How opposing Charles’ investiture restored the national movement’s self-respect

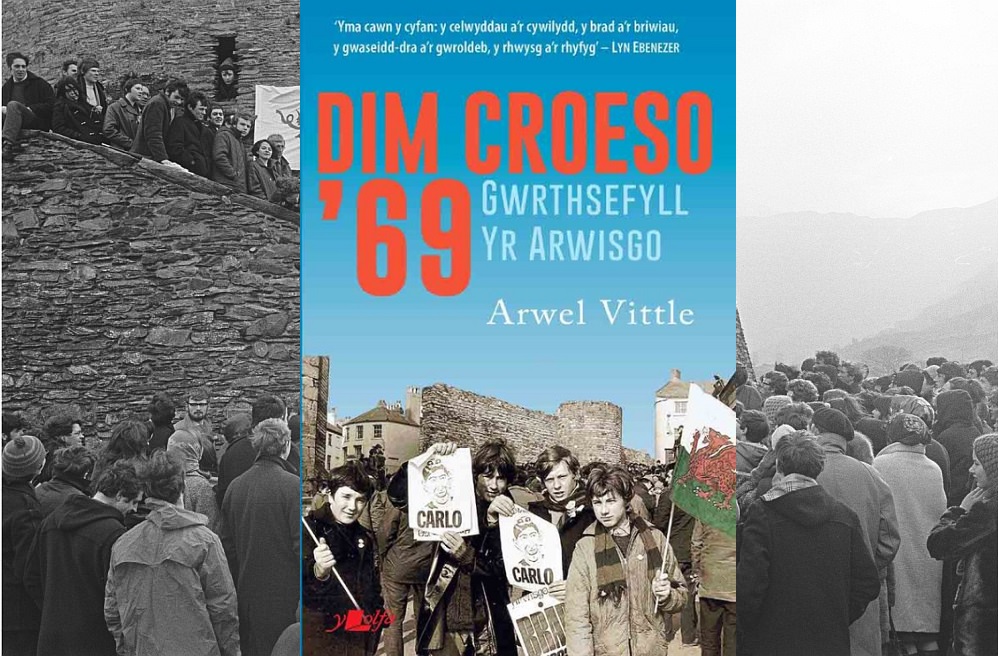

On 1st July this year it will be 50 years since the investiture of Charles, Prince of Wales. Here Arwel Vittle, author of the new book Dim Croeso ’69 looks back at the significance of the period…

Two key events and their political impact stand out in the history of 1960s Wales. The first is the decision at the onset of the decade to drown Cwm Tryweryn, and the second is the Investiture of Charles as Prince of Wales in 1969 at the decade’s close.

On the one hand, the failure to prevent the loss of Capel Celyn was a testament to the political weakness of the national movement in Wales, while on the other the fierce opposition to the Investiture was a sign that perhaps the national movement was not as moribund as many nationalists feared.

The aim of my book Dim Croeso ’69, recently published by Y Lolfa to mark the 50th anniversary of the Investiture, is to give readers an idea of what it was like to be at the heart of the protests; combining oral history with a narrative of the events leading up to the ceremony in Caernarfon.

Turmoil

The nation’s communities and institutions were riven by the Investiture. Plaid Cymru, and Gwynfor Evans in particular, was caught on the horns of a political dilemma of whether or not to oppose the event. The Urdd was split from top to bottom, with serious divisions also apparent in the Gorsedd and non-conformist denominations.

Students across all University of Wales campuses held several sit-in demonstrations and hunger strikes to mark their opposition to the Investiture. On top of all of this, and adding significantly to the ferment and tension, the FWA’s dramatic quasi-paramilitary appearances and Mudiad Amddiffyn Cymru’s bombers.

So much was the turmoil in the years and months leading up to the ceremony in July 1969, that the authorities had to draft scores of soldiers, detectives and even agents provocateurs, to ensure that the ceremony could pass without incident in Caernarfon.

Satire

A major element of the Investiture protests was a generational conflict between young and old, and in many respects, 1969 was Wales’ 1968 – with a generation of young people rebelling against what was seen as the older generation’s staid and sentimental Welshness.

Satire is traditionally a weapon of the weak against the strong, and the Investiture proved to be an excellent target for satirists – from the mocking cartoons of Tafod y Ddraig and Lol to Dafydd Iwan’s records.

What better target for ridicule for young nationalists who wanted to change and modernise their country, than a pseudo-medieval ceremony in a castle full of obsequious old men?

Insurgent

However, the resistance was not uniform. It ranged from Cymdeithas yr Iaith’s non-violent mass protests, to the theatrics of the FWA and the Patriotic Front, and MAC’s sustained bombing campaign.

One of the main motives of John Jenkins, MAC’s ‘organiser in chief’’, was to remind the Welsh themselves, as well as the British state, of their existence as a people and as a nation: ‘We’ve never existed. We were never here. We have only been shadows from God knows where.’

However, direct action was not without cost, and two members of MAC, Alwyn Jones and George Taylor, were killed on the eve of the Investiture when their bomb exploded prematurely at Abergele.

Although many members of these groups did not agree with each other’s methods, then or now, they all in their different ways contributed to creating an insurgent atmosphere.

These acts of resistance, along with Plaid Cymru’s by-election gain in Carmarthen, and near misses in Rhondda West and Caerphilly, reinforced the feeling that something significant was happening.

Nationalists generally view the Investiture as a plan by the Labour Government to stem Plaid Cymru’s surge in the late sixties. Whatever the truth of that, Labour politicians such as Prime Minister Harold Wilson and the sycophantic royalist and Secretary of State for Wales, George Thomas, undoubtedly took advantage of the occasion to undermine Welsh nationalism at every turn.

Protestors

The public face of the protesters was Dafydd Iwan, not only as Chair of Cymdeithas yr Iaith at the time, but also as the singer of ‘Carlo’ – the satirical anthem which poked fun at the idea of an English Prince of Wales, and described as a ‘Hymn of Hate’ by the Carnarvon and Denbigh Herald.

Ironically, given that he has on the receiving end of so much vitriol from royalists, Dafydd Iwan initially had reservations about the wisdom of Cymdeithas yr Iaith leading the public opposition to the royal circus.

Other leaders of Cymdeithas yr Iaith, such as Emyr Llywelyn, viewed the Investiture in symbolic terms stating that the political development of Wales had been cut short violently in 1282 with the death of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, the last native Prince of Wales.

Everything that happened after that was ‘an unnatural reversal of the nation’s development’. Similarly, the main question posed by the Investiture for the philosopher Professor J.R. Jones was ‘what had become of the sovereignty of the Welsh people?’

For activist like Gareth Miles, it was heartening that Wales, for once in its history, resembled other nations’ anti-colonial struggles – with a clandestine underground organisation, a student protest movement and a moderate nationalist party.

‘Change’

It was not a matter of trying to stop the ceremony from going ahead, however. Ffred Ffransis, who played a central role in Aberystwyth’s student protests, said that winning the battle at the time was not the key thing, but rather to show future generations that people had taken a stand: ‘That the people of Wales could say – There was opposition. Wales has changed. And it will be much harder for something like this to happen again.’

If one of the political aims of the Investiture was to undermine Plaid Cymru’s electoral progress in Labour’s heartlands, it can be said that it was only partly successful.

Although the Party lost Gwynfor Evans as its only MP in the 1970 General Election, the party did achieve its best ever share of the vote; and four years later, in the October 1974 General Election, they gained three seats from Labour, including the royal borough of Caernarfon itself.

In Cymdeithas yr Iaith’s case, the movement’s campaigns gained momentum and members’ resolve was hardened by the experiences of the Investiture protests.

1969 was a bitter and difficult year. But by standing against the inauguration of the son of the Queen of England as Prince of Wales, and all that event represented, the national movement regained some of the self-respect lost by the failure to prevent the drowning of Tryweryn.

Dim Croeso ’59 costs £9.99 and can be bought here.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.