Ideas as Sparkly as Coins – Jon Gower visits the studio of one of Wales’ most remarkable artists

Jon Gower

The studio sits at the bottom of ribbon terraces of houses in the Sirhowy Valley, in a neat whitewashed former chapel called Babell. The poet Islwyn was once part of the congregation and is buried in the tidy, cramped graveyard outside.

But what was then a simple Christian witness box is now a quiet temple to creativity, a place where, for the past quarter of a century David Garner has spawned remarkable ideas and made arresting objects, often at scale and always with depth.

Garner’s work usually connects quite intimately with where he grew up, in the tiny industrial village of Aberbargoed, a place with a junior school and a miners’ institute which was dominated by a coal tip like so many other communities.

“That square mile – whoever you are – impacts on you as person. I didn’t see my collier dad all that often as he always worked nights. I was the only child so there was a strong connection with both my parents, Dai and Violet.

“What they wanted most of all for me was to escape from this environment. They were wrongly made to think that that was a good thing and that what they were doing wasn’t worthy which is wrong.”

Garner’s coal-miner father Dai certainly didn’t want his son to follow him underground even though ‘it provided employment for thousands of people and provided a culture around it. When you take that way well, we know what happened…we now have four generations in the valleys who have never worked. It’s OK to criticize it, and yes the miners weren’t paid much money back in the day and my father didn’t get paid much but they were doing a job that was needed.’

‘The Hewer and the Sentinel’

Dai Garner worked fifty years underground, starting in Elliots Town in New Tredegar and then moved, as pits were closing, to Groesfaen in Deri and ended up in Bargoed where he spent twenty years working nights because it paid ten pounds a week extra.

After fifty years David’s father should have been given a gold pocket watch to mark the occasion.

“He’d started work at the age of fourteen but was made redundant at the age of 64, having worked for half a century. He therefore didn’t get his watch because he was one year shy of his 65th birthday.”

It made his son angry but his father was more phlegmatic. ‘Boy, what do I want a watch for?’ he asked, now that he no longer had to clock in to work every day. But it did rankle his son.

During lockdown Garner made a piece called ‘The Hewer and the Sentinel’ about this slight to his dad. He took a pair of actual miners’ boots, still with National Coal Board stickers on the soles and covered them in gold leaf so that they gleamed like something a seventies rock singer might have worn. He threw them over a suspended wire: when you approach them a little canary sings out from the heel, a little bird long associated with miners who would take then underground to warn of methane gas.

Another piece of art, ‘Undone’ involved a much simpler idea and was put together very swiftly. Also made at the beginning of lockdown, it involved his taking a pair of boots and threading a pair of laces through them which were huge, sixty foot long. ‘The laces were a hinderace – you couldn’t do them up and you’d still fall over despite them so they were pointless really.’

Once he had the initial idea that only left finding a pair of proper laces, 5mm round, with metal tips on them which were that long. So he found a company in the Midlands who made laces and cajoled them into running off a pair for him. They did so happily.

Pennies for the People

Another work was much more time-consuming to produce. ‘Pennies for the People’ took a long time both to research, produce and install.

“I saw a coin in the museum in Newport, a Chartist penny which commemorates the insurrection of 1839 when 22 people were killed and other arrested with some of those later transported.

“They took a penny of the time and engraved the name of one of the principal ringleaders on one side, ‘Frost’ and engraved the words ‘Set Him Free’ on the other and put them back in circulation, almost like the social networking of the day.”

Sixty five years later the suffragette movement did the same, stamping ‘Votes for Women’ on what was then an Edwardian penny, back in 1903. Garner decided to so something with these.

“We were in a time of austerity and I considered placing something to do with soup kitchens and food banks, bankers’ bonuses and so on onto a two pence coin and tried to think of an object that would pull all these together.” He struck on the idea of a chandelier, which symbolizes opulence.

He consequently made a four-tier chandelier which would carry two pence coins in rows of six, making over six hundred in total, all stamped with bilingual messages formed from individual letters which had to be made one at a time. “I would go work on them as if I was going in to a factory and it was laborious…you’d make mistakes and you’d have to throw things away and start again.”

Garner then pondered where to hang the chandelier and decided to take it to the cave at Trefil on Llangynidr Moor where the Chartists held their secret meetings, to install it there and thus light the space.

He then met the harpist Rhodri Davies who suggested playing an improvised piece in the cave in which he responded to the work, resulting in a film called ‘Call and Response.’ Garner wants the work to be seen rather than be sold, as he ‘wants to make something, which is a voice, and it’s my voice saying what I want to say in my language.’

This is the language of image, idea, shape, structure and colour. The work is always arresting whilst often being playful and always humorous, a constant trademark of his work.

Global audience

A personal disappointment for Garner has been Wales’ decision not to take part in this year’s Venice Biennale, especially as he’d been busily garnering support for an application to represent his country, including backing from international curator Sacha Craddock, the Chair of the New Contemporaries who had also been involved in the Turner Prize in 2017. “The Venice Biennale is probably the biggest opprtunity for an artist…to represent one’s country in Italy for six months, with thousands of people going through and hundreds of curators, you couldn’t get a bigger, global audience for one’s work really.

“Unfortunately Venice 2022 is going ahead, with 90 countries taking part but sadly not Wales for whatever reason. It’s a crying shame…to have an opportunity to take part in a global event and miss out, whatever the reasons.”

Political conflict

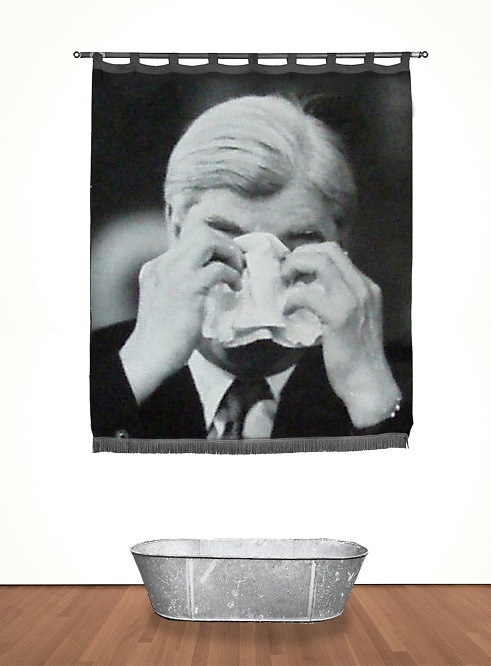

There is often a political side to the work but Garner suggests it’s hard for any artist not to be political. Garner is a ‘huge fan of Nye Bevan and why wouldn’t I be and I found this image of him where his face is hidden behind a handkerchief and it looks as if he’s wiping his eyes. It’s an image I haven’t seen anywhere else.’

The image lodged and he then obtained a copy and cleared the copyright. The resulting piece is called, unsurprisingly ‘Weeping.’

The original archive press photograph of Aneurin Bevan was taken at the Labour Party Conference at Brighton on the 30 September 1957. On the reverse of the image, along with the usual photographic agency stamps, are two comments: the first is a description, ‘Mr Bevan wipes his eyes as he listens to the speeches at the opening of the Labour Party Conference at Brighton today’; and the second is a quotation, ‘“It is no laughing matter”, says Mr Bevan opening the Labour Party Conference.’

The photograph has been enlarged to 8’x 6’ in the form of a trade union banner which Garner made with the help of London based banner-maker Ed Hall, who makes them in his front room and in a little shed out the back. The tin bath, set beneath the huge face, is filled with water suggesting tears shed by Bevan at the current condition of the NHS.

Bevan also inspired Garner to make a film about words and the wind. ‘The only two remaining speeches by Aneurin Bevan were sourced and then reconfigured into twenty-five segments, in order to emphasise the significance and stress the importance of the NHS and the need for a just society in the narrative.

This reconfigured audio was then broadcast on Llangynidr mountain, the place where Bevan would practice reading poetry aloud, in order to help counteract his stammer.’ Garner reminds us that Bevan would frequently climb the mountain with a stool and books, in order to overcome his speech impediment and in the film the speech comes into conflict with the wind and the weather, which is also suggestive of political conflict.

In the film white heads of cotton sedge flowers act as Bevan’s lonely audience. Meanwhile the pages of a book set on top of a pile flap madly in the wind, seemingly in time with the fluctuating pattern of Bevan’s speech. ‘Although these words were delivered over sixty years ago,’ says Garner,’ they are as relevant and critical today in their expression of the need for a fairer society.’

Authentic material

Garner is far from being a parochial artist and has many perspectives on the larger world. His work reflects on current affairs, often highlighting injustice or looking at the underdog, ‘so there have been several pieces about Palestine, basically highlighting wrongs that are going on in the world.’

He always strives to use authentic material, so when he made a great number of origami tanks to reflect on the events during the popular uprising in Tahrir Square in Egypt during the Arab Spring of 2011 they were made from leaflets actually handed out by protestors.

He came back to Wales during the miners’ strike and started what he describes as a ‘brilliant relationship with Caerffili County Borough Council’ who found studio space for him and has done so now for 25 years.

In return he then gives something back to the community such as visiting schools, created pop up galleries or inviting people to visit his studio. He’s currently giving free art lessons in the community centre in Cwmfelinfach which will run ‘until they don’t want it anymore’ and the take-up has been excellent, in double figures.

Garner is hugely grateful for the support of people such as Kevin Edon-Davies from the council’s countryside management team who has ‘championed me basically. He said to me that I’m basically the extension of the poet Islwyn – you’re providing culture in a different way to the way he did.’ Such practical help is invaluable to the artist, giving him the space to both generate his bold ideas and bring them fully into being.

Landmark piece

Of all the works Garner has produced over the years one that stands out for him is called ‘A for Aberfan’ which commemorates the tragedy when coal spoil engulfed the school in 1966. It consists, simply, of thirty primary school chairs.

“I was eight at the time,” recalls Garner “and I remember all the lorries going through Aberbargoed at the time to help. I saw images of the spoil which had come in through a window and settled on a desk.

“I had the idea of making little bitumen wedges and placing one on each chair. They were identical when I made them, but they’ve all changed over the years, becoming more individual.

“I hadn’t expected that change in the work and for me that’s been a landmark piece in so many ways.”

Like so many of his works they leave an indelible mark on the mind, which is probably his intention.

You leave Garner’s studio as if you’re stepping out of the Tardis, realising that hours and hours have simply flown by in his utterly engaging company.

Here is an artist for whom ideas are currency, bright and shiny as a Chartist’s coin, illuminating the world even as he does his level best to understand it.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Diolch Jon. Darn gwych. Dwi’n cofio gweld y gweithiau unigol ond buaswn i ddim wedi cofio enw David Garner, ysywaeth. Dyma waith sydd yn haeddu cael ei weld yn cynrychioli Cymru yn Fenis, yn ddi-os. Beth yw’r rheswm dros beidio â mynd yno bellach, wedi llwyddiant y blynyddoedd diweddar?