me to be a photographer and to pay me to travel,” he told me as he recounted his early days learning the ropes.

In a coincidence which is so typical of Wales and Welsh storytelling, he encountered a photographer on a newspaper in Berkshire, Haydn Jones, who recognised his work having previously developed his gasworks images and pointed him in the direction of a job for a new newspaper under the Thomson news umbrella.

Although he didn’t get that job, they did take him on as the dark room tech, where he learned hard and fast the arts of the dark room, developing the work of nineteen photographers, before finally getting ‘out on the road’ himself.

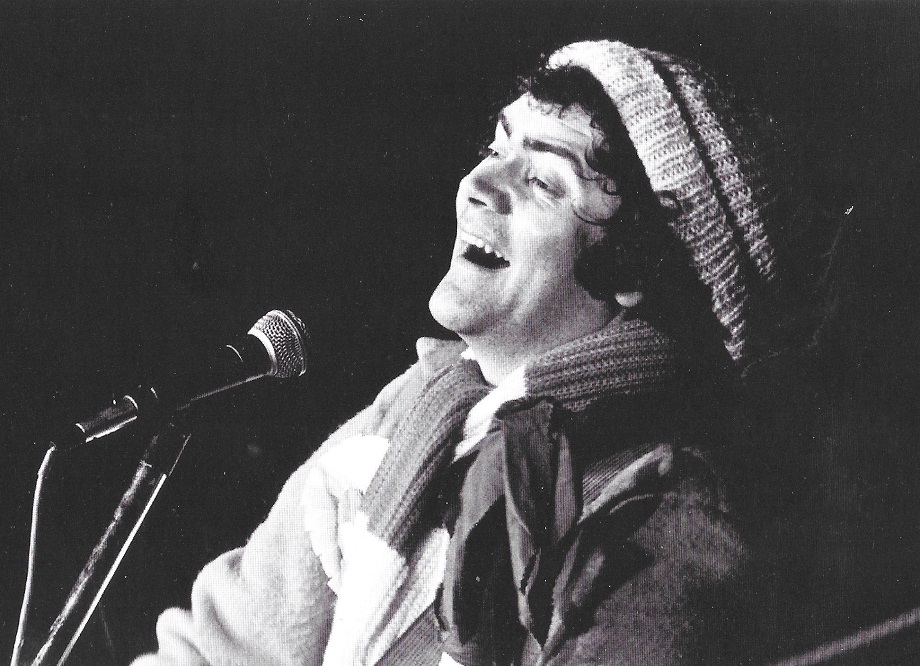

His freelance work for the Guardian arts column sent him to Wales to record the rising star of Max Boyce, and as well as visiting him at home in Glyn Neath he also took shots of the Albert Hall concert which went on to be used in Boyce’s book – with just a token payment eventually and reluctantly agreed.

Life’s work

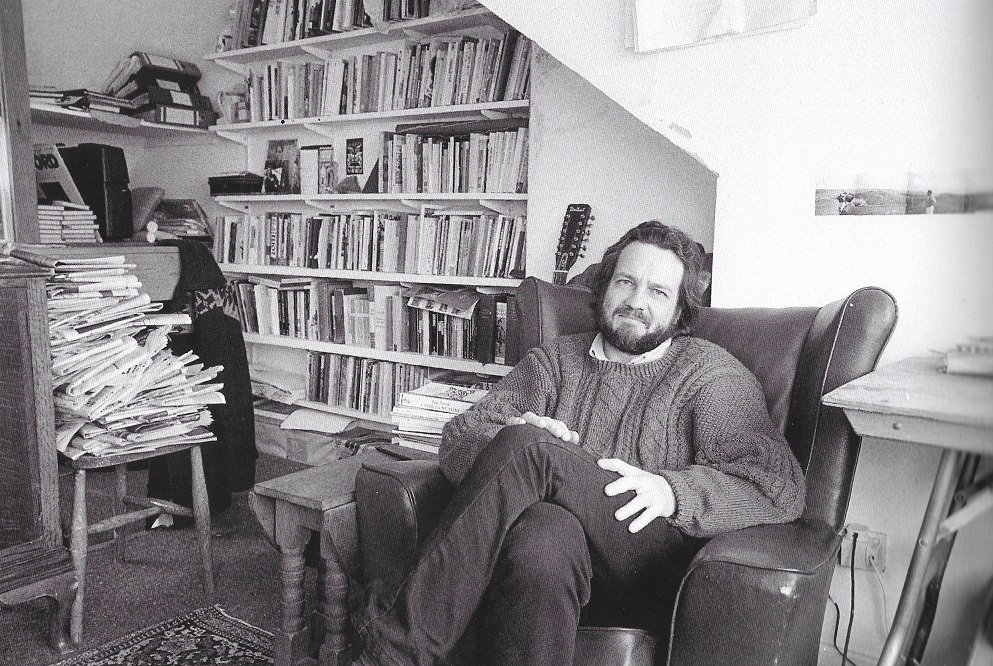

But it was when he moved back to Wales in the late 80s and subsequently acquiring some funding from the National Library to pursue the portraiture, that he embarked his life’s work of documenting the Welsh arts world.

He recalls going to see Kyffin Williams to take his photograph.

“I asked him ‘Could you give me a list of six people you think I should photograph for posterity, important artist and writers…’ because, you see, I think artists and writers work together, they are symbiotic…

“So, this is what I did – I started using the artists to give me the information about who I should photograph. I don’t know why I chose Kyffin to ask, probably he was the only person who I knew and because he was ‘Sir’ Kyffin, the only Welsh artist to be knighted.

“Anyway, top of his list was Will Roberts from Neath… ‘Will Roberts is the best painter in Sarth Wales,’ Kyffin said, ‘Sarth Wales’ … because he was posh. Will was very influenced by Josef Herman, and top of Will’s list was John Petts…”

Crossing borders

Bernard turns the pages of his book with each ensuing image prompting another vignette, remembering how the network developed and gathered to share and interact, some of them regularly meeting in the pub on a Tuesday night – the Tuesday Club.

The collaborative nature of their artistic collective crossed borders, taking exhibitions to Belgium and the Czech Republic, putting the vitality of cultural exchange at the heart of their mission.

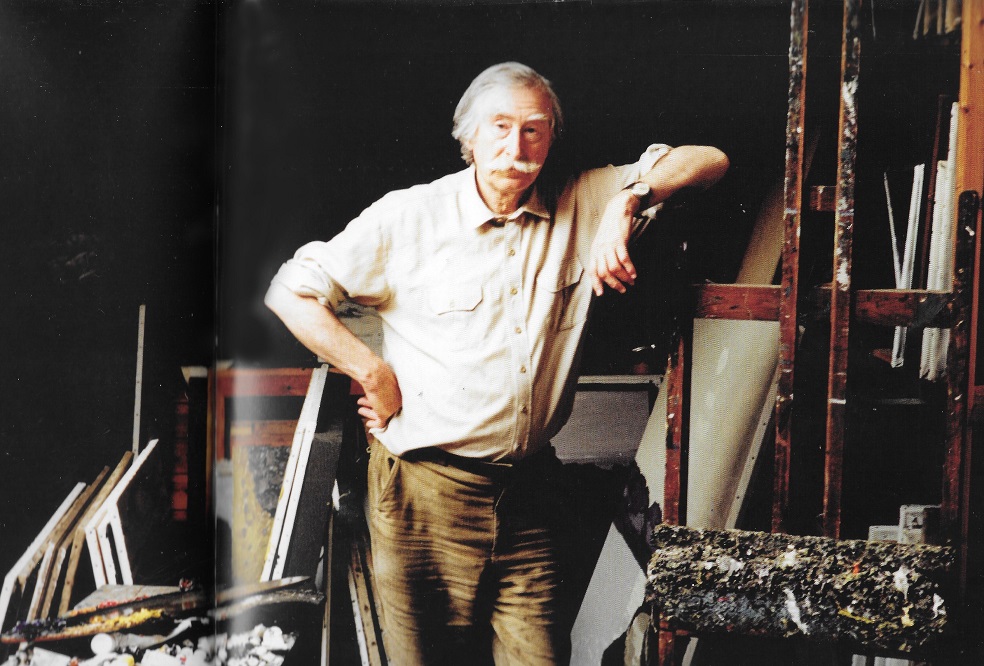

Settling on his image of Josef Herman he pauses and explains that he recently saw an image by Herman at an exhibition in Bristol, which depicted a family group in colours uncharacteristic of the refugee artist from Poland who eventually settled in Ystradgynlais: browns and ochres instead of his preference for reds and golds.

“But of course, all of Herman’s family, his mother and father, grandmothers and grandfathers, brothers and sisters all got gassed, and he was the only one to escape…

“I was really moved by it… the colours were all wrong for him, so it must have been about losing them I suppose…”

RS Thomas

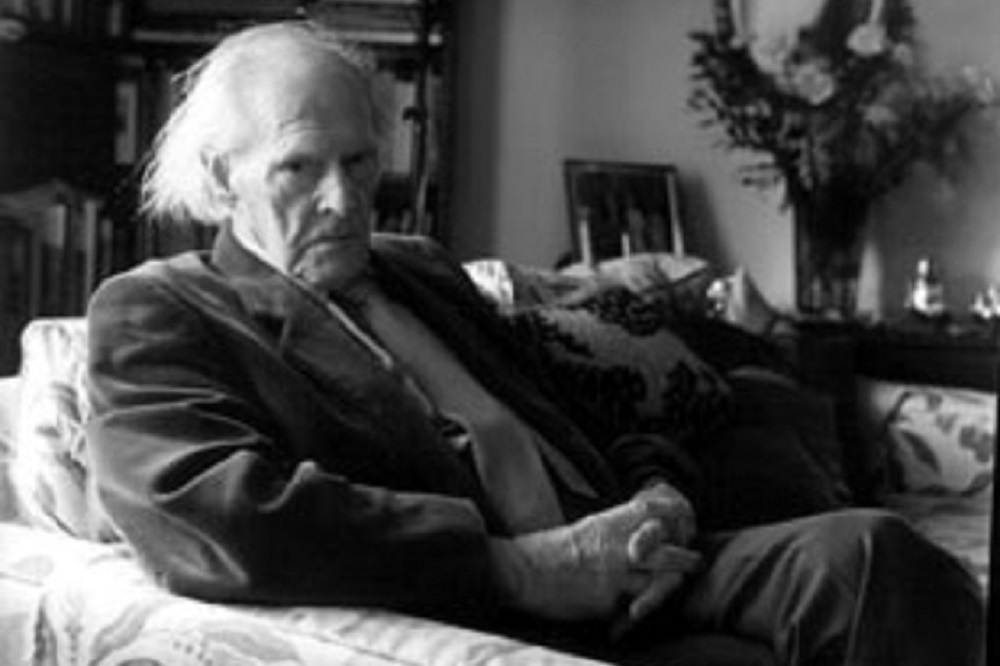

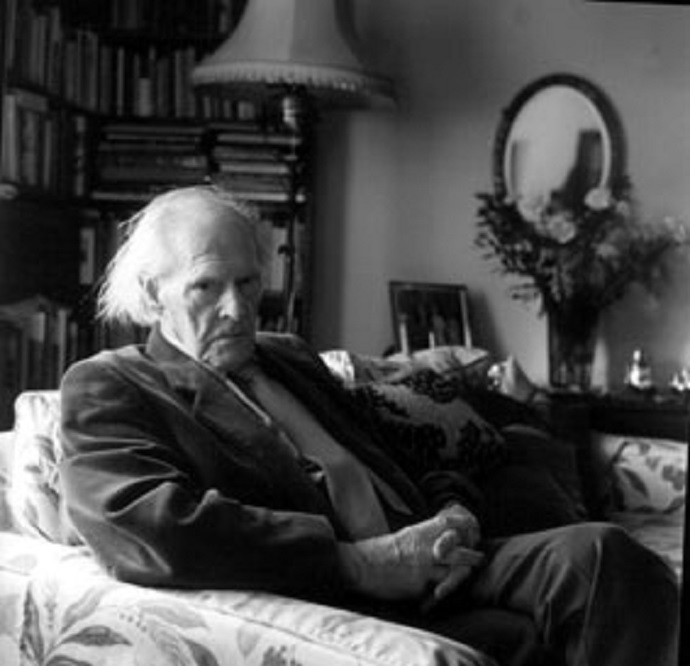

We land on the image of RS Thomas looking characteristically stern and down-mouthed. He was notoriously unwilling to sit for portraits and when Bernard was working for Planet magazine he asked his editor, John Barnie, to ask if the poet would be willing to sit for him.

“He said ‘Ask RS? Ask RS? You must be joking; I’m not asking RS anything. You’ll have to ask him yourself.’ So I rang him on a Monday or Tuesday and asked him and he said ‘Hmm, too busy this week, ring me Friday’…well I thought, that’s not a no, is it?

“So anyway, I went to see him and it was a very, very windy day, I didn’t take him outside at all, just a few shots inside because his hair would have blown away.

“Well, I thought, I can’t talk to him about poetry, I’m not qualified for that, so I asked him if he liked watching the rugby to which he said ‘Yes I watch it on the television.’ But I noticed he didn’t have a telly, so I said, ‘How do you watch it on the telly if you haven’t got a telly?’ He said ‘Ah, I borrow the neighbour’s.’

“I think he had a very dry sense of humour. I think what it was all about was that he didn’t want too much fuss. He was a vicar, but on the other hand he was also a very famous poet, probably one of the most famous apart from Dylan Thomas.

“One of the most famous poets ever to come out of Wales and I don’t think he wanted to know about all that…a false sense of modesty perhaps. I don’t know.”

‘Draw him quickly’

Bernard goes on to recount more anecdotes about RS and other portraiteurs. Peter Edwards, who Bernard describes as one of the best portrait artists in Wales, had already approached RS for a portrait and been refused.

On learning that he had since sat for a photograph, Edwards wrote to the poet a second time to ask again to paint him and was told “No, you wrote to me before and the answer was no, and the answer is still no.”

Turning to the image of the sculptor Ivor Roberts-Jones in his book, Bernard tells me, as a prelude to a further RS Thomas anecdote, that Ivor was the only man who could tell Kyffin Williams that something he had done was rubbish.

Kyffin had written to Bernard to say that the second wife of the reluctant sitter had commissioned him to take a portrait and asked his advice on how best to do it.

“Draw him quickly”, Bernard replied, going on to tell me that as RS wasn’t a particularly patient man, sitting for hours to be painted in oils would probably not work.

On a visit sometime later, Kyffin showed Bernard three pencil drawings from the sitting, two with a colour wash and one just a plain pencil head, which was the one selected to be exhibited at his retrospective at the National Library in Aberystwyth.

“I asked him ‘Have you done an oil’. Yes, in the studio still on the easel, was a wispy white haired R.S. painted with a pallet knife with battleship grey hair. What could I say? ‘Has his wife seen it’? Yes was his reply ‘she couldn’t stop laughing’. He was quite hurt, I think.”

Artistic heritage

The tales come thick and fast from this charming man who is utterly steeped in and part of the artistic heritage of Wales. Bernard’s collection is comprehensive and historically important.

He attended and photographed every writer who appeared at the Festival of Literature – the Dylan Thomas Festival and the Children’s Literature Festival which took place at the Dylan Thomas Centre for fifteen years.

He observes with regret and heavy criticism that the year-on-year cuts to the budget and the eventual sale of the centre was an act of what seems like cultural vandalism by Swansea Council.

“There is a piece in that Nigel Jenkin’s book where he wrote something about how we should protect the Dylan Thomas Centre, our centre … but it has gone on so that they managed to succeed in getting rid of it in the end. Swansea City Council have got a lot to answer for.

“The Dylan Thomas festival was a fine thing. But the other festival, the Children’s Book Festival was so important: it was the only dedicated festival for children’s literature; it encourage children to read… from all ages… right from junior schools through to secondary, and they invited all the top children’s writers.”

A jigsaw

“I could talk about this and these artists all day,” Bernard says with a sigh.

The images in his book number only 120 of the 1000+ he had to choose from.

“There were many I had to leave out, people who should have been in there.”

The body of work first came to life as a result of a short sponsorship by the Library of Wales, allowing Bernard to devote his career to it. Now it returns in its full glory back in the library’s archives.

It has been proposed that its digitalisation will become the happy task of a dedicated member of staff for a year, enabling the portraits which seem to get to the heart of their subject without flinch or fail.

Reflecting on this relationship with his subjects, Bernard writes on his website: “it is by relating the internal to the external that an image best expresses the essence of a person.

“The portraits operate at two levels: observation of individual – artists, writers and musicians – is at the same time an exploration of the proximities and distances between them.

“Each portrait is a self-contained art work, but when taken together the images amount to more than the sum of their parts.

“I saw them as Pieces of a Jigsaw which, seen as a whole, presents a portrait of the Welsh art world of the last decade of the twentieth century.”

Pieces of a Jigsaw is published by Parthian and is available here or from good bookshops

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.