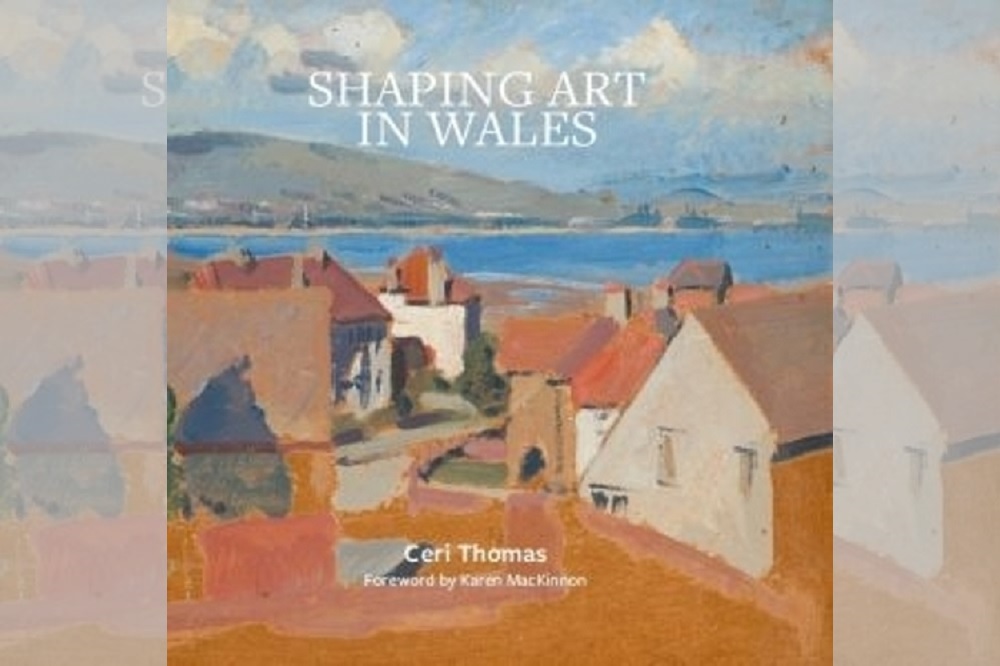

Book review: Shaping Art in Wales – David Bell, Kathleen Armistead and the modern artist By Ceri Thomas

Sarah Tanburn

‘A city’s art collection is a living, breathing thing, constantly changing and in conversation with what went before and what comes after. Each work and period of time is in dialogue with the broader culture and society in which it finds itself.’

So says Karen Mackinnon, current Curator of the Glynn Vivian art gallery in Swansea. She is writing in her introduction to this comprehensive study of the work of her predecessor in the 1950s, David Bell, and his immediate successor, Kathleen Armistead.

Mackinnon’s comment is an important contextual reminder: at any given moment the works purchased, exhibited or commissioned in public spaces, especially those procured through public funding, are subject to intense scrutiny and critique.

Any commentary, however knowledgeable, passionate or creative the speaker, is also subject to its time and place.

Even so, Ceri Thomas, in this detailed study, particularly in writing of David Bell, has offered important clues as to the wider, longer-lasting work of a curator, collector or commissioner on a mission.

Bell was Assistant Director at the newly formed Welsh Arts Council from 1946 to 1951, and then Curator of the Glynn Vivian till his early death in 1959.

Throughout this time he was driven to build the presence of painting as a part of the Welsh cultural landscape, both by bringing major exhibitions and works to Wales and by encouraging a stronger presence and capacity of painters in the country.

By commissioning and buying work, active arts education and a robust media presence he really grew the knowledge, appreciation and output of painting throughout those years.

He was followed at the gallery by Kathleen Armistead, who also worked at education, public discussion and building opportunities for awards and competitions.

She was more interested in sculpture and ceramics and acquired several important pieces for Swansea. It is clear, though, that Thomas’s real interest is in Bell and much of this book is devoted to him.

In addition to much information and material, this is a beautiful book, filled with reproductions of works mentioned in the text.

The H’mm Foundation are to be commended on the quality of production and their faith in its importance.

An ongoing story

I would not claim to be a knowledgeable art critic and I will not comment on the many fallings-out and doctrinal differences Thomas alludes to in these pages.

The turn away from representation to more abstract work in the 1960s came from many complicated inspirations.

For the non-cognoscenti, I recommend Huw Stephen’s’ 2023 series, The Story of Welsh Art from the BBC which, amongst other things emphasises the breadth and wealth of visual works in this country.

In this review, I don’t need to add to the many voices pointing to the lack of opportunity for female artists or artists of colour in our cultural institutions, though I agree with them.

I must remark, though, that both Bell and Armistead obviously wrote often for local papers, as Thomas cites many articles containing knowledgeable discussions of work on show.

Such well-read and accessible information about art – far beyond the two-line listing – is missing today.

I could perhaps get stuck into the endless discussion of what ‘art in Wales’ or ‘Welsh art’ might be. Are we talking about someone born and living here, or born here but living elsewhere?

Or, like several artists cited here, born in other parts of the world but making their home here. It is noticeable, amongst present day uproars, that refugees from European fascism made major contributions to the story of art in Wales.

And must Welsh art in some sense be inspired by the Welsh environment and landscapes or can it move away from that subject matter completely?

Thomas makes some interesting observations and inclusions on this front, on which many readers might have an opinion.

Those views will be better informed after reading this book.

Who pays?

Thomas’s study brought up a rather different reflection. Threaded throughout those post-war decades is the debate on patronage.

Who pays for new work, or for the exhibition and management of work within our galleries and other spaces. And what do we expect such patronage to achieve?

It is not strictly accurate to say that almost all patronage (of 2D visual arts in Wales) was in private hands prior to the 1939-1945 war.

For centuries, the church was a central commissioner, and the wall paintings in churches from Holyhead to Llancarfan, including post-Reformation monochrome inscriptions, are their own tradition.

It is, though, broadly true that Wales lacked the kind of patronage that saw so much visual art explode in England in the 17th to 19th centuries, or the print broadsheets that developed satirical visual literacy in many industrialised working-class areas.

The role of the Arts Council and public galleries or museums was therefore crucial in enabling access to contemporary work and building understanding of the medium, and Bell was at the heart of the business for those 13 years.

Much of what was bought or commissioned followed his aesthetics and priorities. Armistead, too, had enough of a budget in her own hands, through the gallery’s Friends, the local authority and other sources to have a significant acquisitions programme.

One might not agree with them about their priorities or choices, but it is interesting to achieve a better understanding of why they bought the objects they did, and how those pieces contribute to the development of arts understanding here.

Thomas himself generally seems to refrain from expressing his own views on the art-works; his enjoyment of Ceri Richards La Cathédral Engloutie III alongside his quotation of Armistead’s praise for Bell’s own pencil portrait Miss Phillipa Fawcett show his own wide-ranging taste, while his erudition is undeniable.

In considering who acquired what and why, Thomas is a safe pair of hands.

Aneurin Bevan, writing in 1952, said, ‘[i]t is tiresome to hear the diatribes of some modern art critics who bemoan the passing of the rich patron as though this must mean the decline of art, whereas it could mean its emancipation if the artists were restored to their proper relationship with civic life.’

Bell and Bevan were working before the explosion of energy and democratisation of the 1970s and beyond but it was the work of curators and leaders such as Bell and Armistead who laid the foundation for that growth in understanding and access.

It feels unreal, today, to imagine or remember times when the public purse was both able and willing to invest in the cultural well-being of the people. Instead, museums are closing, few publicly-run art galleries survive, and those that do are expected to meet stringent income targets.

The benefits

Yet, I write this at a time when the Post Office scandal is at the forefront of public debate, thrust there after decades of struggle by a series in the visual medium of television.

Amongst the many lessons of that appalling miscarriage of justice is the importance of creativity in showing us the world we live in and enabling us to understand and change it.

The impact of Mr Bates vs The Post Office is not a failure of journalism but a triumph of art.

As a society, not only as governments, we need to rethink and revitalise the importance of all forms of art – including painting and sculpture – in our civic and political life.

Emergency Foil Blankets by Daniel Trivady, which won the Gold Medal for Fine Art at the National Eisteddfod in Llanrwst 2019, is an excellent example of the blurred boundaries in art forms and the value of such work in the debates about what sort of Wales we want to become.

Beyond the scholarly detail, this is perhaps a key value of the book – that it forces us to re-examine the importance and role of art in the public sphere. Here, I mean painting and sculpture rather than those performance arts (music, poetry, drama) at which Wales has excelled.

Whether we look at Guernica, or the controversial post-referendum exhibition by Iwan Bala in Penarth, the biological yet abstract work of Sue Hunt or the painstaking anatomical detail of Cath Janes, the debates motivated by paintings and two-dimensional art, the reflections and inspirations enabled, are central to a full and human engagement with the world around us.

Shaping Art in Wales : David Bell, Kathleen Armistead and the modern artist by Ceri Thomas is published by H’mm Foundation and available in all good bookshops.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.