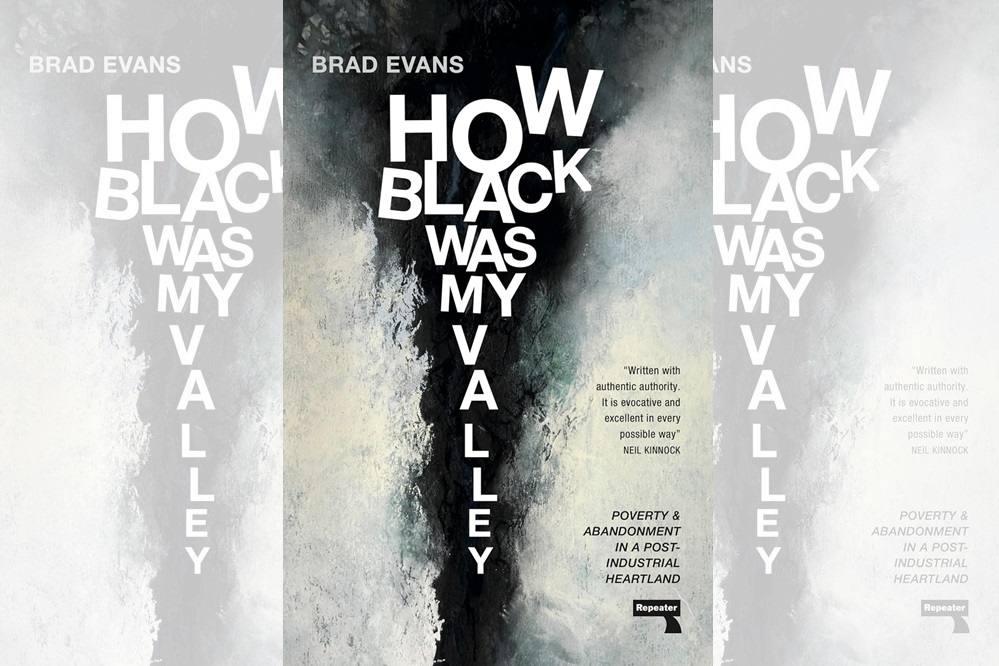

Book extract: How Black Was My Valley by Brad Evans

We are pleased to publish an extract from a new book described as an ‘honest portrayal of post-industrial communities ravaged by decades of abandonment, How Black Was My Valley is the story of lives defined by poverty, catastrophe and the fading dreams of better futures.’

Brad Evans

A black Klondike was born in the valleys of South Wales, as it was in Appalachia and elsewhere where the mining took hold.

Many might have even found a home in those mountainous regions of Kentucky, born of their own continental drifts, volcanic explosions and platinic collisions, finding sympathy with one another as they looked into the burning embers.

Poverty invokes a geography of its own, cragged, worn and marked by its unique measures of depth. It is also shaped by the fates of hostile ecologies, geologies of hardship, which too often translates into the character of community life.

Villages around the world have been rooted into where the black could be found. It was the foundational stone of where many people would permanently reside.

Bellowing earth

Territories then were discovered by the appearance of a colour, more natural than any which bleeds from flags adorning the map.

If there was a flag to be flown in places like the Rhondda, it would be made of the smouldering black clouds that billowed out across the horizon from a thousand towering poles.

Smoke pennants of allegiance raised to announce an age marked by the sovereignty of the stone, under which marching men fought.

The fiery red would come later as the bellowing earth inevitably caught alight in the changing winds. A colour worn as much as the tragedy cloaking these towns — overdyed with the hint of a tragic procession whose congregations lived so close to death.

A colour of mourning drawn from the intractable earth; but nonconforming all the same.

Timid canary

Yet everything would be guided by the light in this wilderness; at least that’s what the lyrics to John Hughes’ “Cwm Rhondda” had us believe, as a nation would soon find solace singing of its bread from heaven.

Without the light, the miners would have surely perished as too much time in the abyss would fully consume their minds through its own depression sickness. Candles were lifelines. And the only other vibrant sign of colour — the timid canary — were caged as messengers of impending disaster that emerged from shadows in the densely compacted air.

How could so much be wagered on the importance of the naked flame? Then again, how could it be any other way?

Deep scars

The flame wasn’t just about survival, it lived and breathed the ambitions of these men, and the meagre hopes that were dug out in the cavernous depths beneath their homes.

The flame guided through the impenetrable darkness; yet its poetry and mission always carried the darkness along, for it was the black setting that gave the flame its most meaningful purpose and clarion calling.

So deeper and deeper the flame was carried, opening onto caves of extraction, and producing dark silhouettes upon the pit’s black walls, which only those with adjusted eyes could properly detect.

There was an artistry to the dancing movements of these dark shadows, who were completely dependent on the trust of companions, and the flame whose extinction would point to a tragedy too difficult to bear.

In the long hours of the dark, the blood and sweat was mixed with the dusty tears, which in turn cast its own shadow on the floors for the select few to see as it burnt away. And hands spoke of their own unforgiving bruises, their lines revealing traces of the fragmented scars that cut so deep they blackened the soul.

It wouldn’t take too much of a reader to decipher these simian etchings telling of hardship, suffering, defiance. Silted signs of ancestors whose tempter and desire were a testimony to the cold black conditions, which may only be forgotten in name.

Manliness

Every day John would have walked past the towering black mountains. They were not just an integral part of the landscape. They were defining.

But he would have been under no illusions about their content and character. Might he have even looked upon them with pride? A visible symbol of his manliness and a clear indication of the transference of his labour?

Certainly, the only environmental concern held was to ensure he lived another day. Thereafter, he wished to return from his arduous work with all his working muscles and bones intact. Nobody needed a broken miner.

And nobody cared what damage the blackness might have been causing. Breathe until tomorrow. Let the heart beat enough to prise the blackness away.

John might also have marvelled at the way the mountains seemed to take on a life of their own. How they revealed deep cut paths in their surface, how those paths became deeper and wider when the rains fell, and how they would on occasions simply disappear from sight.

The black mountains of the valleys became the image so often associated with its minerally abundant and yet sorrowful reality. Year later, they would become associated with a tragedy so devastating, it still casts its fateful shadow more permanent than any weather system.

For what we called “the mountains” were no mountains at all. They were not the black mountains of the east in Powys and Monmouthshire, made of stubborn old sandstone, which stood so defiant in the face of the ice.

They were moving waste dumps for all that was disposable, thrown out for all to look upon and nobody to see.

How Black Was My Valley: Poverty and Abandonment in a Post-Industrial Heartland by Brad Evans is published by Repeater Books. It is available from all good bookshops.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.