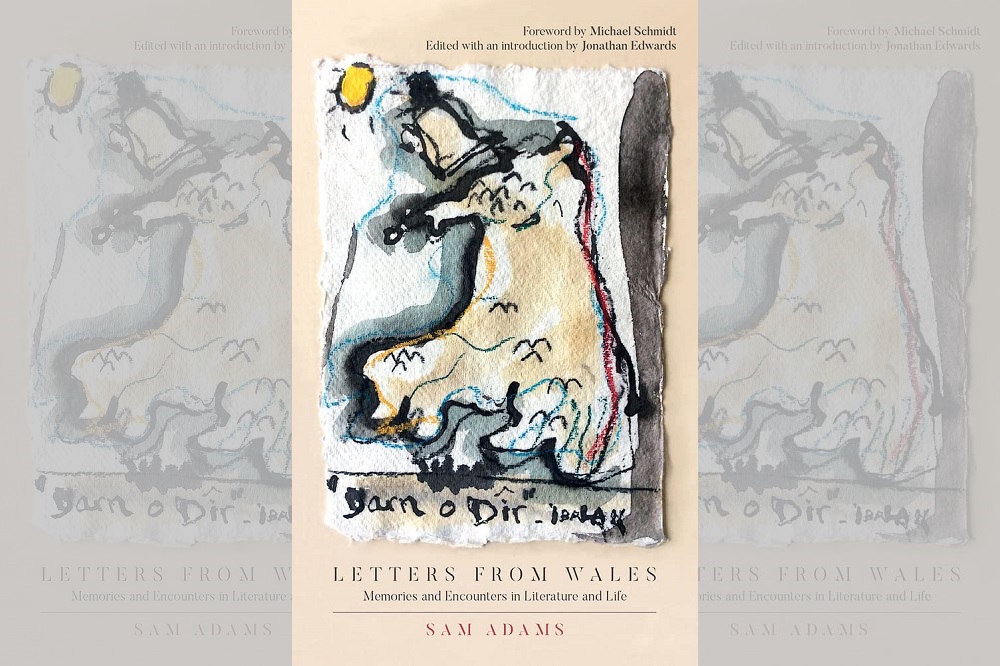

Book extract: Letters from Wales – Memories and Encounters in Literature and Life by Sam Adams

The newly released list of the influential 2023 Granta Twenty Best Young Novelists includes Thomas Morris from Caerphilly. His young talent was apparent when he won the English language Wales Book of the Year award in 2016 for his collection of short stories We Don’t Know What We’re Doing.

Here is an account of the collection taken from Sam Adams’ forthcoming and monumental Letters from Wales: Memories and Encounters in Literature and Life, a case of one of the most senior figures in Welsh letters appreciating the ability of new writers coming through.

WALES BOOK OF THE YEAR 2016

September 2016

Sam Adams

Just a week ago, early evening, we set out for Merthyr Tydfil. The A470, that joke of a trunk road running from Cardiff almost two hundred miles to Llandudno, is dualled at least as far as Merthyr and, the crawl of commuter traffic over for the day, we made good progress to the gates of the town. Then things went badly awry.

After a while of blundering into cul-de-sacs and halting, baffled, at No Entries, we saw a sign to Twynyrodyn. It was the memory of a fine poem, ‘Ponies Twynyrodyn’, that prompted me to point the car that way. At once we found ourselves on a steep hill, heading north, out of town. We stopped and asked directions. Discussion ensued about a number of options.

The simplest appeared to be to keep going until we reached a roundabout at the top and there turn left. After that advice the road continued, if anything more steeply, up. No wonder the ponies in my old friend’s poem came down that way in winter: the top is at the very edge of the Brecon Beacons.

But our advisers were wise indeed, the left turn brought us steeply down and precisely to our destination – the Red House, Merthyr’s old Town Hall, restored, in part with European Development Fund money, and re-opened on 1 March 2014 as a ‘creative industries centre’.

This was the venue for Wales Book of the Year 2016. In recent years these events have alternated between Cardiff and Caernarfon; bringing it to Merthyr has underlined a sense of inclusivity in the arts in Wales that has long been an aspiration of Literature Wales and the Arts Council.

The evening was remarkable for revealing two triple prize-winners. Caryl Lewis swept the board in the Welsh language: her novel Y Bwthyn (The Cottage), published by Y Lolfa, won the People’s Choice Award (online voting), the fiction prize, and the overall Book of the Year Prize. And Thomas Morris did the same in English with his collection of short stories We Don’t Know What We’re Doing (Faber).

Poetry

Philip Gross won the Roland Mathias Prize for poetry with Love Songs of Carbon (Bloodaxe), his eighteenth collection. The poems reflect the experience of a Cornishman long resident in Wales. In Cornwall there are strong ties, vibrant still in memory, with loved parents; in coastal south Wales, the living connection of married love.

The collection is dominated by Time (as are we all), and persistence is the message echoed from poem to poem. Art can, or must, persist against all odds, as in ‘Paul Klee: the late style’.

In ‘Thirty Feet Under’, the hermit crab and sea anemone on the foreshore, exposed by the retreat of the huge Severn estuary tide, convey the same message: love must go on regardless of statistical evidence. ‘Coming of Age’ sees us propelled willy-nilly through life’s stages, and still what matters in the end is love.

‘Watermark’, that ‘line in the sea made of nothing’, where gulls gather to feed, and ‘Several Shades of Ellipses’ are multifaceted images of love continuing to the ultimate full-stop.

Gross’s poetry has acute observation of the natural world and human relations, and phrase-making that often stops the reader in his tracks. It is both profoundly serious and, on occasion, playful, and always alert to the fresh perspectives on life afforded by science and technology.

In ‘Mattins’ it wrestles with the imponderables of faith and the human condition in a way that Roland Mathias, whose name is preserved in the prize he received, would recognise at once as akin to his own precarious knowledge of uncertainty.

Unique character

The prize in the English-language fiction category was for the first time sponsored by the Rhys Davies Trust. It was peculiarly appropriate that it went to a short story collection, for Rhys Davies was, and is, an acknowledged master of the genre.

The setting of Thomas Morris’s stories is the town of Caerphilly, dominated by its colossal Norman castle and the mountains beyond. True, one story takes its cast of young men on a stag-do to Dublin, and another takes the town into some future or parallel time, but all are permeated with its unique character and nearly all with recognisable localities.

Although he has studied and lived in Dublin for the last eleven years, Caerphilly remains Morris’s home. He can recreate it wherever he happens to be, much as Joyce carried Dublin around with him and drew upon his memory of it constantly.

Like Joyce again, his vision is clarified by being away from the inspirational place. Even if not quite to Joyce’s capacity to entertain and confound the reader, there is enough variety in Morris’s approach to storytelling – first, second and third person narratives, past, continuous present, even future tense – to interest a creative writing class.

Contemporary South Wales

The voices Joyce heard in exile were Dublin voices, and the language of Morris’s stories is a version of the contemporary south Wales demotic. It lends itself readily to hyperbole and humour.

Things rarely go well for the characters, and they are frequently afflicted by the manifold ‘issues’ of modern life, but humour is never far away from the troubling surface of events. With one exception, ‘Strange Traffic’, which concerns a pensioner couple, the stories involve men and women in their twenties, often the late twenties.

They are people who are lonely, depressed, pinworm-infected, self-harming, drunk, hungover, aimless. That is, people who should ‘know what they are doing’, but do not. The stresses of life and mental fragility in situations where the old, fundamental certainties and expectations – work and a wage, and secure, lasting relationships – no longer obtain are themes that run through the book.

In an interview, Morris has said he is interested in ‘the idea of adulthood […] the lines between being a boy and a man’. He identifies the distinguishing feature of adulthood as being given ‘genuine responsibility’.

Here he has hit upon one of the important factors influencing the nature of society in post-industrial south Wales, and probably wider afield. In the harsh environment of the pits and steelworks, adulthood came early, as men still in their teens took on daily and lifetime responsibility for themselves and their fellows. Such was the nature of the work.

Today, employment, where it is available, is usually physically safe, often highly individualised, and too often temporary. If this does produce men – and women – who grow older without becoming adult, it is a problem for society and we are a long way from a solution.

Engrossing

For all their underlying seriousness, the stories are constantly engrossing and shimmer with memorable images: ‘smiling like a bag of chips’, ‘pale and thin, like semi-skimmed milk’, ‘street lamps glowing like electric lunch boxes’, ‘her mother was still percolating after her father’s death’.

In Dublin, Morris edited Dubliners 100 (Tramp Press, 2014), an anthology of short stories to celebrate the centenary of the publication of Joyce’s Dubliners. He is editor of the literary magazine The Stinging Fly, which encourages new writers. I’m afraid he was a new writer to me; we shall, I’m sure, hear more of him.

PN Review 231, Volume 43 Number 1, September – October 2016.

An extract from Letters from Wales: Memories and Encounters in Literature and Life by Sam Adams, out now in hardback through Parthian Books (£20) and available from all good bookshops.

Thomas Morris has been selected as one of the 2023 Granta Twenty Best Young British Novelists. His second book of stories, Open Up, will be published by Faber this August.

Sam Adams was born, in 1934, and raised in the small mining valley of Gilfach Goch, when it still possessed three working pits. In common with most of the valley’s children at that time, his father and grandfathers were mineworkers.

He was educated at a local primary school, Tonyrefail Grammar School and the University College of Wales, Aberystwyth, where he studied English. He began writing in the corners of a busy working life in the education service, emerging first as a poet.

His work appeared in all the Anglo-Welsh magazines and he became successively reviews editor then editor of Poetry Wales. For the University of Wales Press he has written three monographs in the ‘Writers of Wales’ series, on Geraint Goodwin, T J Llewelyn Prichard and Roland Mathias, and edited Mathias’s Collected Poems and Collected Short Stories.

His three novels Prichard’s Nose, In the Vale, and The Road to Zarauz have attracted critical praise, as has Where the Stream Ran Red, an amalgam of family and local history.

His connection with Manchester-based Carcanet began in 1974 when he edited Ten Anglo-Welsh Poets for the press. Since 1982 he has made more than 150 contributions to its magazine PN Review.

Forthcoming Events:

Sam Adams will be in conversation with Dai Smith and Emma Schofield at Hay Festival on Friday 2 June 2023, 2.30pm.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.