Book extract part 2: Letters from Wales on ‘Y Wladfa’ and ‘Tryweryn’

Sam Adams

We are pleased to be publishing a selection of letters from the newly published volume by Sam Adams which gathers together some of his columns for the poetry magazine PN Review. Here Sam commemorates the establishment of Y Wladfa in Patagonia.

I seem to be remarking significant anniversaries of writers and events with increasing frequency: no doubt a consequence of growing older. The year 2015, now ending, has two that are highly significant in the annals of Wales.

They are instantly recognisable to anyone with a superficial knowledge of modern Welsh history by the identifying names: ‘Y Wladfa’ and ‘Tryweryn’.

Settlers

Y Wladfa (The Colony) is the name given to the one hundred square miles of Patagonia granted to Welsh settlers by the Argentine government. We have been celebrating the 150th anniversary of the their landfall at what is now Puerto Madryn on 28th July 1865. ‘A cold coming [they] had of it’, the depths of the southern hemisphere winter, and a barren shore.

It is even now a remote territory eight thousand miles from home, nine-hundred south of Buenos Aires. They found it sparsely populated by Tehuelche hunter-gatherers who, after initial suspicion, decided to be friendly and helped to sustain them in the first terrible years.

Certainly, it was nothing like the land promised in the glowing report brought back by Lewis Jones and Capt. T. Love Jones-Parry, sent out to reconnoitre and assess in 1862.

Customs

The name of Michael D. Jones (1822-98), a Congregational minister and fervent nationalist, born near Bala, north Wales, is the most prominent connected with the venture. Ordained at the Welsh church in Cincinnati in 1847, he hoped life in America, beyond the influence of England, would allow the many immigrants from Wales to hold firm to their language and customs, but soon saw this could not be.

Supported by like-minded individuals and groups scattered across America, he sought other locations where a new Welsh colony might be established, and Argentina, where the government was keen to populate empty land in the south to forestall encroachment from Chile, offered the best prospect.

At public meetings up and down Wales the promise of a hundred acres each of land in the Chubut valley attracted individuals and families. Eventually, 153 (a third of them children) sailed in a small converted tea-clipper, the Mimosa, out of Liverpool, where much of the committee work behind the venture had taken place.

The hopeful emigrants included preachers, a schoolmaster, one builder, two farmers, one ‘doctor’, miners and quarrymen. Three-fifths were from the industrial valleys of south Wales, accustomed to heavy labour and hardship, though not of the sort they encountered in semi-desert at 43 degrees south, between the Andes and the sea.

Even if they had all been experienced farmers, it was too late to plant for next year’s crops. Sheep and cattle herded overland for them were stolen en route, food and water were in short supply: it began to look like Chesapeake 1609. Some left in despair, and there were many deaths, especially among the children, but the colony survived.

Minority language

Within a couple of years, an irrigation project, the first in Argentina, inspired by Rachel Jenkins, a farmer’s wife, began the creation of fertile wheat lands either side of the Chubut river, and the remaining immigrants were confident enough to explore farther inland and extend the colony to a fertile valley in the foothills of the Andes.

Fresh waves, wavelets rather, of Welsh immigrants, 500 or so in all, arrived within the next decade. By 1875 the new Wales that Michael D. Jones had dreamed of, where Welsh was the language of everyday life, of law and administration, education and religious observance, and every man and woman over eighteen had the vote, existed indeed.

It couldn’t last. The government in Buenos Aires, determined to assert its authority, insisted military conscription applied equally to the young men of Y Wladfa. In 1896 it declared that all education was to be through the medium of Spanish. Then the economic success of the colony contributed to its undoing: immigrants from Spain, Chile and Italy poured in, until Welsh became once more a minority language.

About 50,000 Patagonians can claim Welsh ancestry; estimates of the number of Welsh-speakers in 2015 vary from 1500 to (a very optimistic) 5000.

Today, there are regular cultural exchanges between Wales and Y Wladfa. Each year three language development officers from Wales spend from March to December in Patagonia promoting Welsh language learning for children and adults.

The number of people pursuing Welsh courses rises year by year (985 in 2013) and a Welsh-medium primary school has been established. As in Wales, through education, a new foundation is being laid that should preserve the language for at least another generation.

About nine miles south of Aberystwyth on the A487, outside the village of Llanrhystyd, you see a prominent graffito, over-painted red now, on what remains of a stone wall : ‘Cofiwch Dryweryn’.

As he tells us in his lively autobiography, My Shoulder to the Wheel (Y Lolfa, 2015), it was originally daubed in white by Meic Stephens in 1962/3, when he and a friend, ‘went out into the night to paint [Nationalist] slogans on public buildings’.

He was then a young schoolteacher and it was a risky business, not least because of the interest the police and MI5 took in what was construed as anti-establishment activity of any kind.

This simple dictum, ‘Cofiwch Dryweryn’ (Remember Tryweryn) has achieved iconic status surpassing any effort by Banksy. It has become part of our national consciousness.

Protest

In 1957, an Act of Parliament gave Liverpool Corporation the right to dam the River Tryweryn in north Wales, and so drown the village of Capel Celyn and surrounding farms and farmland. The area was entirely Welsh-speaking. All but one of the thirty-six Welsh MPs voted against the Bill, but it made no difference.

Immediate and widespread public protest was similarly ignored. People of Capel Celyn, men, women and children, parading through Liverpool to attend a meeting of the corporation, were vilified and spat upon. From 1960 to 1965, during the construction of the dam, protest continued and intensified.

Two sabotage attacks delayed the work, though not for long, and those responsible were arrested and tried; two were imprisoned. At the official opening of the dam on 21 October 1965, a large crowd drawn from all over Wales were in no mood to celebrate.

Protesters who lay in the path of the cavalcade of visiting dignitaries and escorting motor-cycle police were dragged away. Alderman Sefton reached the podium to begin a planned forty-five minute ceremony. Pandemonium ensued; microphone wires were cut, stones were thrown, scuffles broke out. The event was abandoned – but the dam was there and the Welsh-speaking community erased.

Colonial

Tryweryn was a late example of colonial exploitation. Wales as a country was defenceless against the expropriation of its land and resource by a single English authority. The city’s argument that its need for drinking water gave it an overwhelming prerogative does not stand examination.

In a recent television broadcast Lord Elystan Morgan, who as a young lawyer defended the Welsh saboteurs, said the water Liverpool took (and still takes) without payment was sold on as industrial water to twenty-four other English authorities.

The historian, Wyn Thomas, argues that 1965 was a turning point for Wales and that successive Welsh Language Acts and the establishment of a National Assembly have flowed from the humiliation of Tryweryn.

But the language is still under threat, not least because a minority of the population here have no love for it and, with a few honourable exceptions (J R R Tolkien comes at once to mind), no-one in England cares a jot.

If this is still a United Kingdom, as is alleged, politicians, television, radio and newspapers should play their part in educating the British public at large about the Welsh language, and inspire all with the desire to preserve it.

As things stand, the disdainful indifference of Westminster governments and the metropolitan media to the fate of one of the precious ornaments of European culture, with a literature older than English, remains persistent and damnable.

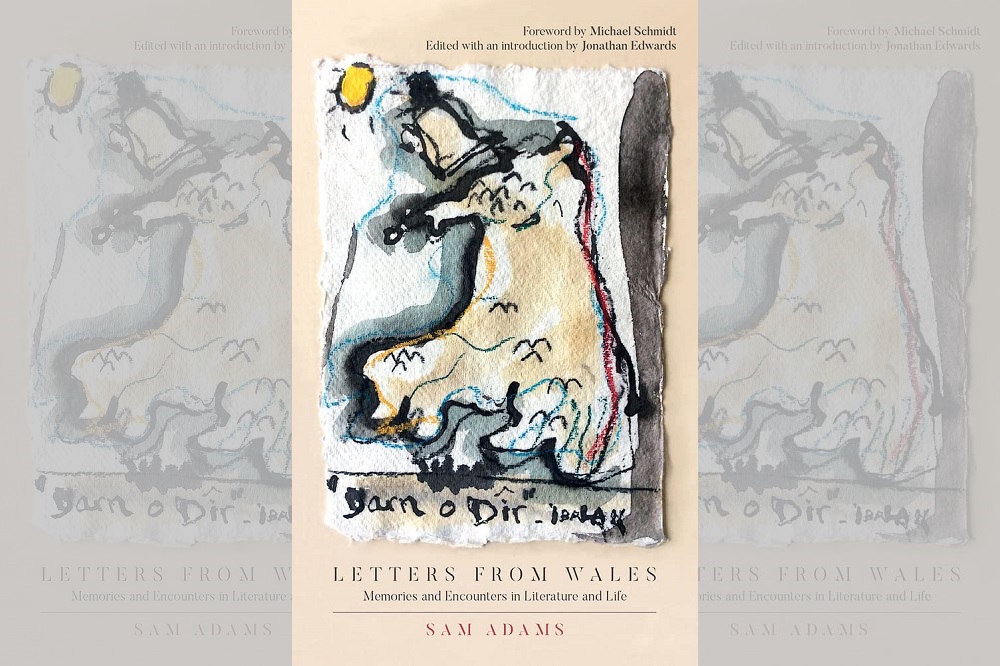

An extract from Letters from Wales: Memories and Encounters in Literature and Life by Sam Adams, out now in hardback through Parthian Books (£20) and available from all good bookshops.

Forthcoming Events:

Sam Adams will be in conversation with Dai Smith and Emma Schofield at Hay Festival on Friday 2 June 2023, 2.30pm.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.