Exhibition: Streic! 84-85 Strike! National Museum, Cardiff

Jon Gower

It was to be a year of tensions and social convulsion: 1984 was the year Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher took on the mining communities.

This important, superbly arranged exhibition charts how a summer of hope and high-spirited defiance led to a winter of violence, hardship, loss of livelihoods – and ultimately life – across some of Wales’ hardiest communities.

Resonant

For its curator Ceri Thompson the strike is a resonant part of his own life. He used to work at the colliery at Cwm and well remembers the strike’s signal votes and the hours manning the picket lines, the hardships felt by many families and the many attendant acts of solidarity.

There was also the fact of ultimately losing his job, which he describes as nothing less than “a bereavement.”

Forty years after the defeat of the miners and all of the consequent challenges for the communities of the former coalfield, the exhibition marshals a fine array of photos and protest placards, fund raising memorabilia and personal stories to evoke the Miners’ Strike and its profound effect on the Welsh nation.

Ceri explains how the exhibition is divided into three parts, the first setting the scene: “A lot of people don’t realise how important coal was to Wales. There are so many villages that only exist because there’s a colliery in the middle of it. In 1921 230,000 men were employed in the coal industry while the peak of production was 60 million tons in 1913, but the peak of employment was 1921. Which is funny because 1921 is the date when it all starts to go down again.”

By the 1970s it was hard to recruit miners to work underground as there were plenty of cleaner and less dangerous jobs available.

Fresh air

Visitors to the exhibition first see a recruitment video made by the National Coal Board which features lots of happy, smiling colliers with remarkably clean faces interspliced with plenty of shots of fresh air, recreational opportunities such as swimming and kayaking.

As Ceri explains there were other pressures on the industry at the time other than alternative, cleaner kinds of jobs: “Oil was coming in, so they had to advertise on TV and in places like the Sun and the Daily Mirror asking for colliers, asking for miners to join the workforce. I don’t know where all the swimming comes into it, or the kayaking but it was to make people want to come into this modern industry rather than this hellhole they were expecting.”

The biggest object in the show is a model of a pithead wheel, the sort of structure you saw everywhere at one time but is now confined to museums such as Big Pit in Blaenavon, where Ceri is the curator.

And some of the most colourful are the lodge and district banners, which Ceri considers to be the equivalent to working class heraldry.

While they are often beautiful works of art in themselves it’s hard not to read the names as a litany of loss, the collieries that were eventually shut down, unleashing the spectre of mass unemployment in their respective communities. Cynheidre. Duffryn Rhondda. Mardy. Oakdale.

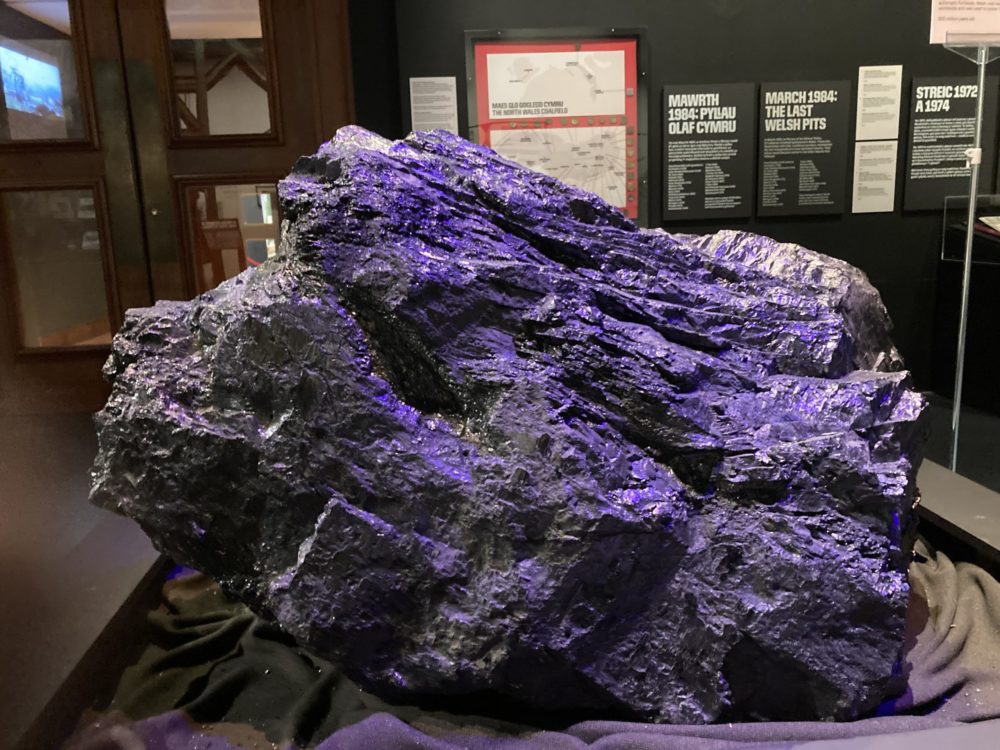

We pause at a humongous piece of coal with a beautiful name. ‘That’s called the peacock’s skin. It’s a large lump of anthracite from Cynheidre colliery which they called the peacock’s skin because it has a purple tinge to it when looked at in the light. And because it’s anthracite it’s rock hard.’

There is one point in the circuit of the exhibition where the visitor is given a choice which way to proceed. ‘So if you went through this way, it was all Emlyn Williams and the NUM in Ponty, no surrender. On the other side you had to walk through with the police and pickets to go to work, didn’t you?’

Julia Greenhaf is one of the gallery staff who meets and greets visitors and is suitably bedecked in miners’ badges. She tells us about the reaction to the exhibition: “It’s been fantastic. We had a group of sixth formers from a Machynlleth school here this morning. One of the boys, his grandfather was actually living down here and was involved in the strike.

“It was so poignant for him to come and see that. We’ve had people from all over: a gentleman from Aberdare, then another from Cemaes Bay. When you’re working on the door, you will get mixed reactions. You will get people saying, oh, it’s very one-sided. But if you go around and you read everything, it is not one-sided. You’ve got to choose, haven’t you, between going one way or the other way. People don’t tend to notice that.”

We pause at an arresting piece of art called “Iron Lady versus Men of Steel.” The artist Doug Jones took a wax head of Margaret Thatcher which had been originally been created by Antony Dufort and introduced workers who seem to be determined to take it apart with their drills. As Jones once explained: “She attacked the Welsh mining industry and the miners are now attacking her.”

One of the most poignant artefacts is a toy doll. Ceri explains “There was a lady called Anne Wyn Morgan who was a local councillor in Merthyr Vale, which is next to Aberfan and she was also a member of the Women’s Support Group. Her main job was working in the bridal department of Marments in Cardiff, which was the oldest department store in the city. She had the idea of going round all the miners on strike and asking, how old is your daughter, how many do you have? So she got a big list of them, bought naked dolls from Marments’ toy department and then used the offcuts from the bridal costumes to clothe dolls for each and every girl.”

If there is one word that sums up this vibrant and informative account of a passionate, turbulent period in Welsh history it is “solidarity.” The sort of solidarity that saw pop musician George Michael as one of the miners’ biggest supporters, along with Freddie Mercury from Queen and bands such as Bronski Beat. The women who stood alongside the men and kept the twin fabrics of family and society together. The Gay and Lesbian groups who raised money together with the many local fundraisers all over Wales and beyond.

It was a solidarity expressed throughout working class communities just as it was by the colliers gathering the ‘black diamonds” underground. As Ceri put it: ’I don’t think I disliked anybody I worked with. You couldn’t dislike somebody when your life depended on them. You used to have a big deployment board with everybody’s name on it. You’d have all sorts of names – Polish, Yugoslavians and Lithuanians, Italians – all sorts of people working together.’

Working together. Living together. Standing strong in unity.

Streic! 84-85 Strike! is at National Museum in Cardiff until the 27th April 2025,10:15am – 4pm. Pay what you can.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.