Hitler, Stalin, and Mr Jones – the story of a true Welsh hero

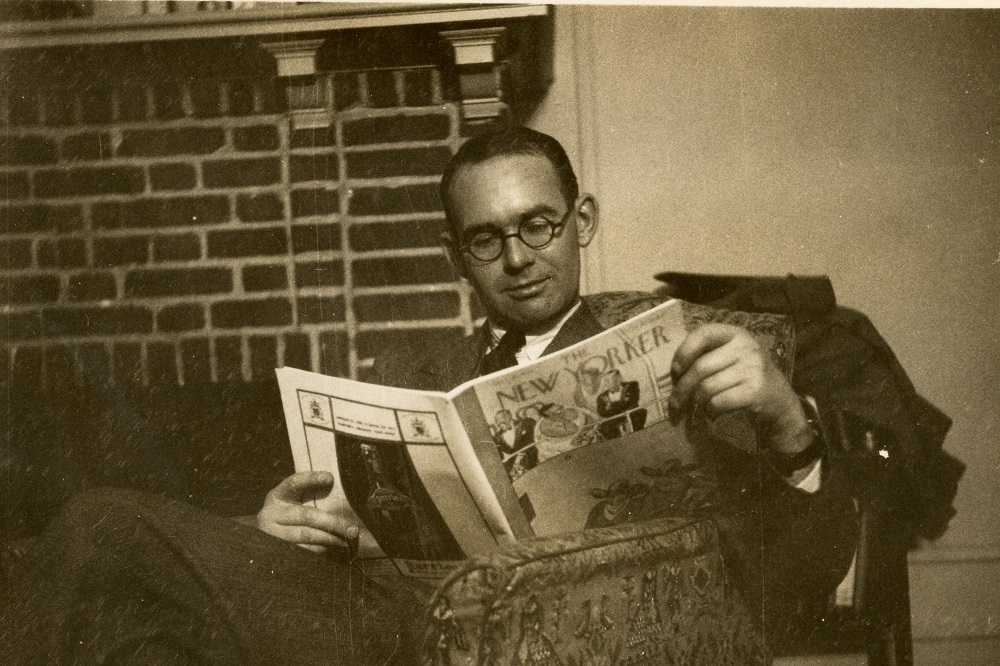

The heroic Welsh journalist Gareth Jones was born on this day in 1905. To mark his birthday we revisit this article published earlier this year.

Christopher Evans

There are many unsung heroes throughout Welsh history. People who have fought for human rights, struggled against oppression and repression, challenged those in power, and championed the underdog. Importantly, there are also those who exposed corruption and told the truth. The erudite and courageous investigative Welsh journalist Gareth Jones, who was tragically murdered so young for telling the truth, certainly falls into the hero category.

Today in Milan, a plaque was unveiled by the Gardens of the Righteous Worldwide (Gariwo) to honour Jones as a defender of human rights and for his role in uncovering the horrors of the Great Soviet famine of 1933.

In particular, Jones is known for exposing Holodomor – the appalling man-made famine in the Ukraine. The terrifying and tragic consequences of Stalin’s rapid collectivisation policy were witnessed first-hand by Jones, who was determined to make the world aware of the millions of people dying across the Soviet Union.

Philip Colley, the great-nephew of Gareth Jones, gave a speech at the event in Milan, describing him as “a true internationalist” who growing up in the shadow of the First World War “understood full well the danger and disaster that can be brought to ordinary people by those who misuse national identity for political or violent ends.”

Barry

Gareth Jones was born in Barry on 13th August 1905. His mother, a tutor, worked for the nephews of John Hughes, the famous Welsh industrialist responsible for founding Hughesovka, now Donetsk in the Ukraine. Intrigued by the stories from overseas, Jones discovered a love for learning and was fascinated by different international cultures and languages. The studious Jones excelled at school and went on to study French at Aberystwyth University, where he achieved a first-class honours degree in 1926.

Three years later, he attended Trinity College at Cambridge University, once again excelling with a first in French, Russian, and German. A polyglot, Jones was fluent in five languages – Welsh, English, French, German and Russian. He loved travel, his curiosity taking him to Russia and Germany, where his linguistic skills helped him to integrate and discover the cultural, political and social elements of the countries. It opened his eyes to the wider world.

David Lloyd George

Following his travels, in 1930 he began working as a foreign affairs advisor for David Lloyd George, the Welshman who had been Prime Minister from 1916 to 1922. It was during this role that the young Jones’ inquiring mind led him towards a journalistic path. Indeed, Lloyd George himself observed that his employee had an “almost unfailing knack of getting at things that mattered.” Jones certainly had an instinct for being in the right place at the right time.

This was proven in 1933, when through contacts, Jones found himself on a flight aboard Hitler’s private plane. In doing so, he became the first foreign observer to fly with Germany’s new chancellor and future self-proclaimed führer. He had also been in Leipzig when Hitler was made chancellor.

Many of his contemporaries criticised Jones for his links with the Nazis, accusing him of being a sympathiser. It couldn’t have been further from the truth. Jones was determined to find reason for and expose the rise of fascism, something that had been accelerating in Europe, partly due to the Great Depression of the 1930s. He could also see the anti-Semitism that lay at the core of Nazism and foresaw what was to come.

Sitting just feet away from Hitler and Jones was the nefarious Joseph Goebbels, who had been impressed by the “intelligent young man” accompanying them. The feeling was not mutual, with Jones writing “if this aeroplane should crash, then the whole history of Europe would be changed” and that “a few feet away sits Adolf Hitler, Chancellor of Germany and leader of the most volcanic nationalist awakening which the world has seen. The occupants of the plane are, indeed, a mass of human dynamite.” This proved to be catastrophically prophetic.

Genocide

Jones’ biggest scoop, one that perhaps eventually cost him his life, would come during his third visit to the Soviet Union in 1933. Whilst in Moscow, the intrepid Jones tried to make his way to Kharkiv, the then capital of Ukraine. This was despite Stalin forbidding foreign journalists to leave Moscow. During his surreptitious sojourn, Jones travelled by train and then on foot. Walking through remote villages, Jones witnessed suffering and starvation on inconceivable scale that horrified and appalled him. It was a barbarity that the world was completely unaware of.

Not long after crossing the border into Ukraine, he was discovered by the Soviet police, who escorted the young journalist to Kharkiv. Here he witnessed further suffering and atrocities. His proficiency in languages meant that he could converse with the peasants and peasant farmers he met, who told him of the dying and the starvation. Children, mothers, fathers.

Many cried out for bread – for anything. This famine in the Ukraine was known as Holodomor, or the Terror-Famine, and was responsible for millions of Ukrainian deaths. The cruelty and starvation was not just limited to Ukrainians. Jones saw Kazakhs, Cossacks, Russians, and German colonists in dire circumstances too.

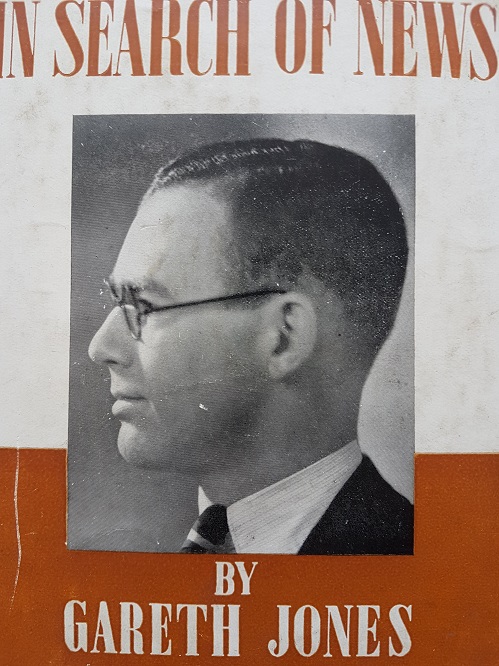

His reporting of his clandestine findings set Jones out on his own. A rigorous note-taker, fact finder and truth teller, his diaries and accounts of what he encountered were pioneering and are now seen as the one true source of evidence of the famine. He had first called a press conference in Berlin to share his story, before his reports were published by the Manchester Guardian and the New York Evening Post revealing the horrors of Holodomor.

Speaking at the event in Milan, Jones’ great-nephew Philip Colley said: “They were all, as precious individuals, victims of Stalin’s disastrous policies, not least collectivization. They all deserve to be remembered and given a voice. And, thanks partly to Gareth as a brilliant journalist and a true humanitarian, Stalin’s crime against humanity was revealed to the world as it was taking place. He gave them that voice. But, at the time, the world did not want to hear.”

Despite his bravery and journalistic rigour, many poured scorn on Jones’ reports, labelling him a falsifier and fantasist. He was ostracised by the mainstream media and found himself struggling to find work, eventually returning home to live with his parents. His next job was as a reporter with the Western Mail.

In his speech in Italy, Colley said that his great uncle stuck to his guns in his quest for the harrowing truth to be told. Jones’ proclamations angered the Soviet authorities, who had denied all knowledge of such atrocities.

“Gareth couldn’t turn a blind eye. His righteousness compelled him to speak out and speak the truth. And for doing that, for daring to be a Daniel, and standing against the prevailing narrative, he paid a terrible price. As those who speak the truth often still do today. He was accused of being a liar by the other Western journalists in Moscow. Back home in Britain he was shunned by many of his former friends in high places, including his former boss David Lloyd George. In many ways he lost his reputation. And two years later, in the service of journalism, he lost his life.”

Wanderlust

Life in a Welsh newsroom proved to be too soporific for Jones and wanderlust soon set in. His itchy feet led him on a round-the-world journey, taking in North America, Hawaii, China, Japan and Mongolia. It was whilst on this trip that Jones first heard of the brutal Japanese occupation of Manchuria (Manchukuo), then located in Inner Mongolia. In his quest for truth, Jones would pay the ultimate price. Along with a German journalist, it is thought that he was kidnapped by Mongol bandits in the remote countryside. His companion, somewhat curiously, was soon released. Jones was not so lucky. On 12th August 1935, he was executed just a day before his 30th birthday.

His untimely death is still shrouded in mystery today. Theories have varied from the Japanese instructing the kidnappers to murder Jones, whilst many believe that the NKVD – the Soviet Secret Police – were responsible for his execution in an act of revenge for his exposé of the Soviet famine.

Diaries

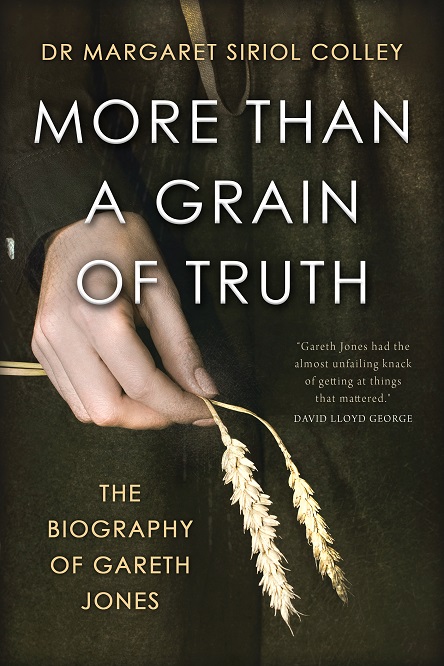

Jones’ incredible achievement in unmasking the horrors of Holodomor were largely confined to history. That was until 1999, when his diaries, notes and letters were discovered by his niece Dr. Margaret Siriol Colley following the death of Jones’ sister Gwyneth. Her tireless and diligent research into her uncle’s short but fascinating life produced two books, The Manchukuo Incident (2001) and More Than a Grain of Truth: The Biography of Gareth Richard Vaughan Jones (2005). He has also been the subject of the BBC Storyville ‘Hitler, Stalin, and Mr Jones’, and the 2019 film Mr Jones. In 2022, renowned Welsh journalist Martin Shipton also published a biography titled Mr Jones – The Man Who Knew Too Much: The Life and Death of Gareth Jones.

Since the passing of his mother, Philip Colley has continued to keep his great uncle’s memory alive. Like his revered relative, Colley is a traveller and linguist, who used to take people on tours of the Far East. Now running a campsite near Hastings in East Sussex, Colley says his uncle’s work is more important now than ever.

“It would seem there are parallels (with today’s world). As in Gareth’s day, the world seems to be dividing into different camps and the advent of war makes truth increasingly hard to find in either.”

Colley hopes that journalists and aspiring journalists will be inspired by his uncle, and most importantly, be inspired to tell the truth.

“They (good journalists) certainly exist but are in my opinion increasingly hard to find in the mainstream media. One is more likely to come across them in the webpages of outlets like Reporters Without Borders, Democracy Now, Forbidden Stories and the Electronic Intifada, places where the journalists are permitted to follow the stories that challenge and disrupt mainstream narratives, rather than staying within the parameters set out by publishers who are heavily invested in the status quo; where journalists give voice to the voiceless and the oppressed, rather than to the powerful and the oppressor.

As with my great uncle, there are still perils in telling the truth; there are indeed many such as Shireen Abu Akleh and Julian Assange who have in their different ways found. There are still good journalists out there carrying on in the spirit of Gareth Jones, but we need many more of them, and now more than ever. And it is important that we protect and defend them when their stories bring them into conflict with powerful elites.”

Forgotten

When his life was cruelly cut short, Gareth Jones was predominately a forgotten journalist, his work either ignored or disregarded.

Through the work of his resolute family, his story has been kept alive and he is now rightfully lauded as one of the greatest journalists Wales has ever produced.

He was fearless in his pursuit of facts and truth. With the Russian invasion of Ukraine, his journalistic endeavour to uncover unimageable savagery resonates now as much as ever. In these post-truth times, how the world could do with a Gareth Jones.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Surely Gareth Jones should be honoured here with a statue outside the School of Journalism in Cardiff. Such a great man

Absolutely in agreement; he’s one of the “enwogion” we sing about in our national anthem. Every paper should print this article.

Yet still the vile Walter Duranty of the New York Times keeps his burnished record as a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist for his glowing reports sycophantically praising Stalin! He denied totally any policy of starvation in Ukraine and heaped libel and contempt upon Jones. Of course, most intellectuals in the West believed the Communist fellow-traveller Duranty. The honesty of Gareth Jones and the similarly open-minded George Orwell was not appreciated by the Romantic ideologues of the Left. We live today at a time that desperately needs some of their sane objectivity.