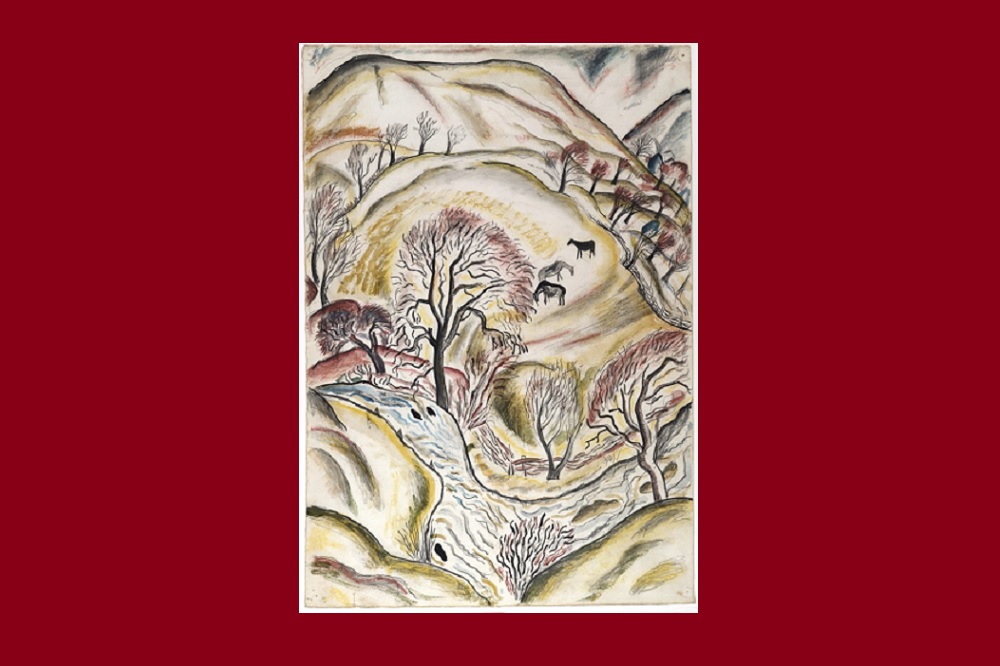

David Jones: Tir-y-Blaenau

In the second of a series of articles about the painter-poet David Jones and his relationship with Capel-y-ffin to accompany the current exhibition at y Gaer in Brecon, Peter Wakelin writes about the immediate impact the Black Mountains had on Jones’s painting when he arrived in 1924.

From the moment he arrived at Capel-y-ffin, at Christmas 1924, David Jones was set challenges by the landscape. Its enclosing mountains were quite unlike the places where he had worked previously, and he felt the different history of the borderlands. He could not frame a traditional landscape composition of foreground, middle-ground and distance.

Even the Welsh father of British landscape painting, Richard Wilson, had stepped back from mountains to depict them. Here, the subject was close and rose up to fill the view. When Eric Ravilious came in Jones’s footsteps to paint at Capel a decade later he joked: ‘the hills are so massive it is difficult to leave room for them on the paper.’

Jones started painting outdoors, working quickly in the cold. In almost certainly his first picture, Tir-y-Blaenau, he hit immediately on the way forward, though he seems to have chosen the mountain on the east side of Capel rather than the one that he called Twmpa and would prove to be his favourite, at the southern end of the Darren Lwyd ridge. (He appears to have been looking up to a bulge in the Hatterrall Ridge, just south of the Capel, rising above the fields of Blaenau farm.)

The breakthrough of Tir-y-Blaenau freed him from the polite organisation of his previous landscapes. Jones would never part with the painting, hanging it over his bed. He said it was the one from which all his ‘subsequent watercolour thing … developed.’

Tir-y-Blaenau displays precisely the ‘strong hill-rhythms and the bright counter-rhythms’ of the river that Jones talked about later, the convex arcs of the mountain and the field below it mirroring the concaves of the two riverbanks. The right side seems to be spinning away, the trees growing at right-angles to the slopes, but the composition is stilled by the standing horses and bound together by newly laid hedges and spreading branches.

He gives more-or-less equal tones to the far summit and the foreground river, compressing distance. The intersecting arcs imply an underlying circle. Jones wrote later: ‘it is an abstract quality, however hidden or devious, which determines the real worth of any work.’ The hill, field and river also suggest an anthropomorphic sensibility, relating the landscape to the human figure, which he would pursue decades later in his poem ‘The Sleeping Lord’.

‘Live’ painting

Tir-y-Blaenau was a breakthrough in technique too. He said he needed to be outdoors to capture the tensions that made for a ‘live’ painting, whereas working from memory produced easy lines and boring rhythms. He went out with a board to which he pinned his paper. Working in all weathers made him work fast.

He used crayon and ink fluidly and sparingly and watercolour translucently so that the white of the paper lends the whole a mid-tone that was to characterise almost all his work from this date onwards. He enjoyed watercolour’s transparency, which permitted images to overlay one another – an equivalent of experiencing the world, where attention shifts and vision persists. As David Blamires wrote in 1989 (Austin/Desmond Fine Art, David Jones 1895-1974):

He quickly developed an idiosyncratic use of pale colours, applying them discontinuously in dabs and strokes, so that the effect is almost disconcertingly vibrant. One never feels that a scene has been captured in the timeless still, but rather that it is still moving, that the water is rushing on, the trees are swaying in the breeze and the light is just changing.

The paleness and tentativeness was a great change from his recent work. It was perhaps expressing a feeling that even as he saw more, he knew less. It was the beginning of a two-year period when his work would be transformed, he would start exhibiting among the leading modernists and he would be recognised as one of the most gifted British artists of his generation.

The exhibition Hill-rhythms: David Jones + Capel-y-ffin continues at y Gaer: Brecknock Museum, Art Gallery and Library every day until 29 October 2023, admission free.

This article draws on Peter Wakelin’s book to accompany the exhibition, published by the Brecknock Art Trust and Grey Mare Press

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.