From militant action to marches, part two: Ant Heald interviews historian and author Wyn Thomas

The first part of this interview can be read here

Ant Heald

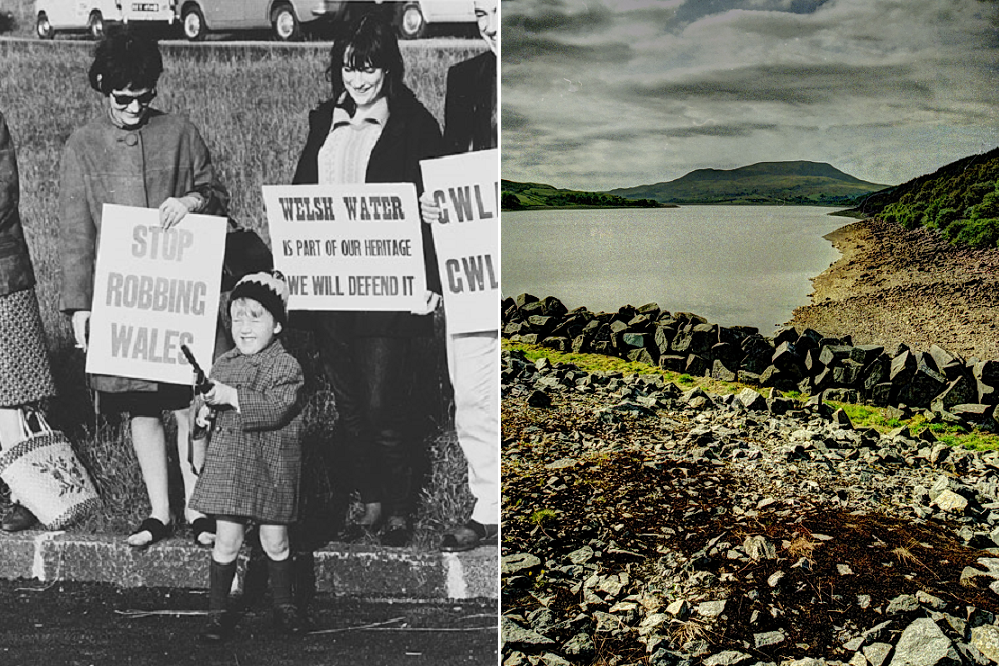

We move on to discuss Tryweryn in more depth, as not only is it the subject of Thomas’s third scholarly book, Tryweryn: New Dawn?, to be published later this year to coincide with the 65th anniversary of the passing of the Tryweryn Reservoir Bill, but it has also become an iconic symbol of the recent resurgence of Welsh nationalism, with countless copies of the ‘Cofiwch Dryweryn’ slogan painted on walls the length and breadth of Wales, as well as on merchandise from bumper stickers to snow-globes. What does this tell us, I wonder, about how history can be used — or misused — to serve social and political causes?

“I think people need to understand the facts,” he states bluntly, “and I can only do it if I cover all sides of the argument. Why did Liverpool need the water? How much were people really opposed to it? Some were probably quietly glad to get out of there and be given new housing. Let’s slow down the rhetoric.

“Symbols matter but underpinning that you have to have a better understanding of what’s going on. Rather than getting swept away on the emotion what I’ve done is looked at it in a more academic detached way, so it’s readable — I’m told it’s engaging — but at the same time the information needs to be correct.

“Any nation that pins its identity on past grievances whether they be 65 years ago or 600 years ago is not healthy; any country which is progressive, innovative, forward looking needs to recognise its history for what it is, rather than wearing it as a badge of inferiority and subjugation. Instead let’s learn the lessons from the past and let’s put Cwm Tryweryn in its correct historical perspective.”

Thomas says that even in advance of the new book’s publication he’s getting hostility online from certain nationalist quarters, because he’s giving the ‘Liverpool perspective’, and anything that might seem to dilute the simplistic demonisation of a rapacious England plundering Wales to satisfy its greed is seen as unwelcome.

“But Liverpool had to take the constitution as they found it,” he insists, “Welsh sensibilities were never going to be enough to stop this from happening. What we can do is look at how much this episode led to devolution, but also how in 2022 are we still not in a position where we have control over Welsh resources?”

Colonial attitude

I suggest that Wales could be looking to its natural resources to place itself at the heart of a global industry in renewable energy technology, but he says he has reservations, coming from a rural farming community, and equates incomers buying cheap housing with beautiful views with buying up farmland to turn into wind farms. “The very beauty of what Wales is, is going to be lost.”

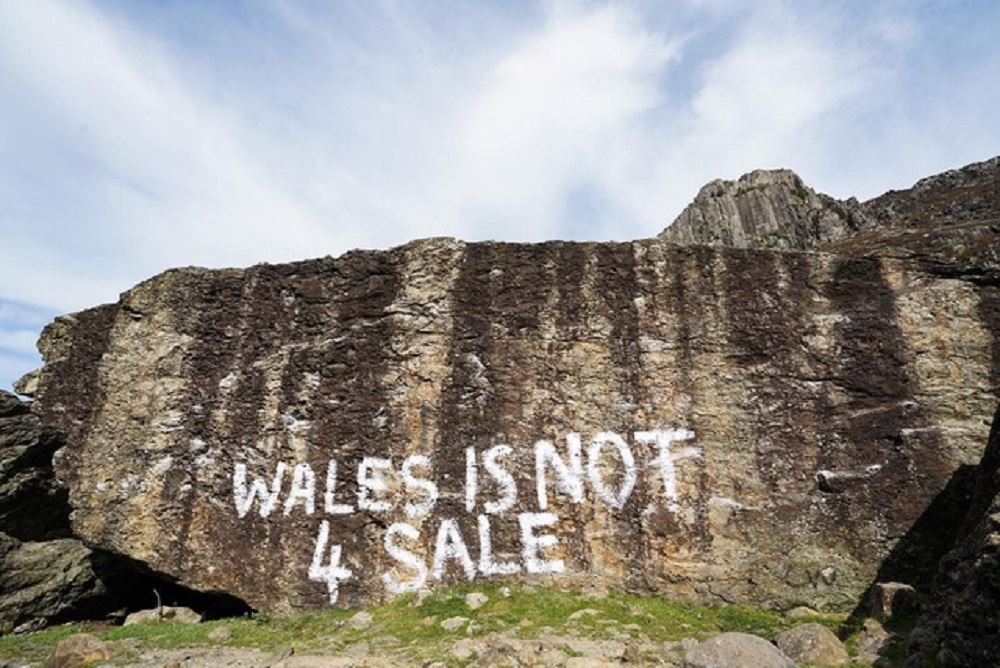

More impactful for him as a slogan than ‘Cofiwch Dryweryn’ is ‘Wales is not for sale.’ “We need to sit round a table and discuss what Wales is. Llanwrtyd, where I now live, is full of people with accents from various parts of England. That’s not part of the social fabric of mid-Wales that I knew growing up.

“What has disappointed me in the past if I’m honest is the attitude of certain — I’ll be brutally honest — English people, who’ve arrived with a very dismissive colonial attitude about Wales, and that is not going to endear themselves to the people they’re living around or working with. There comes a certain point where this is irritating, if not anger inducing.

“And the lesson seems to be ‘we’re only here because it’s cheap’. There’s no respect for Welsh culture. So, it’s a message that everyone has to buy into. Is that fair? Is respect for indigenous Welsh culture a reasonable expectation to have?”

For a moment I wonder if I’m scratching an apparently dispassionate historian and finding a reactionary ethno-nationalist underneath, stuck in a romantic vision of Wales’s past, perhaps not so far removed from some of the militants he has written about, seeking to exclude or assimilate immigrants.

But as if recognising the risk of being misunderstood, he tells me about other English people, such as the producer of the music he has recorded as singer-songwriter, who read his work and as a result said, “I have a lot more respect now for Wales as a nation with a cultural and political identity.”

Dual identity

Then he returns to an anecdote that he had mentioned earlier in our conversation, about attending a concert when his daughter was at school in Newport alongside classmates of Asian, Chinese and Afro-Caribbean origin, all singing folk songs in Welsh.

“And it was beautiful! You take those children with you; you don’t alienate them. Give them a pride in living in Wales, and if they consider themselves to be Welsh, how wonderful! In the John Jenkins autobiography I mention the importance of dual identity, so by all means retain your heritage, but if you adopt into Wales & Welsh culture how can that possibly be bad for Wales or humanity?

“I spent twenty months travelling the world, embracing the culture wherever I happened to be; I have no time for paramilitaries at all having seen the horrors of Northern Ireland. It’s about seeing Wales in a broader context, but at the same time seeing that indigenous cultures are under threat and we have to safeguard our own culture as well. I think there’s a balance: with that comes a responsibility.

“When I came back, I was even more proud; it made me realise how special Wales’s own little place in the world was. It didn’t make me any less respectful of other cultures, in fact it was hugely life enhancing, but so was the lesson learned that Wales is vulnerable and needs to be protected, and this cultural identity — any culture — adds to our global understanding of what life is all about.”

Insularity

He seems to check himself, as if he can’t quite let himself go with such a positive vision without the balance he always strives for in his academic work, and he recalls a memory from his time at school after moving to the more Welsh speaking area of Ammanford from Llandrindod.

“I remember a teacher saying, ‘Yes, he’s alright till he opens his mouth,’ because I had a rural Radnorshire accent and didn’t speak Welsh, and I’ve never forgotten it.

“That’s how insular Wales was at the time: I didn’t like the idea of people moving into Wales and rubbishing Wales, but I can also remember thinking later on, ‘I don’t want to be like her when I grow up.’ I always felt that the insularity of Wales during that period was very unhealthy. So, I’ve always made a point of saying we need to be open and accepting and welcoming. I’m a deeply proud Welshman, but a lot of Welsh parochialism I absolutely struggle with.”

I mention my own experience beginning to learn Welsh and finding that some native speakers are uncomfortable letting me practise speaking Welsh with them. Despite them obviously being much more fluent than I am, they seem to feel their Welsh isn’t ‘good enough’ compared with the ‘book’ Welsh they assume I want to learn, and he suggests, “I think that could be historic actually. There’s a sort of inferiority, a shyness — we need to be more confident as a nation.

“Thank God we voted for devolution because now my children learn about Wales and Welshness; their generation don’t know any different. Cardiff & Newport have become much more Welsh than when I was working there in the 90s. And those children at my daughter’s school singing our folk songs — seeing that was so important to me, and that’s the Wales I want to see.”

Social conscience

Folk songs are also important to Thomas as a performer, with one self-penned album, Chalybeate Spring already released, and another, Orion’s Belt due out later this year, featuring a stellar ensemble of musicians including Van Morrison’s bass player, Pete Hurley; Aled Richards, drummer with Catatonia, and keyboardist Geoff Downes, of Buggles, Yes, and Asia. Folk music was as formative to his development as reading history books.

“Like history, “he says, “folk music is about life. I didn’t engage with the school process, but enjoyed reading at home about the history they didn’t teach us. I learned far more from playing my guitar and listening to Bob Dylan.” It gave him his social conscience, and taught him about the black civil rights movement: “I’ve just been writing about Rosa Parks, in fact.”

I recall that it was from Hands Off Wales that I first learned about Eileen Beasley whose protest and prosecution in the 1950s for refusing to pay her rate demand from Llanelli Borough Council unless it was served in Welsh led to her being regarded as the ‘Rosa Parks of Wales’.

My Llanelli born wife had also never heard of Beasley previously, and I find that many locals in Llanelli are unaware, for example, that Llanelli had the first Welsh medium school to be provided by a local authority.

This leads to us considering the irony that now that Welsh medium education has become so common, for many young people, his daughters included, Welsh has turned from being the language of the street that was banned in the classroom, to becoming a language associated with the classroom, and as soon as they get into the schoolyard they revert to English.

“We need to make the language and the nation attractive,” Thomas asserts, “to make people want to stay and use the language and build the culture and nation.”

We talk about some of the ways this resurgence of national pride is happening, such as the use of Welsh by the Football Association of Wales, and the dragon on the shirt, and how rugby fans often cover the three feathers on their Wales shirts with a leek or a daffodil.

Attitudes are changing, but the focus maybe needs to be more discerning, he says.

Line in the sand

He brings the conversation back to where the story of Hands Off Wales starts, and the focus of his next book: Tryweryn; Welsh water as both a natural resource, and an important symbol of Welsh self-determination: “Why were Welsh people paying more for their water rates than in Birmingham where the water from the Elan valley was going? Why, still, isn’t water devolved?

“It’s not about a nationalist rant, but about providing people with the information they need to better understand their cultural heritage. Protest stems from genuine grievance, but the historian in me feels that burning houses that have stood for 200 years isn’t the answer. And we can’t want a pseudo-fascist identity. Any sympathy I may have had for MAC was tempered by the fact that using explosives, even with all safety precautions, was going to end in disaster.”

As we move towards the end of our conversation we discuss where our line in the sand might be; how do we identify the point where we would have to say that what we hold dear needs fighting for with force and even violence? It’s a question that like most people we find difficult to face, but looking at the erasure of moral boundaries we see in war-torn Ukraine, we’re tempted to think, ‘this couldn’t happen here.’

“But,” says Thomas, “it’s so easy to get dragged into a bloody vortex of mayhem. Look at Northern Ireland; it was the most law-abiding part of the UK, and within six months you had a civil war, so it can happen anywhere.

“I’ve never belonged to a political party. I feel more comfortable on the periphery. As much as I care for humanity, it’s hard not to feel that wherever there are people there are problems. I’d rather do it my own way.

“That’s what I’m trying to do with the book and whether it’s some sort of biblical ‘blessed are the peacemakers’ thing, I don’t know, but I bought into that as a kid. You’ve got a responsibility to stop these things from happening. It’s got to be done with dignity, and with care and attention.”

Meticulous

There is no doubt of the lavish care and attention poured into the thirteen years of interviews, research and writing before Hands off Wales was first published in 2013, and I look forward to reading Tryweryn: New Dawn?, of which Thomas says, “I have exhausted all the sources,” having gained interviews from people who, on the strength of his earlier work, have said “I’ll talk to you, but not anyone else.”

We see around the world all too vividly, as in Putin’s vision of a ‘greater Russia’ the danger of populist nation-building on the basis of false or skewed history.

The meticulous uncovering of significant events in Wales’s history that is Wyn Thomas’s mission may not have such global resonance, but it may act as both a corrective to misconceptions of Wales’s past, and a platform for building a Wales that knows the strengths and weaknesses of its heritage and is open to embracing a confident and inclusive future.

“All you can do as an individual,” concludes Thomas, “is your own little bit to bring about the Wales that you want.”

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

The year is 2022 and we in Wales still do not have any control over our massive resources we have been robbed of all the the natural resources we have had in the past and we should have been one of the welthiest country in the world. if only we were in charge of of our own country and it’s still going on today.We can’t even celebrate St David Day without the permission from the English government.The only hope Wales has got is too start teaching the Welsh children the True history of Wales and then they will fight for… Read more »

“Any nation that pins its identity on past grievances whether they be 65 years ago or 600 years ago is not healthy; any country which is progressive, innovative, forward looking needs to recognise its history for what it is, rather than wearing it as a badge of inferiority and subjugation. Instead let’s learn the lessons from the past and let’s put Cwm Tryweryn in its correct historical perspective.” That would be a hell of a lot easier if we were independent and all the exploitation stopped, just like it happened with Ireland. We can’t be at peace with our history if… Read more »

Who thinks there is no exploitation in Ireland?

Ydynt yn cael eu hecsbloetio gan wladychwyr Saes?

The drowning of Tryweryn and other Welsh valleys in Mid & North Wales was a deplorable act done by the fascist British state on a defenceless Welsh community who were powerless to act against their English aggressor. In effect what was done to Wales was an act of war. Unionists often say how Westminster is a “Democracy” and the “Mother of all Parliaments”, lol. But I disagree. No democracy willingly cleanses a people from their own land to supply England with water whilst ignoring not only villagers pleas but all but one of their elected political representatives at Westminster. Remember… Read more »