David Jones: Wood and Water

In the third of a series of articles about the painter-poet David Jones and his relationship with Capel-y-ffin, Peter Wakelin writes about the development of his approach to landscape.

In an autobiographical talk broadcast in 1954, David Jones said:

It was in the Black Mountains that I made some drawings which it so happens, appear, in retrospect, to have marked a new beginning … It was at this propitious time that circumstances occasioned my living in Nant Honddu, there to feel the impact of the strong hill-rhythms and the bright counter-rhythms of the afonydd dyfroedd which make so much of Wales such a ‘plurabelle’.

Although he had identified all the elements of his new style in his first painting of Capel-y-ffin at Christmas 1924, Tir-y-Blaenau (article 2), he continued to test out different approaches.

When his first New Year at Capel snowfall kept him indoors until the drifts were melting he said he ‘liked the look’ of them though they gave him ‘a kind of ill-at-ease feeling almost of foreboding.’ In response he tried out a naïve style, perhaps influenced by seeing paintings by André Derain or Ben Nicholson.

He responded to objects that interested him with directness and simplicity rather than naturalism, often clarifying their shapes with line or bringing them forward with a pale rim. In one painting the disappearing snow reveals remains of tree-felling, which might have recalled for him the aftermath of wartime shelling. He makes strong features of trees and logs, roads swooping into the distance and the wall that separates the woods and fields from the mountainsides above.

The next year, 1926, was the annus mirabilis of Jones’s painting at Capel. He was there for half the year in total, in winter, spring and summer, out in nature drawing obsessively even though he was working on major illustration commissions. He alternated between paintings that brought together all the characteristics of his new landscape style and others in which he tried varying approaches.

In June he painted a view of a cascade on the Nant Bwch on toned paper in dense gouache. The warm colour and luxuriant vegetation seem fantastical, evoking The Lost World or the Garden of Eden. Yet from around the same time another painting of the stream employed translucent washes that leave white paper and fine work in pencil.

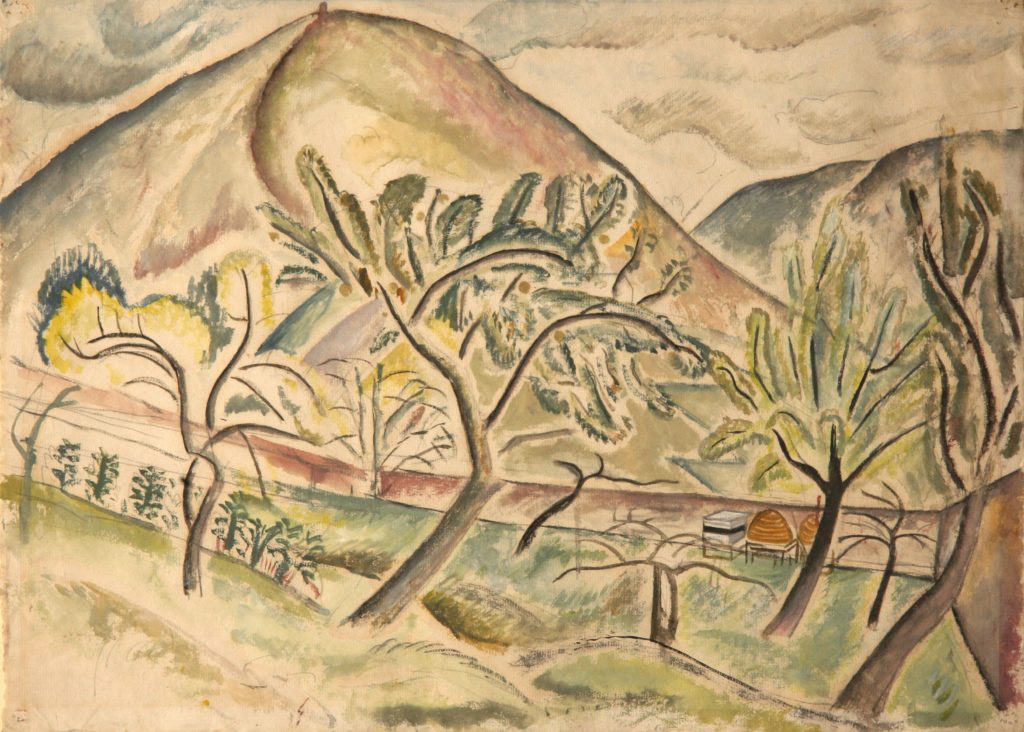

In several paintings of the orchard at the monastery he tried a Fauvist idiom that employed opposite colours to create an energetic effect, perhaps influenced by Henri Matisse or André Derain. In one that looks diagonally down the orchard, northwards to the sheltering mountain he celebrates the Capel community’s husbandry of the land: fruit on the apple trees, vegetable plots, straw bee-skeps and a wooden hive, new saplings planted alongside the bent old apple trees.

Jones got to know his subjects intimately – the mountain with its skirt of woodland, the hillside farm, the monastery barns and the little stand of trees in the field below. Pale tones, delicate marks and prominent pencil under watercolour would be distinctive qualities of his paintings for the rest of his life, as was his ability to pick out emblematic details without unbalancing the composition.

It is clear that he was seeking significance in his paintings by this time; not just records of topography but signs of something beyond. His woods suggest sometimes the mystery of a refuge or a sacred grove, and a few years later In Parenthesis would conjure a Queen of the Woods to bestow foliate tokens on the fallen.

The geographical reach of Jones’s painting at Capel was constrained. All his subject seem to lie in the valley of the Nant Bwch, many of them within a hundred paces of the monastery. He seldom drew on the open hillsides – perhaps preferring the trench-like protection of the valley, the more so as his agoraphobia worsened.

He took no interest in a wealth of other prospective subjects. He did not walk down to Llanthony Priory in homage to Turner. He was never captivated by the little church that charmed Francis Kilvert, nor by the high-banked lanes or Baptist chapel that fascinated Eric Ravilious.

His subject was instead the natural essence of Capel-y-ffin, freighted for him with spiritual, mythical and personal meaning. It was the Capel of his mind: a magical, enclosed and all-round space of water, woods and mountains. In his responses to this cherished place, he had redefined himself and become an artist unlike any other.

The devastating blow to Jones’s love affair with Capel-y-ffin was the ending of his love affair with Petra Gill, to whom he had been engaged since 1924. In February 1927 she wrote to him on Caldey to break off their engagement. He tumbled into a depression and couldn’t any longer bring himself to visit Capel, lest he should meet her.

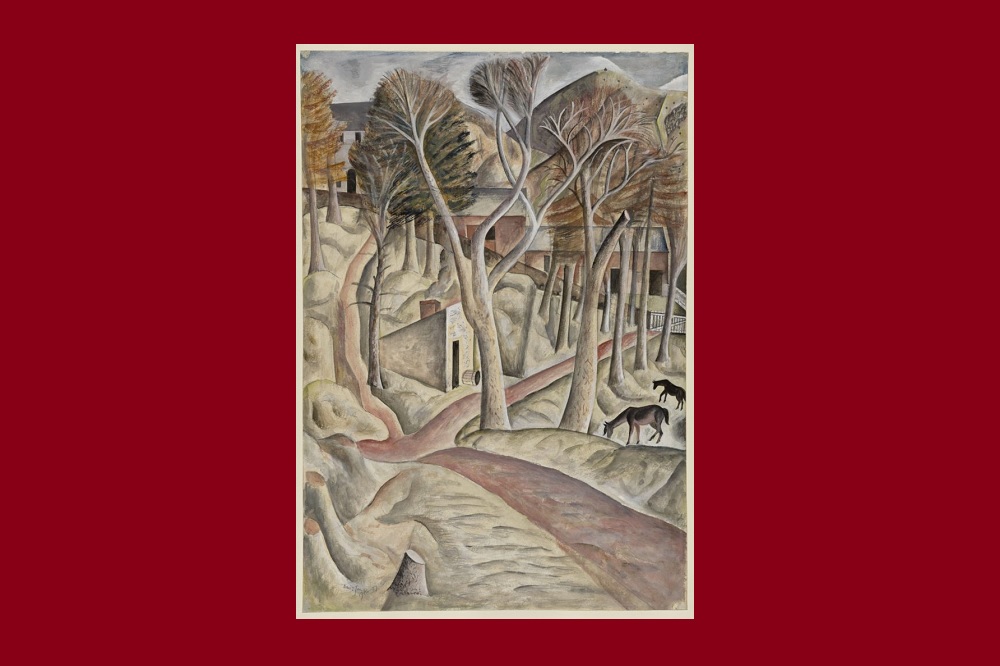

Probably his last painting in the hills was called simply Capel-y-ffin (Amgueddfa Cymru-Museum Wales). Made just weeks before the split with Petra and two years after his first arrival, it was a Christmas gift to the Gill family.

The painting embodies qualities Jones believed were fundamental to his work, including unity, freedom and movement (he said any painting or engraving, ‘has to flow in some way’). It was another stylistic experiment, showing his absorption of ideas from Cézanne and Paul Nash, and one of his most assuredly beautiful paintings.

The view was from the monastery towards the farm, sheltered by winter trees. Paths led on invitingly, ponies grazed, smoke rose from the bake-house chimney; the gate was safely closed. A cut stump and shattered branches might show Mametz Wood ricocheting in the artist’s mind while his beloved mountain, ‘Twmpa’ as he called it, secured the ground after those years in the Somme where there had been, as he wrote in In Parenthesis, ‘no hills to cover us.’

Although he would not return, his work at Capel and on Caldey had transformed his career. He had joined Britain’s leading modernists in the Seven and Five Society, and in 1927 he had his first exhibition – a combined show with Eric Gill. He showed some thirty paintings of Caldey and Capel and sold nearly everything.

In just over two years of his visits to Wales, David Jones had metamorphosed from a wavering student returned from war to one of the leading artists of his generation.

The exhibition Hill-rhythms: David Jones + Capel-y-ffin continues at y Gaer: Brecknock Museum, Art Gallery and Library every day until 29 October 2023, admission free.

This article draws on Peter Wakelin’s book to accompany the exhibition, published by the Brecknock Art Trust and Grey Mare Press.

A free study day to accompany the exhibition takes place on 7 October. Speakers include Peter Wakelin, artists Eleri Mills, Clive Hicks-Jenkins and Kath Littler and poet Frank Olding. A highlight is a Q&A with David Jones’s biographer Tom Dilworth by video from Canada. Booking essential: tickets here.

Catch up with the other articles in this series here

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.