David Jones and Capel-y-ffin: Arrival

In the first of a series of articles about the painter-poet David Jones and his relationship with Capel-y-ffin, Peter Wakelin recounts Jones’s arrival in 1924.

Intense experiences of new places can be turning points in the creative lives of artists. David Jones identified his periods living and working at Capel-y-ffin in the mid-1920s as ‘a new beginning’. So sure was he of his new direction that soon after started work in the Black Mountains he went home and burned almost all his earlier paintings.

Jones was 29 when he arrived at Capel. After years of art training and then service in the First World War (the ‘parenthesis’ as he called it), he had not yet found his direction as an artist. Yet within a decade Kenneth Clark, then Director of the National Gallery, could describe him as ‘the most gifted of all the younger English painters’. He was called a genius byT. S. Eliot and Igor Stravinsky, among others, after his epic poem In Parenthesis was published in 1937.

His first visit to Capel-y-ffin began just before Christmas 1924 and lasted ten weeks. He came and went for many others visits, spending a total of some 48 weeks there until early 1927.

That first day, 22 December 1924, was a kind of homecoming. Jones had grown up at Brockley in south London with an intense awareness of his Welsh heritage. His father came from a Welsh-speaking family at Holywell in north Wales and David’s first arrival on Welsh territory as a small child was a potent memory: ‘I remember feeling some rubicon had been passed and that I was now in the land of which I had heard my father so often speak.’ At home, he read about Welsh history, heard his father sing Welsh songs and explored the literature of the country.

At Capel, suddenly, he was in the middle of this heritage: encountering the landscape, decoding place names and imagining hillside ponies as the descendants of those that carried the Gododdin or Arthur’s knights to battle. He was in a border country of the deep past, ‘a land of enchantment’.

He was collected at Llanvihangel Crucorney railway station by the artist and designer Eric Gill for the 9-mile onward journey by pony and trap. They followed the narrow valley of the Honddu, winding between mountain ridges, their lower slopes clothed with woods, their heights dramatized by crags.

They passed Llanthony Priory, the ruin that enticed touring artists in the Romantic era, and at the hamlet of Capel-y-ffin, they turned left towards the valley of the Nant Bwch, which is divided from the Honddu by the ridge of Darren Lwyd, appearing from downstream as though it might be a conical mountain on its own. They were near their destination, the Victorian monastery on the north-facing slope above the confluence of the streams.

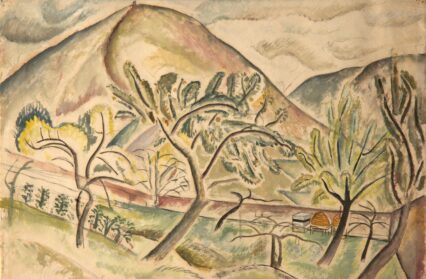

The Nant Bwch valley and the view towards Darren Lwyd, which appeared from downstream as though it might be a conical mountain on its own, would be keys to Jones’s vision. He called the valley sometimes ‘Honddu Fach’ (‘little’ Honddu) and the mountain ‘Twmpa’ – though on maps that is name for the summit of the ridge, 2 miles away.

Jones had met Gill in 1921 and had become a frequent visitor to the Roman Catholic guild he had set up with others at Ditchling in Sussex. In April 1924 Jones became engaged to Gill’s daughter, Petra. Gill leased the monastery at Capel-y-ffin from that August, after deciding to split from the Ditchling community and head for the hills. Its isolation delighted Gill – the postman rode on horseback and the only doctor came once a week 9 miles from Hay-on-Wye. It must have felt a very long way from the Roaring Twenties.

Eric Gill aspired to a Roman Catholic community that made art and was partly self-sufficient. It comprised Eric, his wife Mary and their children, Betty, Petra, Joanna and Gordian, joined from the start by three more families – the Hagreens, Brennans and Attwaters – and Denis Tegetmeier. A few monks still occupied the farmhouse, with a young associate called René Hague.

The monastery was 350m above sea-level and the mountain moorlands rose 250m on either side. In that first winter, it still had broken windows and holes in the roof. The unfinished church was falling down so Mass was held in a temporary chapel in the south range. Jones was given one of the screened-off monks’ cells under the roof. It was bitterly cold.

The landscape of enclosing mountains and rushing streams was quite unlike the places David Jones had known before – London, the rolling hills of Sussex and the flatlands of the Somme. For a visitor today, its secret existence among enfolding hills is still a source of inspiration and still evokes a sense of spirituality. For David Jones in 1924 it was an instant invitation to start painting, and almost immediately to discover a new direction in his work.

The exhibition Hill-rhythms: David Jones + Capel-y-ffin continues at y Gaer: Brecknock Museum, Art Gallery and Library every day until 29 October 2023, admission free.

This article draws on Peter Wakelin’s book to accompany the exhibition, published by the Brecknock Art Trust and Grey Mare Press.

David Jones’s ‘Twmpa’ from Capel-y-ffin. Photo: Peter Wakelin

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.