Bernice Rubens (1923 – 2004)

On the centenary of her birth Desmond Clifford celebrates the writing and achievement of Wales’ greatest novelist Bernice Rubens.

In spite of winning the Booker Prize in 1970 Bernice Rubens was never truly embraced by Wales’s literary establishment. Or is it because she won the Booker Prize that she is held at a distance?

Cardiff-born Rubens conformed to several tropes of metropolitan literary elitism: the Booker Prize, literary north London, friendship with Beryl Bainbridge – all of which lay outside Welsh Literature’s protective cordon sanitaire.

Bernice was the first woman to win the Booker and, so far, and so conspicuously, the only Welsh winner. She beat entries by Iris Murdoch, William Trevor and Elizabeth Bowen, all of whom were established, if not towering, figures (and all three, as it happens, Irish; in 2023 there are four Irish authors on the Long-List, and no Welsh).

Bernice was a Cardiff and London contemporary and friend of poet and memoirist Danny Abse and both writers share their centenary this year. Abse is well-accepted in Wales’ literary Big Tent while Rubens seems to hover mysteriously near the awning.

Why might this be?

Accidentally Welsh

When Rubens says she was “accidentally” Welsh, this was true in the most literal way. Her father fled pogroms in Latvia and sailed from Hamburg apparently believing he was on his way to America.

Only when he discovered that Cardiff wasn’t Chicago did he realise he’d been cheated; even then the fleeing desperate were fair game. In Cardiff he met his wife Dorothy Cohen, whose family had fled Poland.

Murdered ancestors were left behind. Accidental, indeed.

Cardiff’a armpit

Bernice was born in Splott, “the unmentionable and indisputable armpit of Cardiff.” She attended the synagogue on Cathedral Rd, Cardiff’s most beautiful small building, and used today, somewhat bathetically, as serviced commercial offices. Her father’s tailoring business prospered and the family relocated to the posher Penylan.

Music was central to their lives and her two brothers and sister all played professionally at different times. Bernice played cello but to a lower standard. She noted, instead, that she learned how to listen, and this helped her develop as a writer.

She remained close to her family but described a heavy weight of parental expectation as a form of “abuse”.

First folly

She described reading English at Cardiff University as, “my first major folly…to be saturated in the great nineteenth-century tradition of the English novel turned out to be no great favour to a would-be writer.”

On graduation she became a teacher, which she enjoyed, in Birmingham, which she did not enjoy. After a few years she was sacked summarily, and extraordinarily, for organising opposition to the use of corporal punishment.

Moving to London she pursued a creative life as a writer and documentary film maker. She married Rudolf Nassauer, an aspirant novelist and wine merchant, whose family fled Germany just before the war. They had two daughters before the difficult marriage ended through his infidelity, though they maintained a lifelong relationship of sorts.

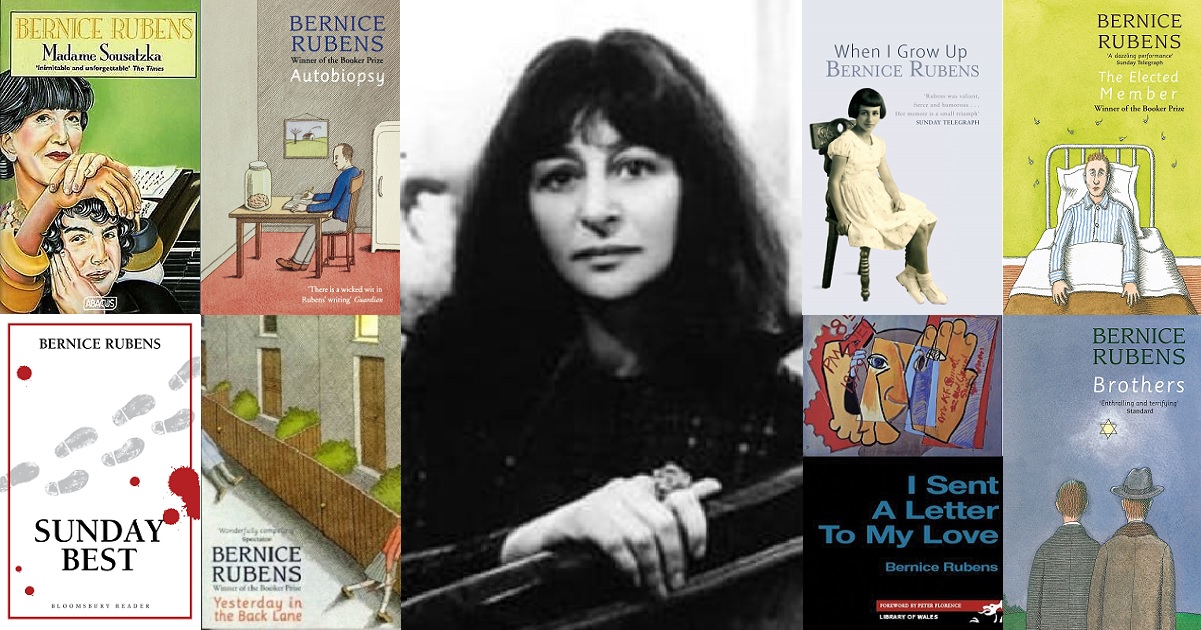

Rubens’ first novel, Set on Edge, was published in 1960. Her fifth novel, The Elected Member, won the Booker Prize (1970) and she was short-listed again in 1978 for A Five Year Sentence.

Madame Sousatzka (1962) and I Sent A Letter to My Love (1975) were made into films; Mr Wakefield’s Crusade (1985) was made into a TV drama by the BBC in 1992. Her memoir When I Grow Up (2005) has the dramatic flair of a novel.

Prolific

Well into her thirties before her first novel appeared, she was then remarkably prolific publishing at a rate of almost every 18 months, 26 novels in all. She rarely plotted stories in advance and suffered no writers’ block. Her imagination was inexhaustible.

In her lifetime she won acclaim and commercial success. Typically, her novels are short and easily readable. The setting is often domestic and suburban, emphasising the chill of her cold-eyed plots.

Yesterday in the Back Lane (1995) draws on her experience in wartime Cardiff against a background of German bombing and community shelter in a brothel near her home. I Sent A Letter To My Love (1975), a story of identity and sex, may be the only novel ever set primarily in Porthcawl.

Cross-dressing and sexual identity are themes in Mr Wakefield’s Crusade (1985) and Sunday Best (1971). In Birds of Prey (1981), two women are repeatedly raped by a ship’s steward and respond very differently to the experience.

Sweeping family history

Her 1983 novel The Brothers was markedly different from her other works. It is a sweeping family history (hers, of course) taking in Czarist Russia, Odessa, Hamburg, Cardiff, Leipzig, Moscow, Israel – and the Holocaust, where family histories ended.

The story is gripping but in parts almost too painful to read. One must imagine what it cost to write; in her memoir she hints only at difficulty, with heavy understatement. No Welsh author has written a greater novel.

Identity and ambiguity are central to Rubens’ work. The Jewish identity is characterised by movement, survival, the bag kept packed in the hall. The Welsh identity is marked by doubt and a certain lack of precision. Who, what and where, exactly? Does it include me, and on what terms?

In her memoir Rubens says, “my birthplace as well as my nationality were accidental, and I accepted that, by proxy, I was survivor.”

Druidical

She was Jewish and Welsh and didn’t describe herself as anything else. She remained a frequent visitor to Cardiff but had little sense of a Wales beyond; she envisaged the North in druidical terms. She was Cardiffian and identified with the city rather than the nation.

Her memoir is dismissive of the growing use of Welsh on public signage and she felt alienated by the rising national identity which developed over her lifetime, “Once upon a time, I had thought that the land was mine. But now I am made to feel a foreigner…”. Why she felt foreign isn’t rationalised and, today, this reflection feels rather sad and out of time.

No doubt her disobliging remarks about Welsh were poorly received by some and her negativity may have contributed to a certain wariness among those who arbitrate literary attention in Wales. In fairness, it is easier to embrace the willing and a larger heart is required to hug the recalcitrant.

Bernice Rubens is Wales’ greatest novelist, in either language, but remains strangely unclaimed and uncelebrated. No biography has appeared, no Writers of Wales monograph and there is little in the way of critical interest.

On literary grounds, this seems inexplicable and now, as we celebrate her centenary, is the time to embrace her whole-heartedly. Above all, and the accolade which matters above all others, she deserves to be read.

Recommended reading

Maybe start with her Booker Prize winner The Elected Member (1969); it’s still in print and most likely to be in bookshops.

Highly recommended: Madame Sousatzka (1962); Sunday Best (1971); I Sent A Letter To My Love (1975) and Yesterday In The Back Lane (1995).

Her masterpiece is The Brothers (1983), a long historical novel stretching from Odessa to Butetown. As they say on TV these days, you may find some of the content distressing; your reward is perhaps Wales’s greatest novel.

For the very interested, her memoir When I Grow Up (2005) is a riveting and dramatic read.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Bernice Rubens was a student of City of Cardiff High School for Girls when it was on The Parade. When I was there, in second 11Plus class that started in 1948, we heard about her. She had been a student of Miss Catherine Carr, a brilliant English teacher