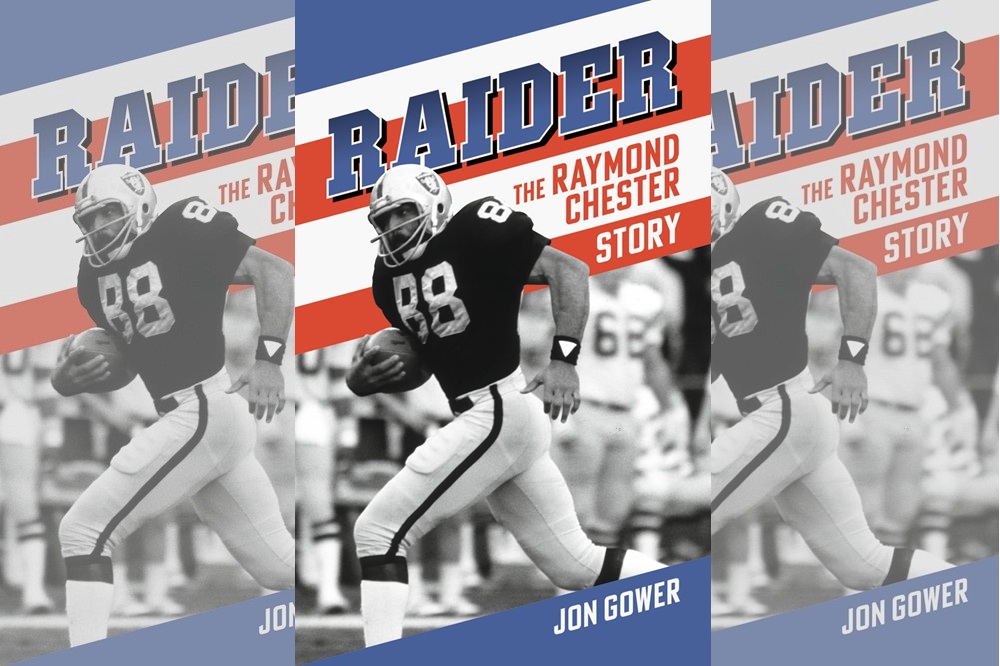

Book review: Raider: the Raymond Chester Story by Jon Gower

Desmond Clifford

Raymond Chester was an American footballer in the 1960s/70s. The sport has become progressively more familiar to us during recent decades through television and sell out NFL matches in London. It has a popular, if not fanatical, following in this country.

I’m not one of them, but I have friends who will stay up all night to watch critical games live from America.

Welsh rugby has lost Louis Rees-Zammit to the NFL dream and this, too, has stirred some interest.

The essential objective of American football, like its cousin, rugby – a sport of Talmudic complexity – is to get the ball over the line or between the posts for points. The other team tries to stop you, so ‘offence’ and ‘defence’.

The players are extremely large and fast and wear padding and helmets for protection.

Supple, partisan cheerleaders marshall pompoms decorously and shout motivational encouragement throughout the game.

The half-time Super Bowl performance – Beyoncé, Kendrick Lamar, Snoop Dogg and the like – creates the most expensive advertising slot on the planet.

I have family connections with Boston so default to the New England Patriots – like Manchester United, a charmless utility team for people who don’t really know the sport.

If you like American football, you’ll appreciate this book in any case. If you don’t, it’s worth knowing that it’s about much more than football.

Character

The story of Raymond Chester is about character, self-belief and perseverance.

It’s about Black America, social change and the role of sport in shaping individuals and society, building identity and self-esteem.

The industries which did most, and earliest, to promote racial integration are those based on objective talent – sport foremost among them but also music and entertainment.

Corporate life lags way behind.

A little context will help. Prolific author Jon Gower is, of course, Welsh. His wife is American, and her sister is the partner of Raymond Chester, that’s the connection in what might otherwise feel like a random topic for a Welsh author.

JG has spent significant time in America and is particularly interested in its culture and literature (outrageously, he throws away a line that he once spent a day with John Updike; there’s another book all by itself!).

The story captured by JG is accidental, in the best sense, and would not have been written but for the random encounters of a Welshman with a pen.

Raymond Chester was at the front rank of American footballers of his generation. He played predominantly at the ‘tight end’ position; if you know, you know; and if you don’t, I could more convincingly explain Euclidean geometry.

The tight end usually receives the ball in an attack on what we call the wing. The well-known Travis Kelce, probably the world’s most famous boyfriend, plays at tight end for the Kansas City Chiefs.

Baltimore

Chester grew up in Baltimore, the fourth of ten siblings. Then as now (remember The Wire?) Baltimore is a seriously tough place for people on the lower economic rungs, which in the 1950s and 60s inevitably meant most black people.

Staying on the straight and narrow was a challenge all by itself.

His parents divorced which, naturally, he found painful. Chester adored his father especially and regarded the attempt to live up to his values of decency and balance as his life’s great work, for which football was in some senses simply a vehicle.

Chester was a gifted all-round sportsman with the physique necessary for football, his standout sport. As a student, he played for Morgan State Bears, a black college team in Baltimore.

Football had begun a slow process of integration from the 1940s onwards but black players in the professional game were still relatively few in the 1960s and the game was a long way from fully integrated.

Chester participated for Morgan State in a 1968 match at the Yankee Stadium in New York against Grambling College Tigers, another black college. It was the first time that two black college teams played at Yankee Stadium, an iconic venue for the sport, and the first to be televised to a mass audience.

A lot was happening in 1968 urban America and the match developed great social significance.

Chester scored Morgan State’s only touchdown and emerged a victorious star. The match generated massive publicity and proved seminal in bringing black footballers from the margins into the mainstream.

Drafted

Chester was drafted into the pro team Oakland Raiders in the NFL in 1970. He had a long career through the 1970s playing for the Raiders (twice) and the Baltimore Colts.

Although Baltimore was Chester’s hometown, he much preferred playing for Oakland, a better and more ambitious team.

His career culminated in 1980 when he became a Super Bowl champion with the Raiders defeating the Philadelphia Eagles.

Shortly afterwards he retired and pursued a career in golf course management.

Chester amassed a long list of sporting honours but has yet to be elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame, a matter of controversy for some.

It’s not possible to talk with any depth about American football without considering the physical impact.

Jon Gower describes impact in plain English using the measure of funfair rides. The impact from a downward rollercoaster ride measures between 3 to 6 g-force. Rugby players can be hit at a force over 10 g multiple times in a match. American footballers can take hits of 25 g, with padding absorbing some of the impact.

Typically, an American footballer spends a lot less time on the field than a rugby player, taking fewer but bigger hits.

Players in both American football and rugby clock-up serious physical attrition in providing entertainment for the rest of us.

Ex-players who suffer a lifetime of aches, pains, limps and operations are one end of the attrition spectrum. Dementia sits at the other.

Both sports are more aware of the dangers today and some better protections for players are in place. On both sides of the Atlantic, however, sad stories compound, legal actions multiply and there is no real answer to the lingering and uncomfortable question about acceptable levels of risk in sport.

Grace

The appeal of Raymond Chester for John Gower is partly based on his sporting prowess and partly on his character. The author is frank in his admiration for the footballer’s grace, his determination to evaluate people on character, not worldly achievement, eschewing braggadocio for modesty and a refusal to be embittered by setbacks.

Chester has a special downer on players “going overboard in celebration after doing something well that is supposed to be a part of the job.” I’m firmly with Raymond Chester and Roy Keane on this.

The relationship between American football and rugby has been stirred recently by Louis Rees-Zammit’s attempt to follow the International Player Pathway to break into the sport. It’s not clear yet whether he’ll succeed ultimately, but you can hardly blame a man for following his dream.

On the sports field itself, measurable talent is the yardstick. The majority of NFL players today are black while most coaches are white.

Given that most coaches are former players, you wonder why this is and observe that equality feels incomplete.

A similar situation applies to the Premier League and rugby; the greater number of black players doesn’t result in many black managers or decision-makers.

Raymond Chester was part of a major step forward in sport and society in America but there’s further to go and other dreams to be realised.

Raider: The Raymond Chester Story by Jon Gower is published by Calon and is available from all good bookshops.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.