How a Welsh soldier’s beautiful singing caused a truce on the battlefield

David Owens

A newspaper article revealing the extraordinary story of the Welsh soldier who brought a halt to fighting in the bloody fields of Flanders during the First World War has been unearthed.

Many will know the famous story of the Christmas Day truce on the Western Front in December 14, when troops emerged from the trenches sang carols, exchanged gifts of food and tobacco and most memorably played football together.

In most cases these ceasefires lasted for two to three days before the brutality of war returned to shatter the peace of Christmas.

However, a story lost to the annals of time, no less remarkable or poignant has been unearthed and can finally be told.

It was discovered in the archives of the National Library of Wales’ Welsh newspaper collection by the Museum of Wales Hip hop Coordinator Kaptin Co-ordinator Kaptin Barrett, who was carrying out research when he happened upon this wonderful story.

He contacted Nation Cymru and said: ‘I was recently going through the Welsh newspaper archives (trying to find the earliest mentions of jazz) and came across this great story about a brief cease fire in World War 1 caused by a Welsh soldier’s singing. Thought you guys might be interested.’

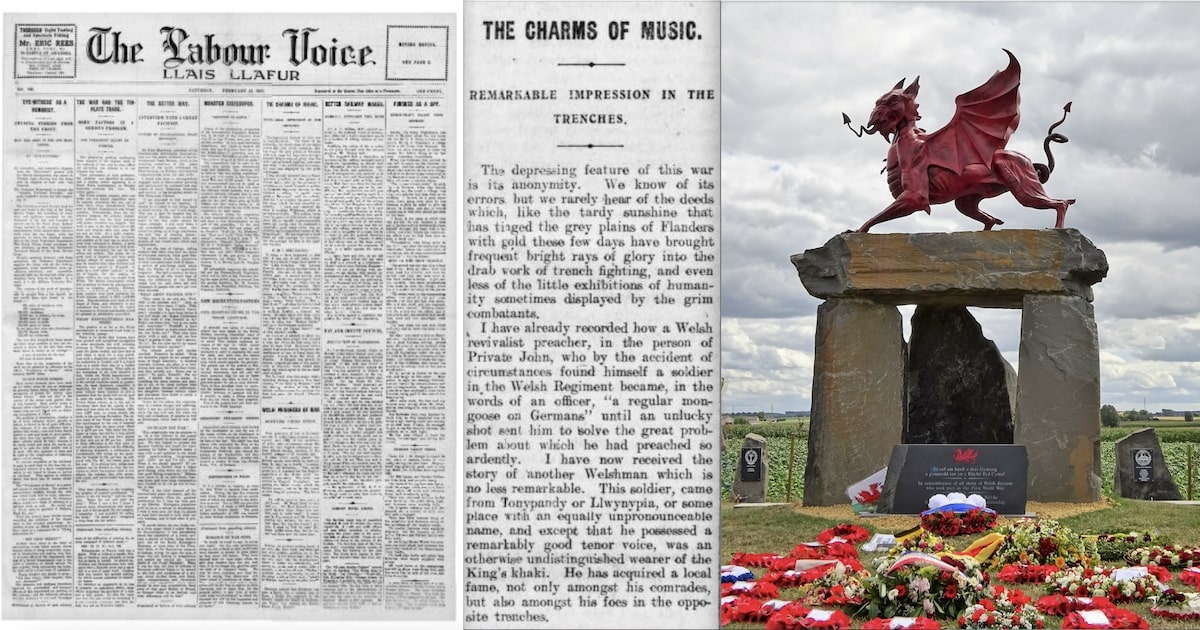

Two months after the the Christmas truce, in February 1915, the article was published in weekly bilingual newspaper Labour Voice (Llais Lafur).

It’s a story that appears to be written by a correspondent relaying stories back to the newspaper of the hardships of life for Welsh soldiers in the unforgiving battlefields of Flanders in Belgium.

It tells of the remarkable gift of one Welshman whose beautiful singing brought about a ceasefire, both British and German troops laying down their guns to listen to the wonderful sound of this talented soldier’s singing.

Headlined: THE CHARMS OF MUSIC. REMARKABLE IMPRESSION IN THE TRENCHES – here is the story in full…

The depressing feature of this war is its anonymity. We know of its errors, but we rarely hear of the deeds which, like the tardy sunshine that has tinged the grey plains of Flanders with gold these few days have brought frequent bright rays of glory into the drab work of trench fighting, and even less of the little exhibitions of humanity sometimes displayed by the grim combatants.

I have already recorded how a Welsh revivalist preacher, in the person of Private John, who by the accident of circumstances found himself a soldier in the Welsh Regiment became, in the words of an officer, “a regular mongoose on Germans” until an unlueky shot sent him to solve, the great prob-lem about which he had preached so ardently.

I have now received the story of another Welshman which is no less remarkable. This soldier, came from Tonypandy or Llwynypia, except that he possessed a remarkably good tenor voice, was an otherwise undistinguished wearer of the King’s khaki.

He has acquired a local fame, not only amongst his comrades, but also amongst his foes in the opposite trenches.

“HOB Y DERI DANDO.”

It seems to have happened in this way. It was one of the many miserable nights which troops have spent in the muddy trenches. Our outlook from our trench across the flat fields of Flanders was one of the most forbidding kind. It rained heavily, and always the mud was semi-liquid, knee deep, and frigidly cold.

There was no sound beyond the occasional “plip plop” of a German rifle, and the sharp bark of a reply. In these circumstances, the gallant Welshman suddenly lifted up his heart in song. He sang a merry WeIsh ballad, ‘Hob y Deri Dando’, and when he had finished from the opposite trench there came, in excellent English, a demand for more.

So once again the clear voice was lifted up into the grey night. This time the song was ‘Mentra Gwen’, and again the Germans applauded. ‘Have you got Caruso there?” one of them shouted across.

At this time it seemed to dawn on both sides that singer had created a truce, for whilst he had sung not a shot had been fired. Everyone within earshot had momentarily forgotten the deadly work of war to hang upon the melodies arising from the mud of Flanders.

A bargain was struck on German proposition that if the soldier with the beautiful voice would sing again they would agree to fire no more until daylight. For the third time the singer entertained his strange audience, this time choosing ‘Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau’, and the stirring strains of the Welsh national anthem arose for perhaps the first time over the dismal Flemish morass.

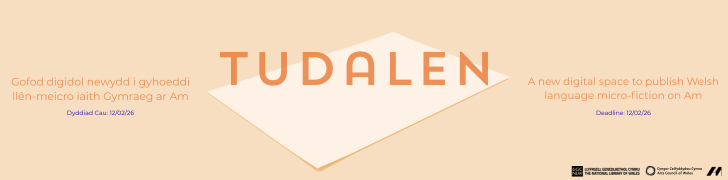

This momentary respite from the horror of a war that saw so many Welsh troops lose their lives along the Western Front in such bloody battles as Passchednale and Mametz Wood was a rare glimpse of humanity as terror reigned down on both sides.

According to records he First World War (1914–1918) saw a total of 272,924 Welshmen under arms, representing 21.5 per cent of the male population. Of these, roughly 35,000 were killed, with particularly heavy losses of Welsh forces at Mametz Wood on the Somme and the Battle of Passchendaele.

The 1st and 2nd battalions of the Royal Welch Fusiliers served on the Western Front from 1914 to 1918 and took part in some of the hardest fighting of the war, including Mametz Wood in 1916 and Passchendaele in 1917.

The Welsh-language poet, Hedd Wyn was part of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers and was killed during the first day of the Battle of Passchendaele during World War I. He was posthumously awarded the bard’s chair at the 1917 National Eisteddfod for a poem he wrote on his way to the frontline.

His poem Rhyfel (War) exposes the futiliy and horror of the First World War

Gwae fi fy myw mewn oes mor ddreng,

A Duw ar drai ar orwel pell;

O’i ôl mae dyn, yn deyrn a gwreng,

Yn codi ei awdurdod hell.

Pan deimlodd fyned ymaith Dduw

Cyfododd gledd i ladd ei frawd;

Mae sŵn yr ymladd ar ein clyw,

A’i gysgod ar fythynnod tlawd.

Mae’r hen delynau genid gynt,

Ynghrog ar gangau’r helyg draw,

A gwaedd y bechgyn lond y gwynt,

A’u gwaed yn gymysg efo’r glaw

Why must I live in this grim age,

When, to a far horizon, God

Has ebbed away, and man, with rage,

Now wields the sceptre and the rod?

Man raised his sword, once God had gone,

To slay his brother, and the roar

Of battlefields now casts upon

Our homes the shadow of the war.

The harps to which we sang are hung,

On willow boughs, and their refrain

Drowned by the anguish of the young

Whose blood is mingled with the rain.

WE WOULD LOVE TO FIND OUT MORE ABOUT THIS STORY AND THIS REMARKABLE MAN WHOSE SINGING VOICE BROUGHT TEMPORARY RESPITE FROM THE HORROR OF WAR.

IF YOU HAVE ANY INFORMATION THAT COULD HELP US PLEASE EMAIL [email protected]

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Brilliant story. This is something to be told.

‘……. This soldier, came from Tonypandy or Llwynypia, or some place with an equally unpronounceable name.’ Typical! This cheap and insulting quip passed for humour back then, and, alas, still does in some quarters.

You have me a little puzzled, I cannot find the second half of your quote in the text. A remarkable story though, very moving…

My mother’s father ( in action for the entire war) finally died of his injuries after years of suffering two years before I was born…

I’ve sat in that chair of Hedd Wyn’s and I am going to look into this a little bit more.

Thanks to all concerned for bringing it to my notice. They are doing great things in Aber on the archive I hear…

Pity about that extra bit of text though…

His uniform was that of an infantry soldier of the 2nd Battalion, The Welsh Regiment, so dressed in khaki, he was therefore indistinguishable from his ‘pals’ and nothing to do with ‘place names’. Only his beautiful voice set him apart. The 2nd Battalion won the regiment’s first Victoria Cross by the way… Maybe you could apologise to all those people who worked hard to put that knowledge in front of you, and the memory of all those men living and dying in the mud of Flanders, supposedly resting after the First Battle of Ypres during the ‘Winter Operations’ of 1914-15…… Read more »

An inspiring article. especially to see the translation of the work of Hedd Wyn