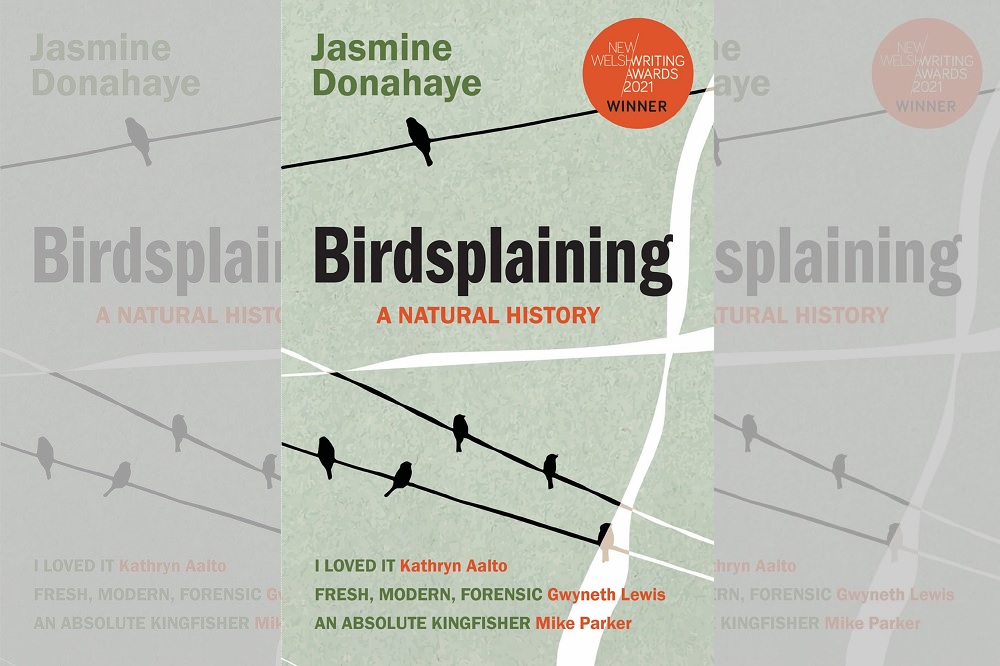

Birdsplaining

Meetings at Dusk

Jasmine Donahaye

The following is two excerpts from the essay ‘Meetings at Dusk’ in Birdsplaining: a Natural History. Here the author recounts visiting Cross Inn Forest to look for nightjars.

Round the bend came the human inconvenience: a boy running ahead, about eight or nine, whacking with a stick at the willowherb beside the path. When he spotted me, he stopped, looked round at his parents, and hurried back to them. They glanced at me, and then they looked at one another, and then they didn’t look at me again. The Jack Russell behind them hadn’t yet noticed me, and the woman stopped and picked it up, and then it began to growl.

As I drew near, I wished them ‘Noswaith dda’, but they didn’t answer. The boy stared at me, but his parents looked rigidly past me into the darkening distance ahead of them. The dog’s steady growl increased as I approached, and it turned its head and watched me walking past, growling all the while.

I heard their footsteps moving away behind me, and when they reached the next bend, one of them began to talk again, but I couldn’t make out what they were saying, and then they were round the curve and there was no longer any sign of them. But they’d left behind them their crackling hostility, unspoken but tangible, and with it the wound of loneliness when you are placed outside a human bond.

All my thought of nightjars was gone; all thought of birds, all awareness of the evening chorus around me had been erased by their hostility. It could have been any number of things, I told myself; it was not necessarily what I thought it was. Don’t jump to conclusions, my little inner voice said – you can’t know, though I thought I did know.

I wish I was never self-conscious like that, never had to second-guess myself, never had to try to convince myself, as I tried to do then, that I was imagining something. I wish it were possible to walk somewhere rural or wild, and not be braced against the ever-present possibility of hostility.

But it doesn’t go away, early experience – and my early experience taught me that to be brown in a rural place is to be asked implicitly or explicitly what you’re doing there, to give an account of where you’re from, to be told you don’t belong. In Britain, if you’re brown in a rural place, you’re always seen as being from somewhere else.

Of course you can’t opt into what’s indigenous. You might identify with it, but you can’t claim it as yours if you’re not from there. There is a shadow root of beget in the word indigenous, as though the land itself begets you. Indigenous, native: both mean ‘natural’ etymologically and semantically, but though natural, like native, may have its roots in nasci, to be born, being born in a place isn’t sufficient to make you indigenous; it cannot make you innate.

Immigrants can only be indigenous to the place they emigrated from; the second and subsequent generations aren’t indigenous to anywhere. Without family roots in the place you’re born, you always carry the taint of being an introduced species. You might adopt a cultural tradition, a particular relationship to a specific place, a specific land, but they’re not really ever yours, not authentically.

That is how you’re seen, even if it’s not how you feel. And others’ perceptions about your family’s origins shape how you feel about where you are, even if your family’s origins did not do so in the first place. Where are you from, they ask. No, but where’s your family from – where are you from originally? Because if you’re brown in rural England, in rural Wales, you’re always from elsewhere.

Indigenous is a neutral descriptor only if it refers to an oppressed minority; it’s hostile and exclusive if it refers to an oppressive majority. ‘The indigenous British’, ‘the indigenous English’, ‘the indigenous Welsh’, ‘the indigenous language of the British Isles’ – if I hear or read those terms, I wince.

With the exception of citing Welsh as an indigenous language in order to challenge the ‘speak English’ xenophobia directed at migrants, I know what identity group and accompanying set of attitudes is usually being evoked, consciously or otherwise: white, anti-immigrant, nativist, ruralist, fascist.

The distinction between some notional indigenous population and those who are not ‘from’ here operates implicitly in rural places throughout the UK, no matter how many people of colour are included in broadcast dramas set in Pembrokeshire or Cumbria, in Ceredigion or the fictional public service announcement county of The Archers.

If you’re brown in Ambridge or Aberystwyth, the presumption is that you’re from somewhere else (Where are you from? No, where are you from originally, I mean where are your parents from?) and this, therefore, becomes your own internalised reality too.

Which is part of why, if you’re brown in a white space, you are always checking for signs, preparing for the challenge, steeling yourself against the reaction that suggests you don’t belong, that states implicitly, and often explicitly, that you are not a part of, but apart from.

And it’s partly why, in the absence of interfering human meanings in a wild place, the whole question of belonging or not belonging, being part of or apart from, can fade for a while into nothingness.

What did this couple at Cross Inn Forest mean, with their cold, looking-away silence? Perhaps they had been in the middle of an argument; perhaps they were socially awkward; perhaps they never spoke to anyone they met while out walking their dog. I couldn’t know. All I could know was how it affected me. In rather typically British style, nothing had been said, but nevertheless a great deal had been said. Confirmation bias, someone might say – and yes, it’s true: early experience readied me for hostility, and subsequent experience reinforced it.

But there are also challenges to my biases. One hot July day, when I went for a run along the narrow road towards Swyddffynnon, I was already primed for a confrontation with a driver.

The banks were overgrown, with nettles and heavy seed-heads weighing down the long grass, which narrowed the already narrow road, leaving no room for a car and a pedestrian to safely pass one another.

It was a sultry day, humid and overcast. The still air was thick with low-flying insects, and swallows were skimming near the ground and along the softening tarmac. I’d run three miles, and I was sweating heavily, when a car, coming towards me, pulled to the side and stopped. It had an English plate; I assumed it was driven by a tourist.

As I drew close, the driver, a heavy, middle-aged balding white man shouted from the open window, ‘You ain’t right!’ in a London accent. Was this just hostility for presuming to use the road and annoyingly slow him down, or was it going to be something worse? ‘What do you mean I’m not right?’ I asked, slowing as I passed, and then running backwards, registering how, defensively, unconsciously, I had poshed up what he’d asked. Was he going to react to that too? ‘Runnin,’ he shouted. ‘Runnin’ – and he shook his head with pity, making a wide gesture that took in the heat, the hill he’d just come down, the whole hot hostile world outside his safe cool car.

In the darkening forestry, the Smidge was starting to lose its strength, or the insects were worse: they weren’t landing, but they were making contact. I got as far as the open land where the track reaches a T-junction, and then turned back, ill at ease. There were no nightjars. A late and annoyingly loud song thrush on a high branch at the edge of the uncut trees was repeating and repeating, blocking out quieter sounds.

There were smaller, unidentifiable calls, the repeated quiet tzeep-tzeep of young birds, a snatch of robin song. Then on the heathland a grasshopper warbler started up and that was almost as good as what I’d hoped to hear. If it had not been for that human encounter I might not have walked that far, and might not have heard the warbler.

But on my way back, the nightjars began.

Unheimlich, I thought, afterwards – reaching for a word that has no strict equivalent in English: eerie, uncanny, but really meaning the familiar made other. Everything about heimlich undone, in both of its original meanings: homely, comfortable, known, but also hidden, secret, private. So that in Freud’s exploration of the word and of the literary depiction of the uncanny, unheimlich is the undoing of both those meanings: the familiar made other, and what should be hidden (from consciousness, at least) revealed.

That’s what the nightjar did to me: it revealed something about the hidden space that is the wild world at twilight, that strange transitional time when mystical transformations occur in folklore and myth. But at midsummer, when it never gets fully dark, twilight is not a transition but a state, and the nightjar’s eerie continuous churring, a multi-directional, unlocateable sound, was its aural expression.

I wondered whether that was what the couple had experienced when they’d seen me – perhaps I had made their world unheimlich, in the way that their response made the world unheimlich for me. Perhaps that’s what an encounter with the Other always does. It makes the familiar unfamiliar, and reveals what is usually hidden: the tenuousness of your feeling at home in the world.

Birdsplaining by Jasmine Donahaye is published by New Welsh Review. You can buy it from all good bookshops or you can buy a copy here.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Glad to read your excellent writing. I could tell many of my experiences. I sum it up concisely: I am not racist. I am more comfortable with some cultures as opposed to other, less pleasant cultures. There are people across all behavioral points of humanity. I try to be pleasant to all.