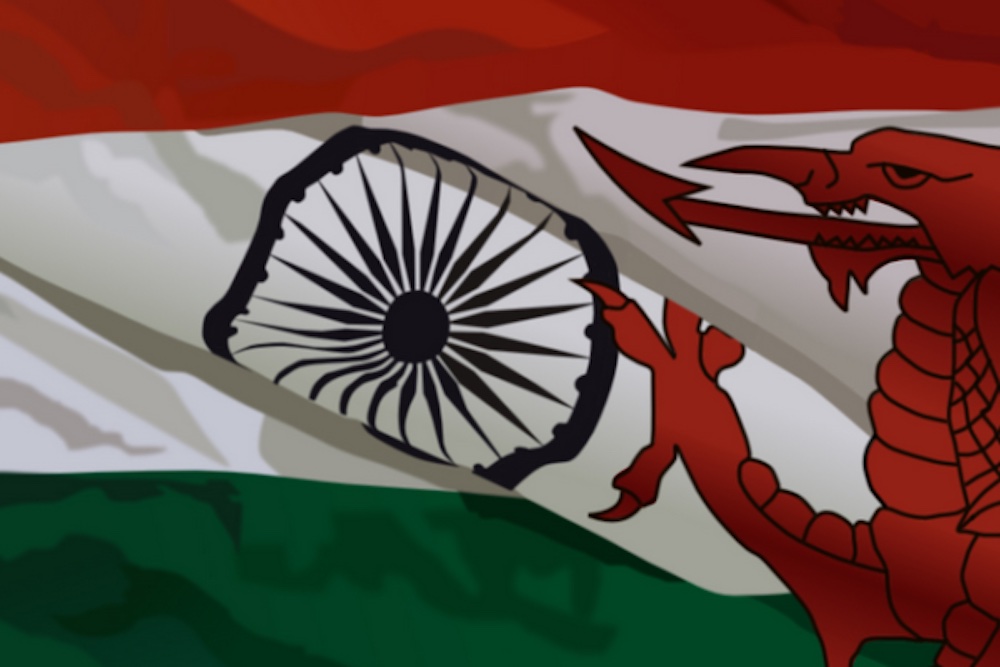

Exploring the history of the Welsh relationship with India

Rhys Owens

Last month in one of his final acts as First Minister, Mark Drakeford launched the Welsh Government’s year of ‘Wales in India’, with aims of ‘strengthening the ties between Wales and India, foster new trade and investment opportunities, champion cultural and sporting connections and cement academic and healthcare collaborations’.

No doubt those who shaped modern, independent India would have been heartened by such a scheme. The early embracing of the Commonwealth of Nations by India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, was premised on its wider symbolic meaning of a

community of equal nations emerging out of the shadow of Britain’s infantilising empire.

The realities of modern global capitalism, in which former imperial centres now turn to powerful independent former colonies not with the firm hand of coercion, but the warm hand of friendship, would no doubt have inspired in Nehru and his colleagues a warm glow of satisfaction, regardless of its deeper motivations.

But for the greater part of the long relationship between Wales and India it has been defined through the framework of Britain’s imperial ambitions. The Welsh were enthusiastic and active participants in the British Empire throughout its history, and no imperial relationship better defines the Welsh perception of empire than its relationship with India.

Early Beginnings with the East India Company

The first major interactions between India and Wales came through the East India Company, a monopoly enterprise established by Royal Charter in 1600 during the final years of Queen Elizabeth I’s reign to explore trade in Asia. Welsh merchants were involved from the early years and, although dwarfed in number by their English, Scottish and Irish counterparts, fortunes

began to flow back to Wales and were used to purchase large estates, especially in Powys and around Brecon, which became a centre of Welsh East India Company networks.

Key figures from this period include Thomas Parry of Welshpool, who established a prominent merchant house in Madras (modern-day Chennai). The Indian company EID Parry still bears his name. Other prominent Welsh ‘nabobs’ were Robert Wynne of Merioneth, Walter Wilkins of Breconshire, and Thomas Jenkins of Cardiganshire.

Indian fortunes also flowed into Wales through that most famous and notorious of East Indiamen, Robert Clive, whose vast wealth was partly used to renovate Powis Castle. But by far the most famous Welsh East Indiamen from this period is the Calcutta (Kolkata) judge and linguist William Jones, who founded the Asiatic Society of Bengal in 1784. Jones is chiefly remembered as a key advocate (though not the first) for the common ancestry of European and Indian languages, and a definite link between Sanskrit and Latin and Greek.

Welsh East Indiamen benefitted from a strong Welsh London network near the centres of power and familial links that supported each other administratively and financially in India itself. However, historians such as Lowri Ann Rees have argued that while St David’s Day was sometimes celebrated among this cohort in India, there is less evidence for a distinctly Welsh identity and even less evidence of the use of the Welsh language.

The Welsh Missionary Movement

The most well-known and enduring image of the Welsh-Indian relationship came in the form of the missionary movement, most notably the Welsh Calvinistic Methodist Mission which operated mainly in the northeast of India, in the modern-day states of Assam, Meghalaya and parts of Bengal which now lie in Bangladesh.

Welsh missionaries first operated in India under the auspices of the London Missionary Society but broke away in the 1840s and sent Thomas Jones as their first missionary to the Khasi people, an event which would eventually see rapid conversions to Christianity and a relationship between the Khasi and Welsh people which endures today in many religious and cultural forms. Indeed Jones, having committed the Khasi language to written form, is still celebrated by many people in the region as the father of the Khasi alphabet and literature.

The Welsh mission field in the northeast was so successful relative to other Indian missions that by the 1920s government officials were dedicating sections of the census returns to analysing the rapid Christianisation of the Khasi and Lushai (modern-day Mizo) Hills. To the Welsh in Wales, the mission field was the enduring image of Wales imperial mission in India, and returning missionaries would speak to packed out chapels and collect vast sums in donations for their ‘civilising mission’ in the northeast.

The Welsh press, especially the Welsh-language press, would focus in on this aspect of Wales’ imperial relationship. The South Wales Star reported on one such missionary meeting in Cadoxton in 1891 in which the speaker, Mr Thomas of Delhi, spoke passionately about the Christian plight against Hindu and Muslim ‘pagans’.

The Welsh missionary movement, which operated in India until the 1960s and by which point was primarily run by women such as Helen Rowlands, represented so much of what it was to be Welsh in the late-nineteenth century- Welsh-speaking, nonconformist and part of a wider British Empire. While it is often thought Wales’ main interaction with imperialism in India, the Welsh also found themselves in a wide variety of secular roles within which their Welsh identity shone brightly.

Welsh Imperialists and St David’s Day in India

In March 1899, the first annual St David’s Day dinner hosted by Cymdeithas Gwladol Cymru yn yr India was held in Calcutta. This event was to become a regular feature of the Calcutta Welsh, though the society fell into hiatus for a few years before being reformed as Cymdeithas Cymry Bengal in 1909. This was the most prominent of several Welsh societies which sprung up

around India between the 1890s and the 1940s, including Bombay (Mumbai), Poona (Pune) and New Delhi. These groups were important spaces of Welsh fellowship and cultural maintenance where the Welsh language was spoken, and the Welsh homeland celebrated.

The 1899 event, attended by 63 guests, included a menu of Welsh broth and leeks and Welsh rarebit. Toasts were made to ‘Ein Frenhines ac Ymherodres’ (Our Queen and Empress), ‘Tywysog Cymru’ (The Prince of Wales), St David and the land of Wales. The band played a series of classic Welsh tunes and the entire company engaged in singing. Presided over by the Welsh Chief Justice of the Bombay and later Calcutta High Court, Sir Lawrence Jenkins, and the prominent Calcutta barrister Sir Griffith Evans, the event represented a key date in British Calcuttan high society.

These societies sought to provide fellowship for the Welsh in India, though during wartime they also acted as key pillars of support for Welsh soldiers far from home. The New Delhi and Poona societies, for example, were formed in 1945 specifically for this purpose, and the Bombay society started life during the final years of the First World War though carried on its activities into the 1930s, partly as a group to support the Welsh Regiment in the Bombay Rugby Cup. The local press would report members of the society attending the games brandishing leeks and saucepans and chanting in a ‘strange tongue’.

These societies counted among their membership senior Welsh figures in the Indian administration and attracted non-Welsh patrons from the very top of British Indian society. Indeed, successive Viceroys attended the gatherings of the Calcutta and New Delhi societies, as well as the commander in chief of India Sir Claude Auchinlek. Among their senior Welsh membership could be counted Sir Archibald Rowlands, the Finance Member of the Indian Government during the Second World War, Sir Roger Thomas, a successful agriculturalist who held positions in the Sindh Government as well as in independent Pakistan, and Sir Evan Meredith Jenkins, the last British governor of Punjab.

They were also spaces in which the Welsh could explore their relationship to empire and imperialism. These gatherings often included speeches which highlighted the Welsh perception of themselves as bilingual nonconformists- excellent language learners, strongly moralistic, with lived experience of being a minority within a larger entity. To these Welsh imperialists, these qualities made them better at governing colonial peoples than their English counterparts. There is little evidence to say how Indians thought of this distinction.

The Welsh in South Asia Post-Partition

The Welsh were few in comparison to their English, Scottish and Irish counterparts, but nonetheless rose to positions of influence in administration, the law and on the mission field. Like most British in India, they largely left in 1947, and give or take a few stragglers like Sir Roger Thomas who continued to work in independent Pakistan, the story of the Welsh in post-

partition South Asia is confined to the Welsh Calvinistic Methodist mission, which continued to

operate until it was handed over to the Lutheran mission in the 1960s.

Today, the influence of Welsh Christianity can be seen in the northeast of India among continuing populations of Welsh-inspired Christian communities, the celebration of Thomas Jones and other Welsh missionaries among the Khasi people, and the influence of Welsh music and culture on indigenous art forms.

There are many aspects of Indian society, politics and culture which were influenced by their long years under the burden of British colonial rule. We must remember the distinctly Welsh forms of this British imperialism and strive to understand the influence of Welsh imperial participation across the countries of the former empire.

Rhys Owens is the author of PhD research which examines Wales’ colonial relationship with India and Welsh conceptions of empire

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Da iawn Rhys, keep going with this.

This the same India that is at his moment buying up Russian oil?

Take a step back until they stop supporting the invaders.

Invaders who are protecting their language and ethnic people in eastern Ukraine! Something the Welsh should know all about. Oh wait, we acquiesced to Englands thuggery. I’d expect England to do the same if our Welsh speaking heartland gained power and started attacking English speakers of English diaspora.

Neither of these comments are helpful or useful, and the second one is based on a blatant lie. While it is true, as the first commentator says, that India is taking advantage of the opportunity to buy cheap Russian oil (and while it is undeniable that that is a bad thing for a number of reasons) there are a large number of other countries doing the same. As for the second comment, it reminds me that some Welsh pro-Stalinists called Gareth Jones a liar after he exposed the Soviet-induced famine in Ukraine. (Information on this in Martin Shipton’s book). The… Read more »

Hogan da, teach the boys some proper history. There are no good guys in the power struggle we call Planet Earth

“Robert Clive, whose vast wealth was partly used to renovate Powis Castle…”

Whose vast stolen wealth…

What relationship? We aren’t a “Country” (according to modern standards) until our flag sits beside those at the UN. That can’t happen until we get out from under the Anglos thumb and Boot!