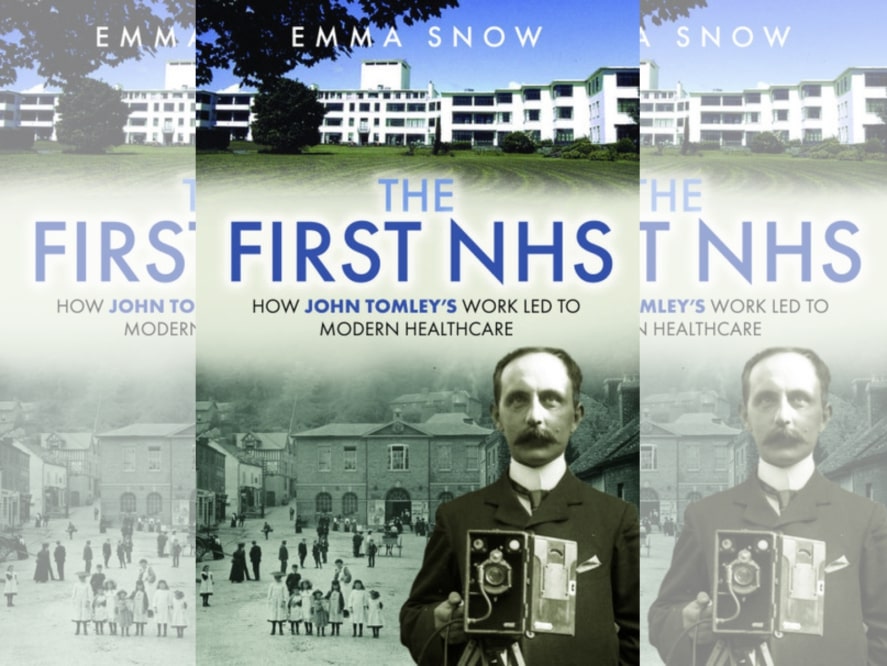

Book review: The First NHS by Emma Snow

Jon Gower

Think of the founding of the National Health Service and there’ll probably be only one name that springs to mind, that of Aneurin Bevan. But the creation of that pillar of British society was set on foundations already created, as this book shows. It included work done by a surprisingly broad range of concerned players including ‘the Oddfellows, the Liberal Party, Winston Churchill, the Daily Mirror and even the Druids.’

The First NHS tells the story of one overlooked player in that story, namely John Tomley, born and brought up in Montgomery, where his father Robert worked in a local workhouse. As a boy John enjoyed playing football and cricket on community pitches. In a key moment in his life, at the age of 11, he met Wales’ first millionaire, David Davies MP, who was also one of the country’s first philanthropists. This was a seed in an important later friendship.

After secondary school John went to work for a local solicitor and kept up his cricketing skills: one year his team stared defeat in the face ‘but the plucky play of a young batsman, Mr J.E. Tomley, turned the tables and secured for them a brilliant victory,’ as a speech at the cricket club dinner put it.

In 1891 John went to his first meeting of the Montgomery Loyal Ark of Friendship Lodge of Oddfellows, a rather high-faluting name he himself explained as having its origins in the 1840s, when there was ‘much agitation as to the condition of employment and of the working classes, and the Chartists were in existence. At the same time, there was an undercurrent of thrift and self-reliance, and it was that which led to the formation odf the friendly societies… “Ark” meant refuge, and the lodge was a refuge for those who were in times of difficulty.’

By the age of 19 John was the youngest branch secretary of the Oddfellows in the country. Meanwhile, his progress in the law saw him qualify as a solicitor and a local law firm was renamed ‘Pryce, Tomley and Pryce.’

Having seen conditions for poor people at the local workhouse he began to fight poverty, or as he called it pauperism, being the legal term of the day, writing cogent letters to the press at the same time as the Labour Party was being founded. In his articles, taken up by the Manchester Guardian, he showed how friendly societies helped lessen the burden of poor relief.

Sanitation

The late 1800s and early 1900s were a time when illnesses such as TB, cholera and typhoid were rife across the whole of the UK, exacerbated by a lack of decent sanitation.

Along with David Davies MP, who was by now Tomley’s friend, steps were taken to pilot the first ever national health service. This was a body called the King Edward VII Welsh National Memorial Association with its ultimate object being to stamp out TB. The disease caused at least 40,000 deaths in England and Wales each year and cost the government £8 million. The WNMA was set up at about the same time as David Lloyd George and the Liberals’ National Health Insurance Bill, with the state, too, thus stepping in to bat. In train, Tomley delivered lectures across Wales, advocating on behalf of the new National Health Assurance Commission, the precursor to the Ministry of Health, the first instance of Tomley working directly for national government.

Crusade

The WNMA had got off to a good start, with its first medical director appointed in 1912 to lead the ‘Welsh Consumption Crusade.’ Meanwhile, John kept up his work with the Oddfellows, chairing its Investigations Committee and becoming one of the experts who gave evidence to the British government when they were looking at old -age pensions. He argued that two thirds of the people over 70 in Montgomery were eligible for the pension while the other third were not. He therefore argued that the rate needed to be set high enough to buy essentials, especially as their prices has risen as a consequence of the war. The war has also led to the widespread presence of TB in consumptive soldiers. Children, too, suffered by the hundreds, leading to the opening of the first children’s hospital for TB in St Bride’s in Pembrokeshire, followed by a state-of-the art provision in Sully on the south Wales coast.

By 1921 the Friendly Societies were suggesting a national health service should be established but by the following year health care was facing the Geddes Axe, a cost-cutting exercise driven by Sir Eric Geddes, who had served as director-general of munitions and railways in the war.

John Tomley wasn’t just a campaigner against poverty and for better health provision in his role as local health commissioner. He argued for more telephones in rural Wales for instance. He also diligently kept up his connections with the friendly societies’ movement, with its twelve million members, becoming its president in 1937. This was a time when TB figures were beginning to fall, although little seemed to be happening directly as a consequence of the TB inquiry which reported that ‘There are houses with roses round the door, but inside they are not fit for people to die in, never mind live in.’ Medical officers despaired as houses were condemned, and their occupants moved out, only to see others move into the same squalid hovels. Malnutrition, or semi-starvation also played its part in a country with ‘no fires even though coal is running to waste.’

Evil of want

The Second World War slowed down much of the momentum in discussing and solving social problems, although the Beveridge report, ‘a scheme to deal with the evil of want’ was published in 1942, eventually becoming the basis for ‘so many of the idealistic reforms of the postwar government.’ Enter Nye Bevan and a story much more familiar than that of John Tomley’s. John died at home in Montgomery in 1951, aged 77 years of age and he and his wife Edith were cared for free of charge by the NHS at the end of their lives. There had been great progress.

All of this hard-working and dedicated life is presented in the pages of The First NHS by Tomley’s great-great-granddaughter, Emma Snow who not only works for the NHS but has herself been the beneficiary of medical research. Her family has suffered through the generations from the genetic Huntingdon’s disease and so know the system, and the need for medical care most intimately well.

The author closes her biography of Tomley with an analysis of the NHS today. It makes for cogent, trenchant reading, arguing that the ‘advances which were made when the welfare state was started, and since, have been eroded over time. When people ask the government to spend more on one thing, another thing has to be cut to pay for it, and sometimes it is the wrong things.’ In examining such matters as A&E waiting time and the use of hard data Snow formulates her own key policy asks for today, such as exploring multigenerational health inequalities; allowing those who are going to die early to have their savings disregarded when it comes to care costs; creating a new Beveridge report and the provision of ‘full death statistics on underlying cause of death, so bringing together groups of similar conditions for research and treatment.’ In arguing for these improvements and more she seems to be acting very much in the spirit of John Tomley himself, similarly analysing and advocating as part of the still ongoing drive for a fairer, healthier society.

The First NHS: How John Tomley’s Work Led to Modern Healthcare by Emma Snow is published by Pen and Sword History. It is available from all good bookshops.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.