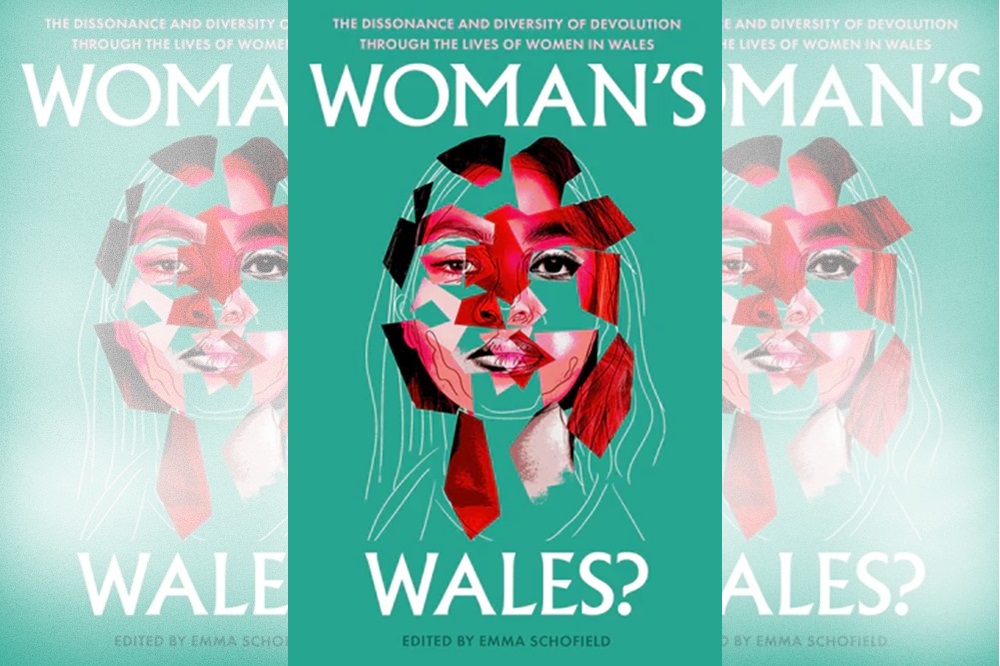

Book review: Woman’s Wales

Can we see equality from here?

Sarah Tanburn

Woman’s Wales is the latest exploration of the workings of devolved government here, edited by Cardiff University’s Emma Schofield. She has brought together 13 interesting writers for this volume reflecting on a quarter of a century of avowedly feminist government, who give what is now the Senedd decidedly mixed reviews.

In her introduction, Schofield ponders on the necessity to keep arguing for equality. These essays suggest that argument is well won. It’s how life works for women in Wales on which progress must be judged.

Each contribution brings its own insights into the author’s key concerns, ranging from broadcasting to health, from presence on public bodies to climate change and the state of cultural funding. Some contributors reflect on other aspects of exclusion, such as race or disability, bringing those intersections into focus. Across the collection, several themes emerge.

Motif

The strongest motif is the gap between planning and execution. The government of Wales, from the start of devolution, has had high ambitions for the female 51% of the population. Action Plans for this and Strategies for that have proliferated but time and again outcomes are inadequate. Nanci Escott and Jessica Laimann, of the Women’s Equality Network, point out that ‘childcare sufficiency in Wales is the lowest [in Britain] … in 2023 [provision] was 94% in Scotland, 66% in England and only 37% in Wales.’ Childcare is fundamental to women’s participation in the workforce, economic independence and opportunities, so such a statistic is a shocking indictment of Senedd priorities, not to be explained by workforce shortfalls alone.

Stories of dysfunctional, unfocused care during childbirth are horrific, especially the racism reported by Escott and Laimann or the paucity of support during Covid experienced by Marie Ellis Dunning. Dunning also emphasises the ways in which women’s pain associated with contraception, menstruation and menopause are routinely belittled or ignored. Systemic failures of provision have been highlighted again recently by the BBC report on the country-wide shortfall in abortion services.

The lack of a specific Women’s Health Plan is perhaps relevant, but the more fundamental issue is a culture in which women’s experience, needs and expectations are routinely dismissed, including by women themselves. Rae Howells emphasises, in the context of environmental collapse, Welsh Government must ‘be even bolder … and crucially deliver,’ (her emphasis.) It is not good enough to have a plan if quotidian decisions and institutional culture are barely touched.

The roundtable discussion with some of our most respected female journalists reported by Cerith Mathias demonstrates that, despite a strong start, the power and presence of women in front of and behind the cameras, has waned. In the early noughties, the ambition to do things differently from Westminster drove a high proportion of women in political editorial and broadcast, so often a boy’s game. Yet, as Jo Keirnan says, ‘in a way I think we’ve gone backwards … the optimism we all gad at the turn of the century has not lived up to our expectations.’

Decline

She and her colleagues point to the significant decline in Wales-specific political coverage and leave open the question of women’s involvement in news content for social media. There is considerable additional work needed here to understand what is happening, particularly in the fast-changing world of online reporting, citizen journalism and the challenges of fact-based, properly evidenced reporting. The changes, and lack of investigation, are of a piece with the change from the relative support and financial underpinning of the Blair years to the hostile austerity experienced since 2010.

The loss of women to political journalism is perhaps a better example of regression than the much-discussed issue of women’s representation in the Senedd. Nearly every contributor laments the fact that since the world-first gender parity of the Senedd in 2005, our parliament now lags Scotland with 43% female membership. This is still far better than at Westminster (35%), and in such a small legislature it only takes one or two to make a difference.

Perhaps more concerning is that less than a third of party candidates were women in 2021, changing which failure is the objective of the current Electoral Candidate Lists Bill, as the writers from WEN suggest. I see several challenges in the approach they favour, but one lies clearly in electoral history. Welsh Labour has dominated Welsh governance for over a century and throughout devolution.

They have consistently worked to ensure the selection of women, including through all-women shortlists, and currently hold nine of 14 Cabinet posts. Women have held key roles in finance, health, social care and equalities, and the permanent secretary in charge of the Welsh Civil Service has been a woman for nearly a third of the time.

Women have held real power in WAG and today in the Senedd (although much less so at local government level) yet it is clear from the failures of delivery that this has not been enough to address endemic failures of service and accountability. Jasmine Donahaye, discussing the erasure of women, especially women of colour, from the cultural life of the nation, says that ‘the statues of Betty Campbell, Elaine Morgan and Cranogwen … stand as monuments to continued inequality.’ A higher profile and wider representation do not inevitably lead to change.

Positive steps

Some elements of analysis by these writers might be challenged besides recognising the power women have held. Dunning argues powerfully for sex education, but fails to recognise that some of the opposition to the current curriculum is rooted in its content, not its mandatory nature. Safe Schools Alliance (amongst others) has produced a critique of that content, while Merched Cymru shares many of Dunning’s perspectives. but encourages parents to be properly informed about such teaching. (Neither group has any affiliation with the campaign she references.) It should be a matter for congratulation that there is diversity and plurality of women’s voices in political debate in Wales.

Of course, we have seen significant improvements in some areas. Norena Shopland sets out some of the milestones from the infamous section 28, which banned the ‘promotion of homosexuality’, still in force when the Wales Assembly Government came into being, and today’s widely publicised LGBTQ+ Action Plan. Dr Michelle Deininger praises the funding available to mature and part-time students, particularly valuable to women, where the devolved government has made a real difference.

Woman’s Wales should be read by anyone concerned with women’s roles in Welsh life an politics. Schofield reminds us of the centrality of daughters to our ambitions – those physical, intellectual and political descendants for whom so many of us do the work.

She rightly urges us ‘to keep on asking questions about how we can make things better, however difficult those questions may be to answer.’ Her collection gives devolution a passing mark, with a ‘could do better’. This is no time to give up on the debate but rather to keep pushing to make our country one in which women are genuinely leading, are heard by those with power and well served in all parts of our lives.

Woman’s Wales: The Dissonance and Diversity of Devolution through the lives of Women in Wales is edited by Emma Schofield and published by Parthian. It is available from all good bookshops.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

I applaud this book, but I really don’t understand any woman lauding the LGBTQ+ Action Plan. It purports that being a woman is nothing more than a state of mind; that any man can become a woman just by declaring himself so. The WAG is, of course, fully signed up to all such claptrap.