David Jones: In Print

In the fourth and last of a series of articles about the painter-poet David Jones and his relationship with Capel-y-ffin, Peter Wakelin described the high point in his career as an illustrator and engraver.

At the end of the First World War, David Jones returned to art school with an ex-serviceman’s grant, then began attending Eric Gill’s community at Ditchling as an informal assistant. After struggling with carving, he turned to wood-engraving.

By the eve of his arrival at Capel-y-ffin late in 1924 Jones had completed his first full illustration commission, The Town Child’s Alphabet, a children’s book of humorous character studies. During the next few years his development as an engraver would establish him one Britain’s finest illustrators. And yet by 1930 his career as an illustrator was all-but over.

Focus

In the years when David Jones was visiting Capel-y-ffin regularly between 1924 and 1927, engraving was his greatest focus other than landscape painting.

The monastery was well-provided for printmaking: Gill had three presses there for his own work, which Jones was able to use to experiment and proof his blocks. He carried his tools with him as he travelled between Capel, Caldey Island and his parents’ home in Brockley.

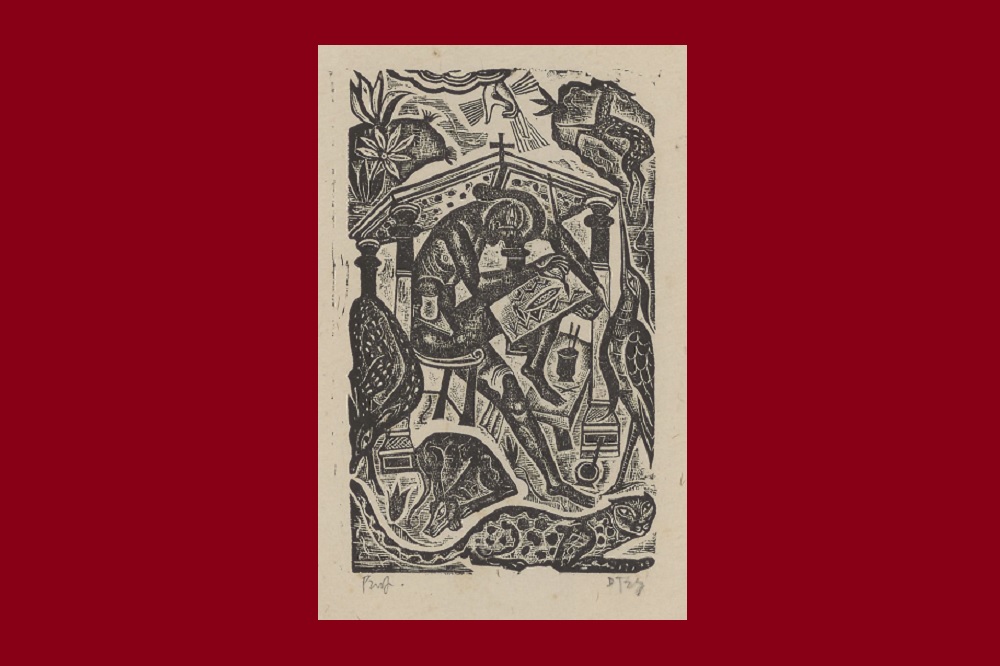

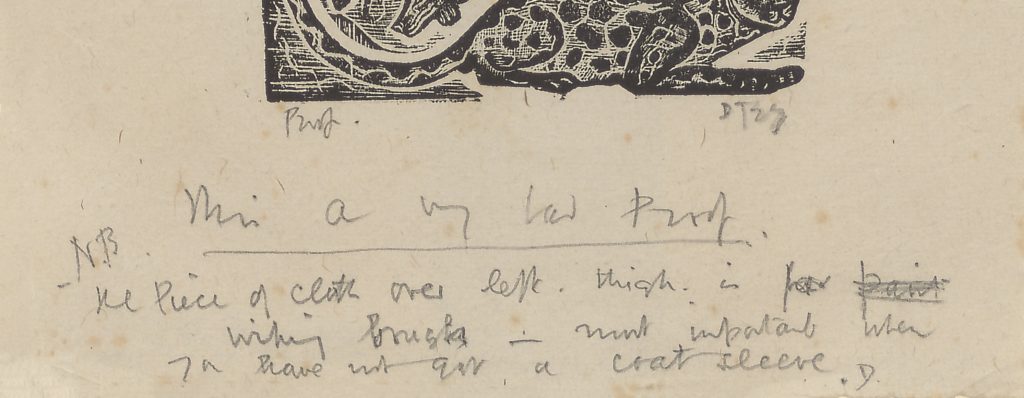

His wood-engraving frontispiece to Gill’s book Christianity and Art, published at Capel-y-ffin, can be read as a self-portrait. Jones envisaged himself in the tradition of medieval illuminators in religious communities.

The artist is encircled by Creation as his subject matter and working under the hand of God. In a note on the proof at the National Library of Wales Jones joked: ‘The piece of cloth over left thigh is for wiping brush – most important when you have not got a coat sleeve.’

The technique of wood-engraving involved incising fine cuts in woodblocks then inking the surface to print dark grounds on which the cuts showed white. While many artists cut back to make large areas of white, Jones gradually developed a preference for making full use of the surface of the wood so that his prints read more often as white lines on black.

Expressionistic

While staying at Capel-y-ffin in March 1925, Jones met Robert Gibbings, the owner of the Golden Cockerel Press, who immediately commissioned him to illustrate Gulliver’s Travels. It was a large project for which he made 42 expressionistic wood-engravings. The book was published in 1926.

During the snows of early 1925 he had begun using Gill’s etching press to try copper-engraving. His first image was of the mountain above Capel.

The engraved copper plate was inked and wiped clean, then pressed hard into paper to transfer ink held in the engraved lines. He had to teach himself how to make best use of this new technique, but in time he could draw with a burin on copper as fluidly as he drew his watercolours.

Faith

In 1926 and early 1927, he brought into his designs in wood-engraving the fluidity of line he had learned from landscape painting and copper-engraving. He produced two wood-engravings for the Gregynog Press edition of the Book of Ecclesiastes, Llyfr y Pregeth-wr.

He also began another illustration project for the Golden Cockerel Press. This would be his masterpiece in wood-engraving, the story of Noah’s Ark from a cycle of medieval miracle plays: The Chester Play of the Deluge. It was a project that expressed his deeply held faith as well as his art.

The ten images are rhythmic and balanced even though they are so densely detailed with interlocking shapes. In one of the finished illustrations, Capel’s pigs are running with bears, giraffes and other beasts.

In another, local herons are in flight. Capel’s hills provide the setting, most unexpectedly in ‘The Dove of Peace’. In this, the ark rides above the mountains of Ararat, where it will settle. The submerged mountain is Jones’s ‘Twmpa’ of so many Capel paintings, the distinctive bulge clear on its left flank.

Flowing style

His last great illustration project, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner was initiated by the Bristol bookseller Douglas Cleverdon, who visited Capel-y-ffin in 1926 when he was 24. Cleverdon saw Jones’s first copper engravings and borrowed money from his father to commission Jones in his new, flowing style.

Jones started it after finishing the Deluge in 1927 but he was having many problems. He wrote: ‘My eyes have gone worse … it would be so utterly ghastly to have to give up engraving altogether … I have such tons to do.’

Nevertheless, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner was published in January 1929 and is recognised as one of the great modern illustrated books.

It was a bitter irony that, having become one of the country’s most highly regarded book-illustrators, Jones made only around a dozen further prints. He hoped to work with Cleverdon on an edition of Morte d’Arthur, the great work he had read with the community at Capel and that would feed his literary and artistic imagination in future.

However, he struggled with his health and wrote in 1929: ‘The thing is just beyond me at the present time … I have done no work for ages – it’s detestable to never feel fit for anything …’. The book was never completed.

Important

In 1928, he began writing the text that would establish him as one of the most important modernist poets of the century. He started making images while in bed with flu about his experiences in the Royal Welch Fusiliers.

At first he wrote ‘as a sort of running commentary’, but the writing became more important to him and evolved into his epic poem In Parenthesis. After completing a full draft in 1932, he had a breakdown.

The book combines an autobiographical narrative with layers of allusion to Welsh literature and history, mythology and Henry V. On publication in 1937 it was hailed as a masterpiece.

He had barely been able to paint or draw for the past five years and he was not well enough to illustrate In Parenthesis as he had intended. His drawing for the frontispiece was reproduced photographically rather than remade as a wood-engraving.

Although Jones never engraved again after around 1930 he had his ink, copper plates and other printing paraphernalia with him when he died. Tom Dilworth has suggested his eyes may have been affected by something as simple as an undiagnosed vitamin A deficiency.

The exhibition Hill-rhythms: David Jones + Capel-y-ffin continues at y Gaer: Brecknock Museum, Art Gallery and Library every day until 29 October 2023, admission free. The introductory film for the exhibition can be viewed here.

This article draws on Peter Wakelin’s book to accompany the exhibition, published by the Brecknock Art Trust and Grey Mare Press.

Read the other installments in this series here

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.