Heading West

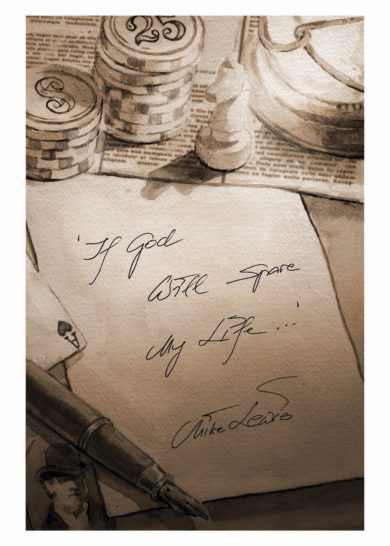

Mike Lewis

The Cardigan-based author of the historical novel ‘If God Will Spare My Life…’ recounts his quest for Will James, the elusive Welsh bluecoat who fought at Custer’s Last Stand.

The squally Montana rain could have come straight from Pembrokeshire.

Over on the ridge to my left a coyote howls.

As I plod tentatively down Deep Ravine Trail from Custer Ridge my fellow tourists have sought refuge in the visitor centre and I have the Little Bighorn battlefield all to myself.

Or do I?

As I lean into the biting prairie wind I cannot escape the nagging feeling I am not alone.

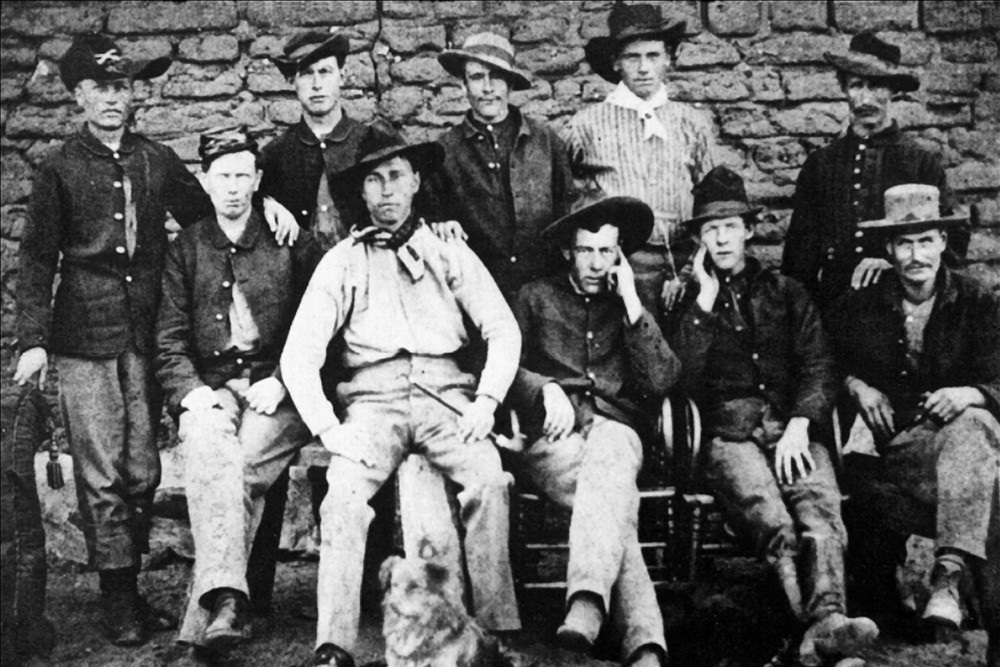

All battlefields have their ghosts and these undulating grasslands in the depths of the Montana wilderness – scene of the most iconic battle of the American West – possess more than most.

For it was here, on Sunday, June 25 1876, that massed warriors of the Lakota Sioux and Cheyenne and other tribes achieved the greatest-ever victory over US federal troops by Native Americans.

By the end of that red Sabbath all 210 soldiers of five companies of the US Seventh Cavalry who had followed Lieut-Col George Armstrong Custer into the valley of the Little Bighorn lay dead – and one of them was a farmer’s son from Pembrokeshire.

News of Chief Sitting Bull’s annihilation of the elite regiment broke like a thunderclap – ‘Custer’s Last Stand’ was the 9/11 of its day.

Big Sky State

Today Montana remains unmistakably Montana – ‘The Big Sky’ state. ‘You are now entering Beef Country’ proudly proclaims a huge banner as I cross the state border from Wyoming.

In the run-up to the 2016 Presidential election, there is little doubt who most Montanians prefer. “I don’t dig that Trump guy,” a teenage waitress confides. “But he’s pro-life and pro-guns so I’ll be votin’ for him.”

Breakfast reminds this Welsh visitor just how far he is from home. I boldly opt for the biscuits and gravy (“food for ridin’ the range, sir”) and let’s just say it was NOT what I was expecting.

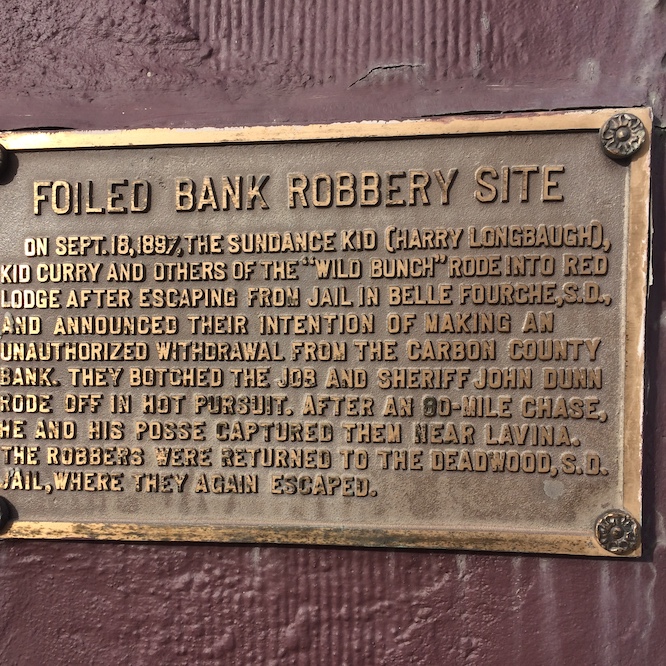

Red Lodge – my base of operations – remains a frontier town.

Cars may have replaced horses, but the place has barely changed since the day in 1897 when The Sundance Kid rode into town to raid the bank – or to make ‘an ‘unauthorised withdrawal’ as a commemorative plaque puts it – only to be hunted down by a makeshift posse.

A trip to the Little Bighorn Battlefield offers a sobering insight into the Native American tragedy.

Those one-time killing fields now lie largely within a Crow Indian reservation – the Crows being among the handful of tribes who fought alongside Custer.

A sign imploring locals to ‘Teach your kids Crow’ struck a poignant chord given current concerns about the falling number of Welsh speakers in my native Ceredigion.

The years have not been kind to these once-proud peoples. Most Crow families live in trailer homes in much-reduced circumstances. A few eke out a living by working in local cafes.

An ornate memorial garden commemorates those warriors who inflicted a crushing defeat on Custer’s troops, the consequences of which reverberate to this day.

Although a memorial to US Seventh Cavalry horses preceded this Native American shrine by a couple of decades, it is at least a step in the right direction.

In seeking an understanding of what happened, battlefield historians never fail to focus on Custer’s perceived mistakes, rather than the Indians’ brilliant and strategic use of the topography of land they knew intimately.

Although Hollywood westerns invariably portray Custer’s gallant little band fighting to the death as mounted Indians conveniently gallop around them in full view of the Seventh’s guns, the reality was very different.

The Indians artfully used ravines and gullies to crawl closer to the dismounted cavalrymen as fighting escalated. Until the final stages Custer’s troopers probably only snatched fleeting glimpses of the enemy they were up against.

The struggles of the Native Americans go on. My visit coincided with the birth of the Dakota Access Pipeline protests when members of the Standing Rock Sioux tribe took direct action over what they considered a serious threat to the region’s water.

Barack Obama ordered a halt for judicial reasons, only for his White House successor, Donald Trump, to allow work to re-commence. As of now, the 1,170-mile pipeline continues to operate…

I continue my grim walk towards the Little Bighorn, pausing only to examine white marble markers where men died. Like generations of sombre visitors who have tramped this path before me, I am lost in my own bleak thoughts.

And always at the back of my mind is the stark realisation I am nearing the probable site where Sgt William Batine James – the sole Welshman to fight here – met his gruesome demise…

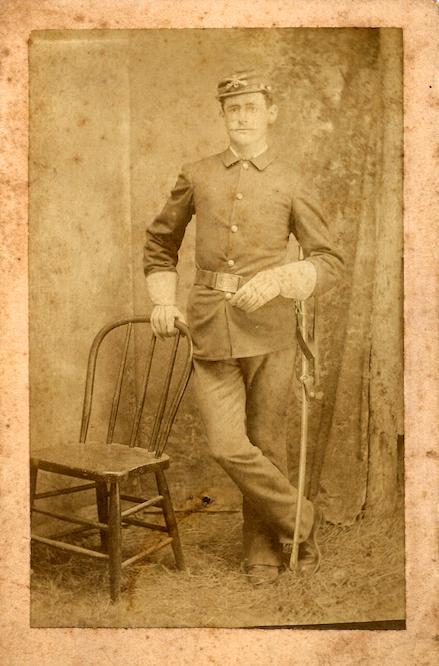

My debut novel, ‘If God Will Spare My Life…’, published by Victorina Press, is a re-imagining of what prompted him to emigrate to the United States and enlist in the Seventh.

Its framework is built around my discovery of five letters this lost Victorian soldier sent home to his youngest brother, John Clement James, before vanishing in the mists of time.

Yet a photo of Will James remains frustratingly elusive – I know he dispatched one home as he says so in those letters…

Jolted from my deliberations I pause at a sign reading ‘Trail End’. It is both literal and metaphoric as I am standing at the lip of Deep Ravine, the most remote and sinister part of the battlefield, where 28 bodies of members of E Troop – James’s company – were found.

Was he among the last of Custer’s desperate bluecoats to fall? My continuing research suggests he may have been the lone trooper who reached the river. Unable to shift my sombre mood, I cast some soil I have bought from his birthplace – Pencnwc Farm in Dinas Cross – into the yawning gulch.

Sadly, the James family went to their graves unaware of his fate.

Papers reveal executors of John Clement James’s estate were still searching for evidence his elder brother was alive over thirty years later as Will stood to inherit the family farm on Strumble Head, near Fishguard.

But then, ‘Will o’ the Wisp’ is always tantalisingly just out of reach…

‘If God Will Spare My Life…’ published by Victorina Press, can be purchased here or on Amazon.

The novel has been adapted into a play – ‘Ghost Rider’ – to be premiered at Fishguard’s On Land’s Edge Festival in September.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Interesting article and the book is a great read. Thoroughly researched, capturing the atmosphere of both West Wales and the developing USA really well.

9/11 strange choice Kemosabe

I work off season at the Little Bighorn Battlefield and spent a decade working to make the Indian Memorial a reality. I need to correct you on one important fact. The memorial marker at the mass grave of the horse bones sits along the asphalt trail to the Indian Memorial. The horse memorial and the Indian Memorial were both dedicated in 2003. The horse memorial was not placed decades before the Indian Memorial as stated in this article. Note: The sketch of the horse on the horse memorial marker as well as the marker itself was designed by retired Chief… Read more »