‘Go to bed in Swansea, wake up in Paris’: The story of Wales’ forgotten sleeper train to France

Luke James

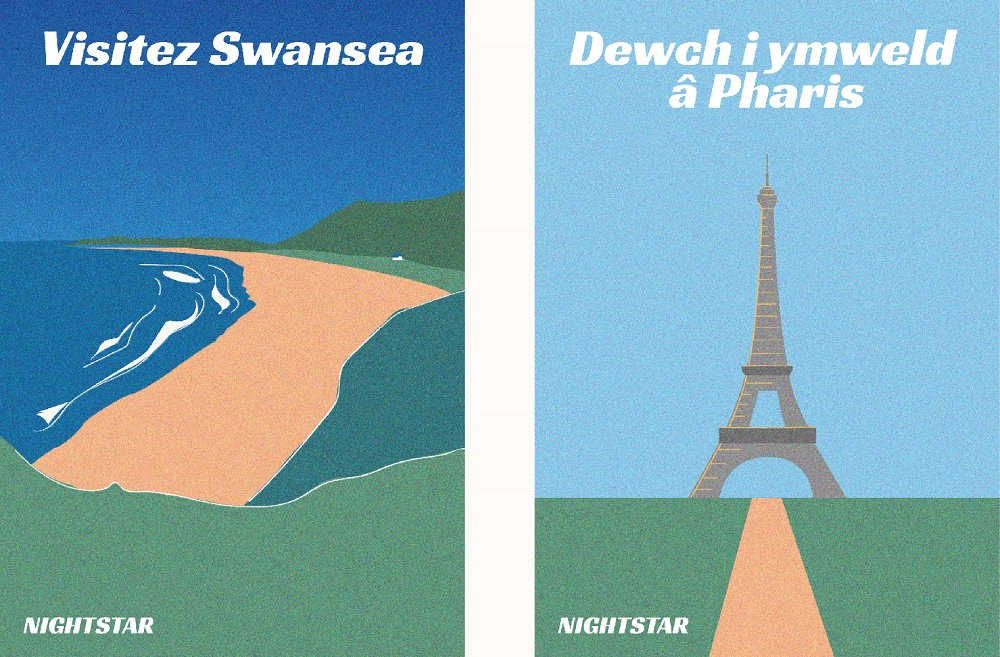

Illustrations by Neus Gonzalez Icart

The sun has just set behind Mumbles Pier as passengers with suitcases scan the departure board at Swansea station. Between the final services to Carmarthen, Pembroke Dock and Paddington, appears the 9.15 to Paris.

With passport checks carried out on board, passengers head straight to the platform where staff speaking in gallic lilts direct them to one of the seven turquoise and green carriages where they will spend the night.

Those on a budget try to get comfortable in reclining seats as they wait for the trolley service. In the other half of the train, some settle down in bed with a book or a copy of the Evening Post, others head to the lounge car for a night cap, and those who have paid most enjoy a warm shower.

After stops in Cardiff, Newport and Bristol, only a good night’s sleep and the city of light await.

At a time when underfunding has made some rail journeys within our borders difficult enough, such a scene playing out at a Welsh train station seems as fictitious as the sleeper train-inspired novels it brings to mind.

Yet it was to be a daily occurrence from May 1994 under plans for the ‘Nightstar’.

“A new generation of international hotel trains, revolutionising long distance overnight travel in Europe,” promised promotional material. “Go to bed in Plymouth or Swansea and wake up in Paris.”

As the renaissance of the night train gathers pace this week with the launch of the ‘European Sleeper’ between Brussels and Berlin, Nation.Cymru has taken a trip through the archives to bring you the story of Wales’ own wagons-lit.

The Channel Tunnel

It’s a tale that begins in 1986 at Canterbury Cathedral, with Margaret Thatcher and French president François Mitterrand signing an agreement to construct the Channel Tunnel – a project that would “change the lives of people on both sides of the Channel”, Thatcher promised.

But even before digging began, there were fears this would be another expensive infrastructure project which brought little benefit outside London.

The late Paul Flynn MP warned the tunnel could lead to a “further deepening of the east-west divide between the claustrophic, overheated and overcrowded south-east of England and the vast acres of opportunity in Wales and the west of England.”

The same fears were expressed in Scotland and the north of England, eventually forcing the government to include a clause in the Channel Tunnel Act requiring British Rail to ensure international services reached “various parts of the United Kingdom.”

British Rail began drawing up plans to run day time services beyond London.

“There was a lot of high level politics behind it quite a long way back,” said John Prideaux, the former director of British Rail’s InterCity services, of the Regional Eurostar project.

“My preferred approach, which was not the approach which was used because politically it didn’t sound so good, was to try and make sure that it was as easy as possible for people from a whole range of places to get by normal services to join the Channel Tunnel trains in London.

“It was a political preference that people wanted to stay that this investment in the Channel Tunnel will benefit as much of Britain as possible.”

Wales though was still set to miss out for a familiar reason.

As a 1986 British Rail memo stated: “Such services will, by necessity, be limited to the electrified main line routes.”

While planned ‘Regional Eurostar’ services to Scotland and the north of England would have cut journey times for passengers in north Wales, electrification wouldn’t reach Cardiff for another 34 years and the rest of the Great Western Mainline to Swansea remains without electrification today.

That added insult to injury already sustained under Thatcher’s government, which changed the guiding principle of British Rail away from the concept of the “social railway” to one based on cold, hard numbers.

The Department for Transport “recognise no special ‘Welsh dimension’, this puts us under considerable pressure to manage solely on the basis of financial performance,” states one British Rail document from 1983.

On top of a refusal to electrify Welsh lines, this strategy saw the cancellation of Wales’ last remaining night services which ran between Fishguard and London Paddington and between Holyhead and London Euston.

Against this background, politicians pressed the case for a Welsh connection to the continent.

In a 1988 meeting about the “effects of the Channel Tunnel on Wales”, Secretary of State for Wales, Peter Walker told British Rail that “the Cardiff governmental and business community fear they may be isolated in the absence of through electric services.”

“Either alternative, via London (Underground) or Reading and Ashford seems unattractive”, he added.

Speaking in the Commons, former shadow Secretary of State for Wales, Denzil Davies, set out the “concern that no attempt is being made to provide a direct and speedy link from south-west Wales to the Channel tunnel.”

In response to Welsh lobbying, in public and private, British Rail eventually proposed two solutions.

First, a twice-daily Intercity service between Swansea and London Waterloo, the original UK terminus for Eurostar trains.

The route, which Transport minister turned TV rail traveller Michael Portillo said would be “envied by other people”, meant that, unlike now, passengers travelling to the continent from south Wales during the daytime wouldn’t need to haul their luggage across London after arriving in Paddington.

The second solution was what would become known as the ‘Nightstar’.

Plans for a “night service from Swansea, Cardiff and Newport to Paris, Brussels and beyond” were included in a glossy brochure published by British Rail in 1989 to outline its international ambitions.

“Current studies indicate that there is demand for two night services to and from Scotland and one to and from the West of England and South Wales,” it explained.

“On mainland Europe these trains will divide so that both Paris and Brussels are served, the Brussels train continuing to Cologne and Amsterdam.”

Crucially for south Wales, it added: “These trains will be able to serve places which are not part of the BR electrified network since electric and diesel locomotives can be interchanged en route.”

But British Rail’s plans for the Eurostar to go beyond London had already hit trouble by 1991.

Political storm

Despite British Rail memos warning of a “major political storm” in the case of cancellation, dark forecasts about their commercial viability hung over their future.

They also met resistance from British Rail’s sister companies in France, Belgium and the Netherlands, with the Dutch in particular singling out the Swansea to Paris route for criticism.

“The wrong routes were chosen,” Hans Hanenbergh, who represented Dutch rail company NS in negotiations with British Rail, later told the Gazet van Antwerpen newspaper.

“The British demanded that Scotland, Wales and South West England have through connections with the continent. I see no all year market between Paris and Swansea, for example. I repeatedly expressed my doubts.”

One Welsh transport consultant agreed, warning on HTV Wales News that most passengers on the Paris to Swansea service “won’t bother coming to Wales but will stop off In London instead.”

The French and Belgians too “have never been very enthusiastic about North of London trains”, British Rail admitted internally.

However, they would be “more enthusiastic about night services through the Channel Tunnel if we were not to go ahead with the day trains north of London, as they see a market overlap,” the memo added.

Ahead of a crucial meeting with the chairman of France’s SNCF rail company in Edinburgh, British Rail leaders agreed: “If we had to choose between the two, our priority would be to implement Night Services.”

All parties were eventually brought on board, however reluctantly, with a promise that British Rail would foot the bill for services running past London.

The dream began to be turned into a reality as British Rail published detailed plans for the Nightstar.

A draft timetable was produced and rail expert Professor Stuart Cole recalls “a senior person in Eurostar asking me about Welsh language policy on the railways.”

The service was to leave Swansea at 9.15pm, enter the Channel Tunnel around 4.15am, emerge in France at 5.15 and arrive at Paris Nord exactly 11 hours later.

That includes a potentially sleep-shattering stop at London’s Kensington Olympia, where the carriages from Swansea would have been noisily shunted together with another seven carriages originating from Glasgow.

The diesel locomotive needed to run on Welsh tracks would also have been swapped for an electric model fit for the Channel Tunnel.

Later timetables suggest a departure from Swansea between 7pm and 8pm, while proposed departure times for the return journey from Paris vary from 10.15pm to as late as 11.30pm.

Potential calling points within Wales differ too. While most timetables mention only Cardiff and Newport, one version includes Neath, Port Talbot, Bridgend.

Earlier suggestions of a connection from south Wales to “Brussels and beyond” also disappear from view.

While there were still details to be ironed out, the Nightstar appeared on track when, in 1992, a £120 million order was placed for 139 carriages.

The majority were the sleeping carriages designed to attract business travellers and “comfort-seeking leisure travellers” by offering, as one brochure promised, “service quality and facilities akin to those of a good hotel.”

If the Swansea to Paris service had left at the earlier time, it’s likely these passengers would have boarded to find their cabins set up in day mode, with the two bunk beds converted into a settee and table on which they would be served their complimentary welcome drink and breakfast the following morning.

Later, staff would have come to make-up the beds for the night with sheets, a duvet and a pillow.

Each carriage would contain ten cabins, all including a wash basin, wardrobe, facilities for making hot drinks and a phone with which to order room service.

Six of the ten were also to have an en-suite shower room “similar to that found on yachts.”

These services were expected to cost “similar prices to club and economy tickets on airlines”, according to a draft pricing policy published by European Passenger Services.

On the other half of the train were three carriages each containing 50 seats designed for “leisure travellers with more modest budgets.”

They would be banned from entering the lounge car which separated sleeping and seated accommodation, except to buy snacks from a dedicated counter once the trolley service had stopped for the night.

“Generous leg space”, an overhead locker and “generous provision of toilet and washing facilities” were the only concessions to the comfort of these passengers.

They at least would have been spared the long queues which Eurostar customers face today.

Plans were made for “immigration formalities” and customs controls to be carried out on board trains at the insistence of the French national rail company, SNCF, which estimated that a 15 minute wait for passport checks before boarding would cost them 1 million passengers a year.

“Every effort must be agreed to cause the habits of the British administration to evolve towards practices which are generalised on the continent, even at the frontier between the Federal Republic of Germany and the German Democratic Republic,” reads notes from a meeting between SNCF and British Rail management in 1987.

Railway managers were hopeful the process of European integration taking place at the time would have saved them from installing immigration and customs controls at stations like Swansea or making passengers leave their beds for late night checks.

However, the European Union also presented an obstruction on the tracks.

Anti-monopoly laws

Plans to create a company, European Night Services (ENS), to run the Nightstar on behalf of the national rail operators of the five countries involved fell foul of the EU’s anti-monopoly rules.

The Commission agreed to an exemption – but only for a period of 10 years and on the condition that British Rail and its continental partners grant any other interested transport operator the means to run a rival service through the Channel Tunnel.

That began a legal dispute that was only settled by the European Court of Justice after plans for the ‘Nightstar’ had hit the buffers.

The issue remains sufficiently sensitive today for the European Commission to have refused a freedom of information request from Nation.Cymru for documents connected to the case.

In keeping with popular myth about British Rail, the scheduled departure of the Nightstar was repeatedly delayed.

The “aspiration” of a May 1994 start became a vague “from 1995/1996” and then a speculative “from mid-1996”.

In his book ‘Night Trains: the Rise and Fall of the Sleeper’, Andrew Martin writes: “I travelled on Eurostar on the second day of its operation. It was November 1994…I picked up a leaflet headlined ‘What Next?’ which boasted: ‘In early 1997 night trains will be introduced, travelling from Scotland, the North West, South Wales and the West into Paris.”

But by the time 1997 came around, the Nightstar was being branded the “rail flop of the century.”

“People had rather exaggerated the potential demand for rail travel through the Channel Tunnel,” remembers John Prideaux, who is now chairman of the Festiniog Railway Company.

“It was a real challenge to forecast the demand but the demand was less than people had hoped for and built the trains for.”

Although one academic obituary of the Nightstar suggested “uncertainty may have eroded any potential markets” and that “the early and confident development of regional services might have stimulated demand.”

The repeated delays to the expansion of European rail services coincided with the start of a new era for air travel in Europe thanks to the liberalisation of sector by the EU.

Low-cost airlines

“The arrival of low-cost airlines in 1995 completely destroyed the business model,” said rail expert Mark Smith, better known as ‘the Man in Seat 61’.

Between 1991 and 1996, the was a 95% increase in passengers travelling through Cardiff Airport.

The privatisation of British Rail, including European Passenger Services, under John Major’s government dealt another blow to the scheme.

Like Wales’ other sleeper services, the Nightstar was deemed insufficiently profitable. It also created practical problems.

“It fell into disarray when privatization came,” said Professor Stuart Cole. “British Rail didn’t exist anymore so the companies on the other side of the channel said if there’s no BR, who’s going to do the work?”

The Nightstar did eventually reach south Wales in 2001, but only in order to be shipped from Newport Docks to Canada where the 139 carriages are still in use between Montreal and Halifax.

It’s a wound that has never fully healed.

“Look at what we could have had,” wrote Eurostar train manager Justin Perkins on Twitter recently alongside a photo of the Nightstar route.

Ditched

Gavin Newlands, the SNP’s transport spokesperson at Westminster, told MPs the “trains promised to Scotland, Wales and the north of England” were “quietly ditched when no longer needed for political cover.”

Could the comeback of the night train on the continent help wake the Nightstar project from its three decade slumber?

Not on a commercial basis at least, thinks Mark Smith.

“There won’t be any sleepers through the Tunnel now unless something pretty immutable changes – such as governments willing to subsidise night trains, or remove all border/security requirements for trains through the Tunnel”, said Smith, who travelled on the first Brussels to Berlin sleeper service yesterday.

“That’s because the economics of night trains are the most difficult to make work commercially of all long-distance train types.

“Austrian Railways ÖBB have proved it can be done, with a modest surplus, without Tunnel access charges, HS1 access charges and Tunnel security and UK border costs. It can’t be done commercially with those costs added. End of.”

Even core Eurostar services are struggling, forcing a cut to the number of stops made by trains.

So, the Nightstar looks set to remain a dream. But, at a time when Wales is being denied its £5 billion share of HS2 funding, it’s one that shows what could be achieved when the political will exists for Wales to have the best.

As the words engraved at the entrance to Swansea train station say: Ambition is critical.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

It’s been delayed as long as the Russian landing on Mars.

“Even core Eurostar services are struggling, forcing a cut to the number of stops made by trains.”

Primarily due to the expansion in business meetings over Zoom / Teams due to the pandemic and Brexit! We travelled on Eurostar recently, using a mid-day service and arrived in good time, so we got through security easily but it was obvious that having 2 manual passport checks slows things up quite considerably.

Fancy that the Austrian rail company ÖBB should turn out to be state-owned. Fancy that its wikipedia entry should state:

“Eurobarometer surveys conducted in 2018 showed that satisfaction levels of Austrian rail passengers are among the highest in the European Union when it comes to punctuality, reliability and frequency of trains.”

I guess it’s possible to do this in Austria because its so flat and its population so evenly distributed. Oh wait.

Rail services in UK are a discrace with this government while Europe gone forward UK lacks support, we seen plans on rail services in to europe Glasgow Manchester Swansea to Paris and behind scraped by the Government with all the stock that was built sent to Canada, this government cannot run a Sunday service to Royston Varsey in Lincolnshire more is spent on roads putting people on the road and increase in air travel so UK cutting on emissions don’t think so.

There’s a big move on the continent towards more sleeper services. This idea could return.

A high speed passenger catamaran departing Dublin at 5pm connecting with the 6pm sleeper at Holyhead which arrives into Cardiff at 10pm before traveling overnight to Paris might get EU support.