House of Dogs: the last squires of Trecwn

We begin a new series about Trecwn in Pembrokeshire which traces colourful family histories and tells the story of a quiet valley’s transformation into a naval weapons depot.

Howell Harris

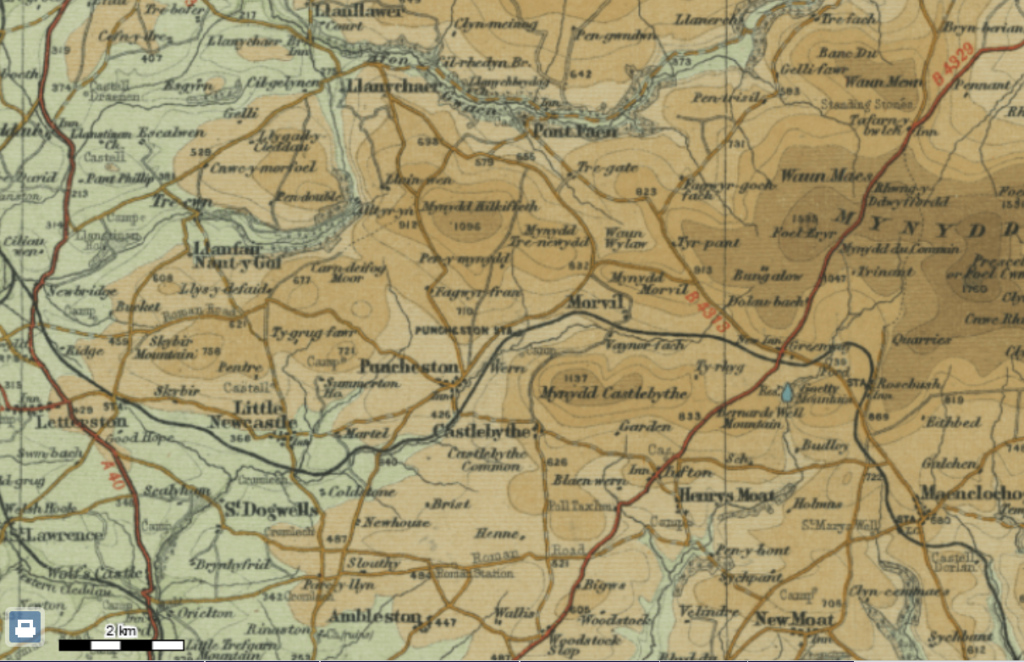

This is the story of the last squires of Trecwn, an ancient estate that at the end of the nineteenth century still covered about 4,500 acres, stretching seven miles from West to East. Its heart was the mansion of Tre-Cwn (the House of Dogs) and the hamlet of the same name (but without the hyphen) in a beautiful, unspoilt valley on the southern edge of the Preseli Hills in north Pembrokeshire. As one of the estate’s tenant farmers, John Lloyd of Penffrwyd, wrote in 1906,

Mae dyffryn Trecwn yn un prydferth,

Mae ynddo amrywiaeth i’w gael,

0 bob math o goed ac o ffrwythau,

Sy’n dweyd fod y Crewr yn hael;

The name of the valley is Nant-y-Bugail (the valley of the shepherd). The Afon Cyllell runs west to join the Western Cleddau, while the Afon Aer flows north from the watershed to meet the Gwaun. Up until ninety years ago it was renowned for its beauty and peaceful seclusion.

To the local naturalist Ronald Lockley, who made winter pilgrimages there to watch the murmurations of the huge flocks of starlings roosting in its ancient woods, it was “that wonderful glen,” “this most enchanting place,” an “evergreen … sanctuary.” “It is as if one of the finest slices of the Gwaun Valley had been lifted up and dropped down into a yawning crevice a few miles to the west—a valley like the Doon in Blackmore’s immortal story, as guarded by crags, but more verdant with trees and rhododendrons.”

Lockley was not the first person to admire it, though he would be among the last to see it in this pristine state. John Wesley, who knew the British Isles better than most of his contemporaries, enjoyed the hospitality of the Vaughans, the local landowners, on five visits to their mansion in the 1770s and 1780s.

Wesley thought Trecwn “one of the most delightful spots that can be imagined,” even “one of the loveliest places in Great Britain,” “that lovely retirement, buried from all the world in the depth of woods and mountains,” “having no resemblance to any place I have seen.” He preached to local followers under one of its great oaks, a spot still marked with a monument but now inaccessible.

A generation later Richard Fenton, writing his topographical tour of Pembrokeshire, concurred. “Trecoon,” as he called it, spelling phonetically, “in point of situation, yields to very few spots in the county, as possessing every ingredient of fine scenery, being situated on the edge of a steep hill, having a higher at its back, sheltering it from the north above the narrow vale which the little river … rises in, and runs through, having the boundaries on each side nobly wooded.”

Fenton’s priorities were not Wesley’s, nor for that matter Lockley’s: the estate provided “ample room and subject for amusement to the sportsman,” with the Cyllell’s “native trout … being large, red, and of high flavour.” The landscape needed almost no “improvement,” and Trecwn offered “the most desirable residence that a moderate fortune, directed by judgment and taste,” could supply.

By Fenton’s time the Vaughans had died without issue, so the estate passed through a married sister to her husband, Joseph Foster Barham, MP for Stockbridge in Hampshire and owner of large estates in Westmoreland and Jamaica, and the slaves to work the latter too. Trecwn would remain in his family for the next hundred and thirty years, passing briefly to his son John, who went mad and died young, and then to his younger son Charles, who came into possession in 1840 and made it his main home from the early 1850s until his death in 1878.

Charles was an Anglican minister by vocation if not occupation, and he and his wife became renowned in the area for their generosity, and particularly her support for popular education. After her death he and her brother, more sympathetic to Methodism, sponsored the building and running of a large, impressive school as her memorial. It served neighbouring rural parishes until the early 2000s and was said to have cost £7,000 to build (c. £3.5 million at current values), with a £5,000 (£2.5 million) endowment to operate and maintain it.

It was owned by the Wesleyan Conference Education Trustees and operated via a curious blend of annual oversight of its religious teaching by the Secretary of the Methodist Education Committee, and local management by a committee representing the neighbouring Anglican parishes and their ministers, plus the current owner of Trecwn, “not being a Roman Catholic.” The Methodist connection was designed to guarantee that its religious instruction remained strictly Protestant and evangelical, with no risk of becoming High.

Charles also developed Trecwn as a sporting estate, locally celebrated for its fox and otter hunting, hare coursing, and shooting, particularly of woodcock as well as the inevitable pheasants. The valley bottom became dense with rhododendrons, laurels, and alders, providing wonderful covers.

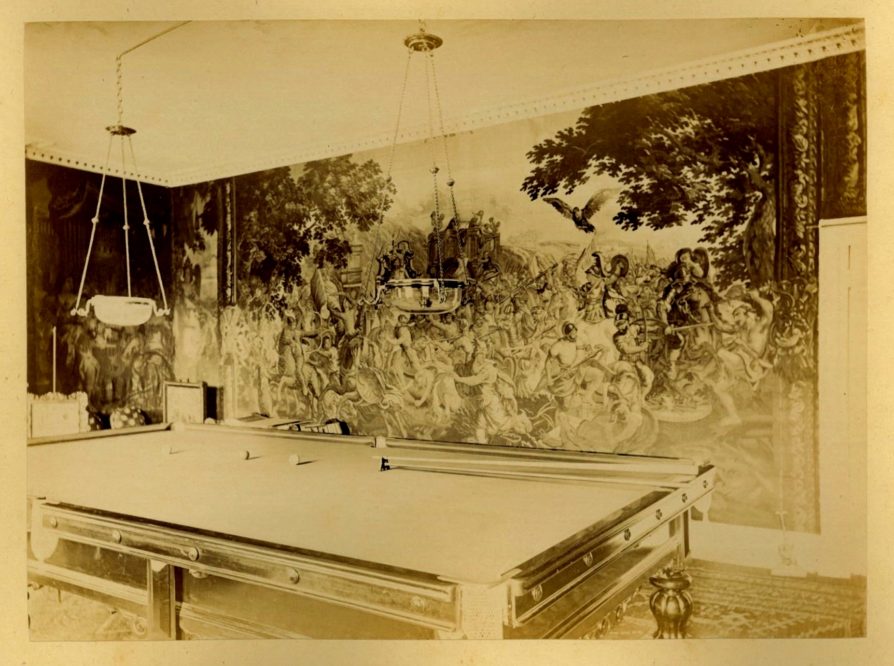

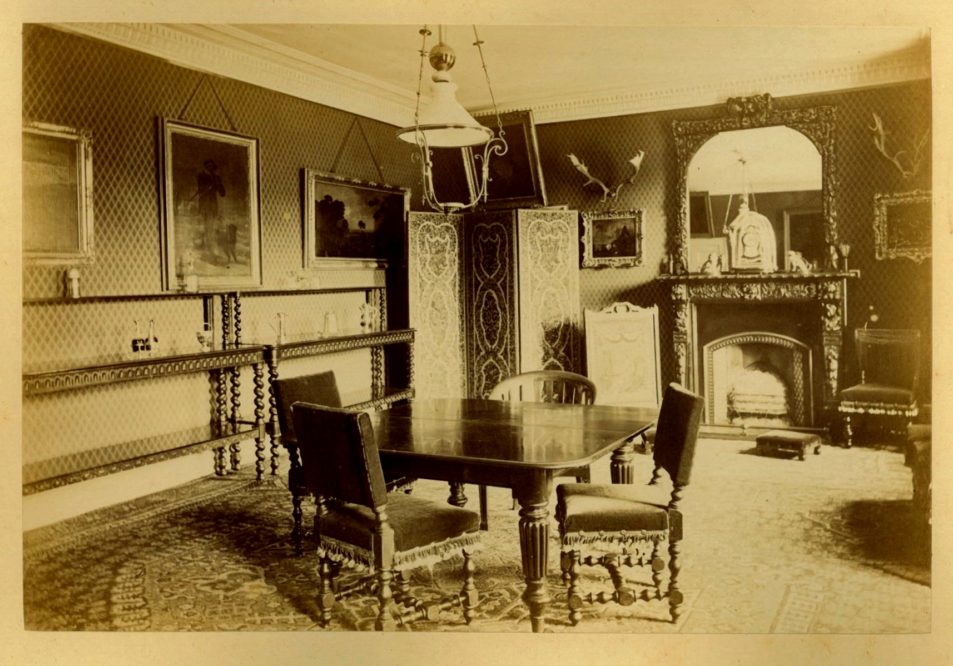

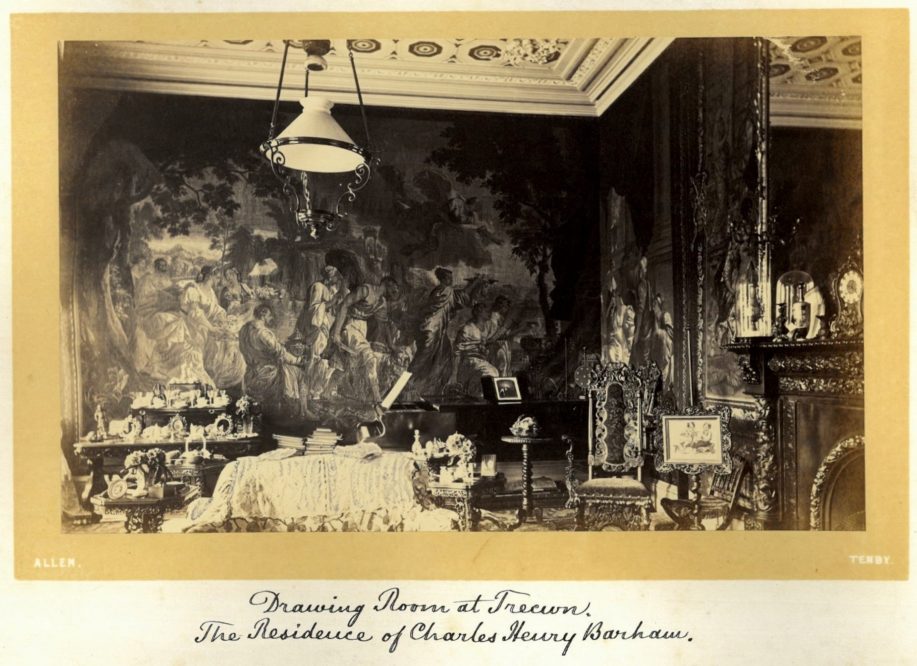

The house was large if not particularly attractive, with the usual accoutrements — walled gardens, aviaries, stables. It was also richly furnished: on Charles’s death there was a sale at Christie’s of carved furniture and over twenty tapestries (Beauvais, Brussels, etc.), the grandest 30 feet by 12. This gives us a sense of the size and style of the rooms they decorated, as do surviving photographs of a few rooms in their 1871 Victorian splendour. Sotheby’s auctioned off his extensive library separately — “books of prints, Greek and Latin classics and translations, works on the fine arts, poetry and the drama, antiquarian publications, scrap books containing engravings and original drawings, miscellaneous books on the different branches of English and foreign literature.”

For the next twenty years the estate was owned by Charles’s sister Caroline (b. 1810), the widow of another Anglican minister (and vehemently anti-Catholic theologian and controversialist), the Rev. Sanderson Robins. She maintained the family custom of generosity to the tenantry and local good causes but was not permanently resident. Caroline rented out the shooting and, for most of the 1890s, the house too, to another local gentry family.

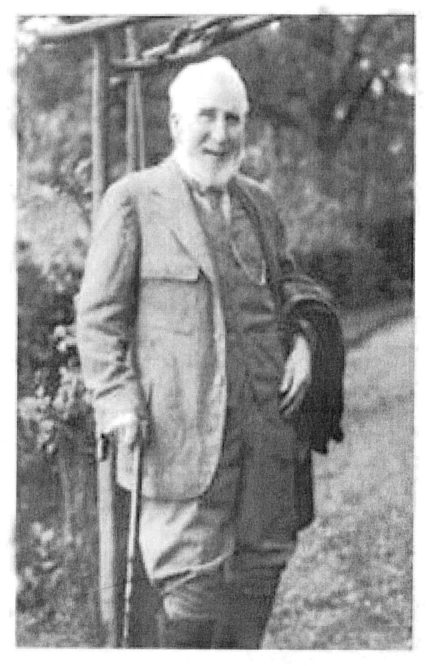

On her death in 1899 Trecwn passed to her son Francis (b. 1841), who took the name Barham and moved in when the tenants left. He and his son Cyril (b. 1873), who succeeded him in 1928, would be the final family members to own and occupy it. Their troubled lives and deaths, and the sad history of the valley after Cyril’s heirs sold it in 1936, will be the focus of the rest of this series.

Francis’ story is of a promising military career ended by sunstroke, madness, and insubordination shortly after he turned 30; of a false accusation leading to strip-searching by the Paris police, and a well-publicised diplomatic incident; of chronic drunkenness and a violent, unhappy marriage in his 30s and 40s; of serial infidelity and two very newsworthy divorce cases in his 40s and 50s; of mistresses, more court cases, and endless quarrels with Trecwn neighbours in his 60s and 70s; of assault at the hands of the radical atheist local schoolmaster, and the resulting vendetta between them ending in the latter’s dismissal; and finally of quiet contentment in his 80s, near death by drowning, then death at Trecwn, in the arms of his beloved, in 1926, terminating a life almost empty of achievement though not, fortunately, of incident.

Cyril’s life was shorter but no more fulfilled: an unhappy, unsettled childhood; a wretched relationship with his father; educational failure; a mediocre career as a solicitors’ clerk and minor civil servant during a life in suburban London only made interesting by his unconventional marital arrangements; a bitter, costly, and only partly successful struggle to overthrow his late father’s will, which had disinherited him; another bitter but less expensive attempt to prosecute his father’s executors, for having carried out his wish to be cremated; a falling-out with his gentry neighbours when he stopped the Hunt coming onto his estate; an enormously costly prosecution for slander, after he had accused a local doctor of sexual and other misconduct; and finally, death in a motor accident that also killed his wife and son in 1933.

Trecwn was left to his young daughters, but they had little fondness for it, did not stay there, and were quite content to be relieved of it by the Admiralty in 1936. A thousand acres — the whole of the valley, and the heart of the estate — were purchased and transformed over the next few years, at vast expense, into an enormous naval weapons depot that at its wartime peak employed a couple of thousand people. The depot remained in business until the early 1990s, still providing hundreds of the best jobs in Pembrokeshire right up to the end.

Its closure left a huge gap in the local economy that has never been filled, and can never be, despite the Welsh Government’s rather desperate attempt to do so by declaring it to be an “Enterprise Zone”. Small and unsuccessful attempts to make something of it by subsequent private owners mean that today, almost 90 years after the valley’s fate was sealed, it remains as a largely vacant, increasingly derelict, but still quite beautiful anomaly. It is a fenced enclosure right on the edge of the National Park, closed to the public, but still, fortunately, open to the wildlife that drew Ronald Lockley to it before it lost its innocence forever.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.