From the vaults: The man who wouldn’t stand for Stalin

A word on the novels of Lewis Jones by Hywel Francis

Some notable Welsh public figures were once asked to choose their heroes and give a radio lecture about them.

The writer Gwyn Thomas chose Lewis Jones, a seemingly long-forgotten leader of the Rhondda’s unemployed.

Gwyn talked memorably about Lewis’ refusal to jump through other people’s hoops. All the time I puzzled over the phrase and what Gwyn intended it to mean – for Lewis.

Having been brought up in a ‘communist’ family I was not unfamiliar with the facts of Lewis Jones’ remarkable life: Labour college student, imprisoned in 1926, Cambrian Colliery checkweighman, victimised union activist, leader of several hunger marches, remarkable orator, Communist councillor and proletarian novelist.

He was even capable of holding an audience of over a thousand people for two and a half hours with his lecture ‘The Social Significance of Sin’.

All that was packed into a life of just forty-two years. He died in 1939 on the day that he had addressed over thirty meetings in support of the besieged Spanish Republic. To many he was a hero and a martyr.

Stalin arrives

At about the same time as I heard Gwyn Thomas’ radio broadcast I spoke to Billy Griffiths, close friend and comrade of Lewis, who had served in the International Brigades in Spain.

Imagine, he suggested, the British Communist leader Harry Pollitt coming into Judge’s Hall, Tonypandy.

The packed hall would of course stand in respect. Imagine, then, he said, attending the Seventh World Congress of the Communist International in Moscow in 1935. Stalin arrives. The thousands in attendance rise.

Everyone except Lewis, who was one of the small band of British delegates. He was sent home in disgrace and disciplined by the British Communist Party.

Some say he was overwhelmed with emotion and could not rise; others said he was too busy reading a novel or a comic and could not be bothered.

I prefer to accept a further explanation: he did not believe in the cult of personality and believed that no one should be worshipped, least of all Stalin.

Some say he was capable of all three responses. Take your own pick. Certainly, for me, the deeper reason and how Lewis manifested it fits best.

He was a maverick in the best sense of the word. Born illegitimate, he was shaped by riotous and cosmopolitan Tonypandy.

He married young, enjoyed the company of men and women, could never be a party ‘apparatchik’ and would never jump through other people’s hoops.

His was a discordant revolutionary voice like that of Federico Garcia Lorca, Aneurin Bevan and Antonio Gramsci.

Vividly described

I still remember sitting with Billy Griffiths in his home in Dunraven Street, Tonypandy in November 1969, in the very room where Communist Party meetings took place in the 1930s – meetings that are so vividly described in Lewis’ two novels.

Billy Griffiths spoke with difficulty, as he was suffering badly from emphysema. Among all the interviews I did as an historian, his description of Lewis Jones remains the most powerful evocation of one man’s purpose in life, and it explains why Lewis Jones the novelist is important to us today:

“His main quality I think was love of people and compassion, it superseded everything else. I have seen Lewis… sitting down listening to two old people telling him about their troubles, and tears running down his cheeks. That’s the kind of man he was, he felt it, it was for him more than logic. The rules that could do nothing for these people had to be broken, understand? … .

“I remember recruiting people, we had a meeting here for some people to go to Spain. We used to have a long table here and Lewis sat in by there, by the fire, and I was trying to interest people to go to Spain… .

“And when they had gone out, Lewis got up in the end, he couldn’t stand it any more, he said: ‘You’ve no right, to do that, to get the young boys to go there and die…’ You see it was more important than the politics, [it] was the humanism and compassion… it was this that people loved about him… .”

His powerfully evocative speeches painted such vivid pictures of his people’s individual and collective struggles it was thought that he would make a natural novelist. That was the view of Arthur Horner, the President of the South Wales Miners’ Federation.

Lewis acknowledged this in his foreword to Cwmardy, referring to Horner as ‘my friend and comrade… whose fertile brain conceived the idea that I should write it’.

According to Lewis, Arthur Horner ‘suggested that the full meaning of life in the Welsh mining areas could be expressed for the general reader more truthfully and vividly if treated imaginatively’.

The ‘people’s remembrancer’

And that, expressed in Lewis’ own words, is the essence of both the work and the man for us today. He was the ‘people’s remembrancer’ who had also contributed actively to the people’s chronicle.

In that sense Lewis Jones is unique in the political culture of Wales in the twentieth century, standing alongside only Saunders Lewis (and what an intriguing contrast) in combining political activism with literary aspirations and, indeed, with literary achievement.

The difference between the two, however, was that Lewis Jones was directly of the Welsh working class and gave voice to their pain and suffering.

For that reason he stands apart from all other activists and writers in that remarkable generation of self-educated working class men and women, the organic intellectuals who provided local and national leadership for communities broken by economic depression.

He was the organic intellectual of the South Wales valleys in the inter-war period.

Friends and comrades

I suppose the people in Cwmardy and We Live have resonance for me because I feel I knew many of them. Big Jim, Len, Siân were an amalgam of many of Lewis’ friends.

I knew them too – albeit a generation later. Jack Jones, the Rhondda miners’ agent, and Will Paynter, later general secretary of the NUM, were both International Brigaders, and frequent visitors to our home.

Mavis Llewellyn and Annie Powell, schoolteachers and councillors both, were also well known to me because they too were my father’s ‘friends and comrades’. They all come alive again when I read Lewis’ two novels.

My first acquaintance with the novels, in the late 1960s, occurred when I was beginning my research into the Welshmen who fought fascism in Spain by joining the International Brigades.

It was at this time I met Dai Smith. We read the books at the same time. Fresh from New York, he was hoping for a Joseph Conrad; I was looking for a Will Paynter. The characters for him were somewhat stereotyped; for me they were ‘flesh and blood’.

The only conversation which compares with the one I had with Billy Griffiths in 1969 was one I had with Mavis Llewellyn in 1972. Lewis and Mavis had been ‘close’ in a way that was a problem in the puritanical communist world of the South Wales valleys in the 1930s.

Mavis explained to me that when Lewis died, We Live was incomplete. The last two chapters – ‘A Party Decision’ and ‘A Letter from Spain’ – were essentially hers, and that is why the voice is softer, more poignant, more reflective.

The description of the relationship between Mary and Len is a description of their own relationship.

Pressures and sacrifices

When in the 1970s and 1980s I wrote about the political pressures and sacrifices of those who went to Spain, and argued that there was an ‘inner party conscription’, my research was disputed by some in the Communist Party, but the survivors from Spain only needed to point to their tribune, Lewis Jones, for confirmation of that truth, and for confirmation of the deep and troubled circumstances that had made it true.

‘The full meaning of life’ is surely given in these novels.

I agree with Gwyn Thomas’ words to me on the occasion of a Llafur Day School in the Rhondda which first re-launched the novels back in 1978: ‘Any residual dust left from the passing of that astonishing star should be cherished.’ Cult of the personality? Read the books and judge for yourself.

Cwmardy is now available again the Library of Wales series.

The People

Hywel Francis

Hywel Francis was the Labour Member of Parliament for Aberavon between 2001 and 2015. He was formerly Professor of Adult Continuing Education at the University of Wales, Swansea. Amongst his publications is the classic Miners Against Fascism (1984).

His father, Dai Francis (1911-1981), was General Secretary of the National Union of Mineworkers (South Wales Area). He died in 2021

Lewis Jones was a man of his time, an autodidact, like many in the factories and mines. He was a union organiser and gifted public orator He wrote the Cwmardy sequence to directly inspire the working-class people he was part of.

He died in 1939 of a heart attack on a day he made over thirty speeches in one day. We Live was unfinished at the time of his death and was completed by his close friend and fellow activist Mavis Llewellyn.

Mavis Llewellyn

Welsh-speaking Councillor Mavis Llewellyn, of Nantymoel, Ogmore Vale, in South Wales, was an “orator almost unparalleled among the women of Britain”.

She had been elected to the Ogmore and Garw Urban District Council, at the third time of trying in 1936, when “she was returned with a bigger majority than the total poll of her opponent.” The final tender chapters of the novel, We Live “A Party Decision” and “A Letter from Spain” were written by her.

In later life, Mavis Llewellyn lived at 47 Commercial Street, Nantymoel, near Bridgend. South Wales. She was also a candidate in the 1950 general election for the Party.

For more information see Graham Stevenson’s fascinating encyclopedia of Britsh communist biographies.

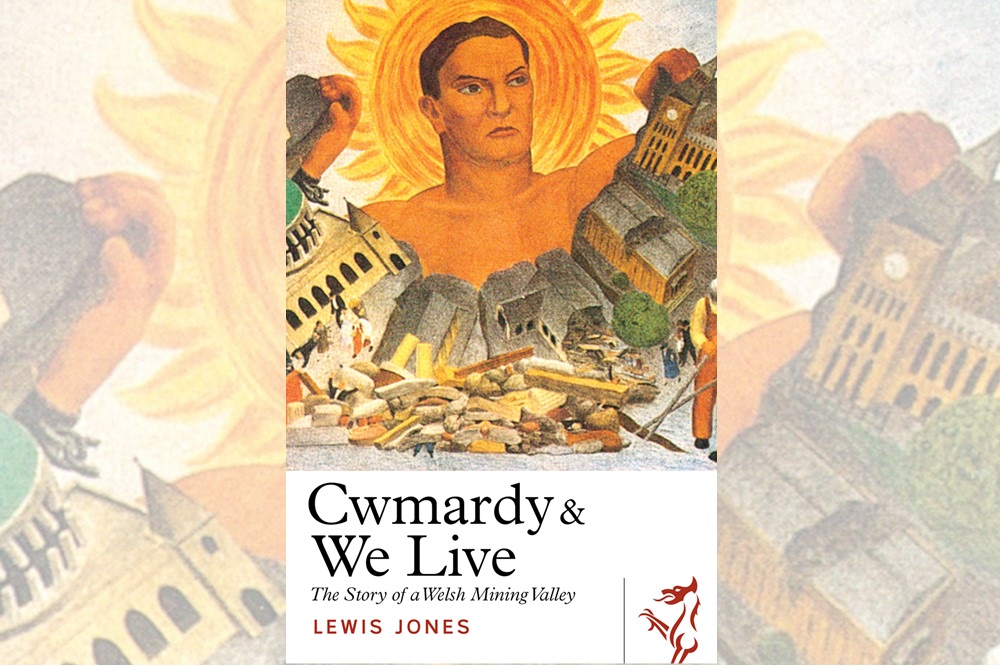

The cover of Cwmardy/We Live is The Coming Revolution (1935) from a fresco by Jack Hastings, by kind permission of the Marx Memorial Library

Jack Hastings, or Francis John Clarence Westenra Plantagenet Hastings, fifteenth Earl of Huntingdon (1901- 1990), was trained at the Slade School of Art. He painted many murals worldwide, including one at the Chicago World Fair in 1933, and worked as an assistant to Diego Rivera in San Francisco.

Hastings took his seat in the House of Lords and served as a Parliamentary Secretary in the Labour Government between 1945 and 1950. He also taught at Camberwell and Central Schools of Art and served as chair of the Society of Mural Painters from 1951 to 1959.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Great article, will be getting the books