Interview: Writer Hefin Robinson on his new horror play ‘Pontypool’

Rhys John Edwards

When I first heard that Wales Millennium Centre were producing a new horror play set to premiere across Halloween, I was eager to hear more. But I soon discovered that the more you learn about Pontypool, the less you truly know.

Here, we have a play which was inspired by a radio play, which itself was inspired by a cult horror movie… which itself was adapted from a trilogy of novels published in the 1990s. Oh, and the ‘Pontypool’ of its title is actually Pontypool in Ontario, Canada, approximately 3500 miles away from Pontypool, South Wales.

In cash-strapped times for Welsh arts, writers are having to appease commissioners’ desperation for relevance and relatability more than ever, and yet, this theatrical reimagining of a niche Canadian horror story miraculously got its foot through the door. What a win!

Whichever way you look at it, unconventional plays like this are in no danger of becoming a common occurrence – ‘Catch it while you can!’ – has never been a more appropriate marketing tagline. Perhaps it’s fitting then that this project should have been brought to life by Hefin Robinson, who believes a defiant approach to playwriting was instilled in him from an early age.

‘My writing journey started at school,’ Hefin tells me ahead of Pontypool’s opening at Wales Millennium Centre. ‘I was really lucky to have incredibly supportive teachers in Carmarthen that encouraged me not to compromise and to always write in a way that allowed me to say what I wanted to say. That ignited a spark in me, I think.’

Retaining the Welsh language

Having spent most of his early career writing in Welsh language, a notable example of Hefin’s uncompromising commitment can be seen through his determination to retain elements of Welsh as he expands into English language work. Fortunately, the story of Pontypool lends itself extremely well to bilingual storytelling.

‘It’s a play that explores language in a really interesting way.’ He says. ‘As much as we’re using bilingualism as a form of representation of the language in Wales, what’s really fun is it goes a little bit deeper and becomes crucial to the plot.’

The cast is made up of a fairly even split between Welsh speakers and non-Welsh speakers, with lead actor Lloyd Hutchinson in fact, hailing from Northern Ireland. ‘Lloyd brings a completely different perspective. Recently, whilst we were filming the trailer, he was amazed how many in the crew spoke to each other in Welsh. It just doesn’t seem to be something that’s publicised that much outside of Wales – how alive this language is, you know?’

An unlikely prospect

Hefin agrees that on paper Pontypool seems to be an unlikely prospect to receive a commission from one of Wales’ leading theatres. He cites financial reasons for this, rather than a lack of imagination from arts organisations.

‘Because there’s such a lack of money, there’s a lack of work being made. I think, as a result, a lot of theatres are looking for something really specific and that has affected the freedom to be allowed to do something unique. Particularly, when it comes to horror…’

Hefin suggests that horror in theatre is usually reserved for the ghost story. Audiences may have come to expect something closer to The Woman in Black or 2:22, but this play leans away from ghouls and instead more towards themes of claustrophobia and even gore.

‘On the one hand it’s a really fun roller-coaster ride that will give you the tension and the jump scares and the dark humour and all the stuff you really want… like blood! But then, it is also tapping into something that feels relevant to today and speaks to our modern discourse, in particular, the way the media communicates and uses language.’

More relevant now than ever

And here is where you can start to see where the theatre’s appetite for relevance has been somewhat satisfied. At the centre of the play is ‘Grant Mazzy’, a character referred to in the original novel as a ‘shock jock’ – a persona which until recently was more familiar in the US and Canada but has since become more common here, as various disgraced media personalities seek to reinvent themselves by expressing headline-grabbing, forcibly controversial opinions in a desperate bid to retain the limelight.

‘The story feels more relevant today than when the original came out 15 years ago because now we do have these ageing media personalities…these incredibly opinionated presenters or influencers that have this sense of entitlement around what they can say. And we’ve seen recently how what they say can incite violence. It’s really scary.’

Hefin won’t be drawn on a specific inspiration for the character but does share that Mazzy is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster of a handful of personalities that will inevitably spring to mind’. I can certainly think of a few…

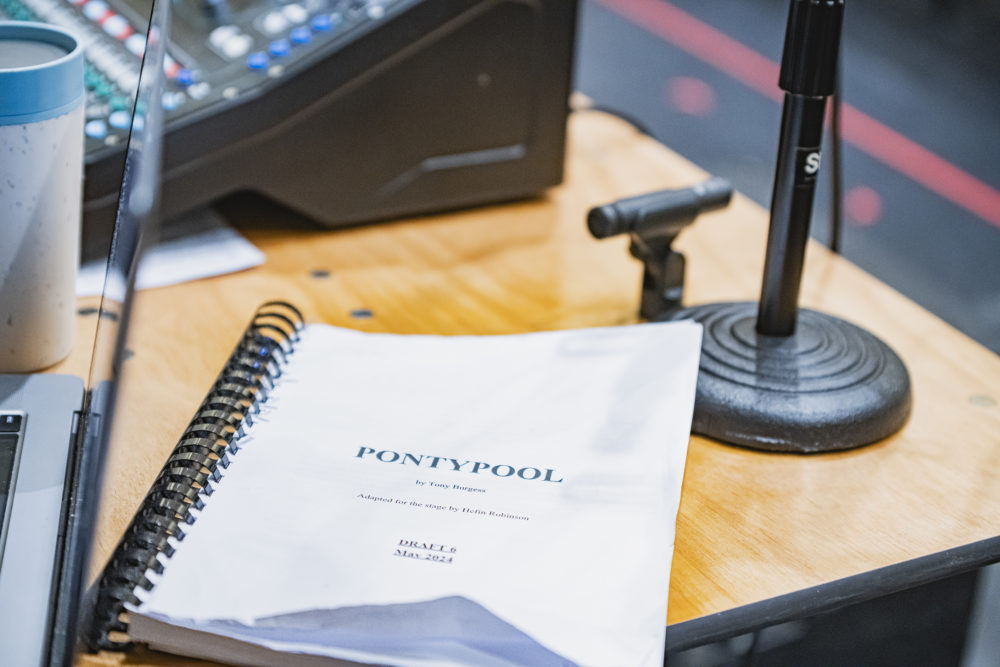

But the significance of radio isn’t mere zeitgeist fodder. The lack of visuals instead promote an intense focus on sound, which is crucial to the play.

Hearing the horror

‘Sound is almost a character in itself.’ Hefin explains. ‘You’re hearing the horror because we’re stuck in this basement radio studio. We have the presenter on air and suddenly people are calling in from out on the streets. We’re getting a perspective from lots of different people out in the town that… ‘events’ are happening.’

Hefin clearly doesn’t wish to spoil the many surprises in store but it’s a good sign just how excited he still is when alluding to them. Despite living with this play for a number of years, he talks about Pontypool as if he were a giddy fan queuing up for a ticket.

‘The sound is incredibly important in terms of building that tension and that simmering sense of… Oh my goodness, something awful is happening here!’

‘And we’ve got the most ridiculous sound system rig. I’ve never seen anything like it. It’s going to completely immerse the audience. It’s so exciting!’

For Hefin, the beauty of ‘hearing the horror’ is that what you see in your mind’s eye is inevitably more frightening than something physically taking place in front of you.

‘It’s like reading a book. You’re letting your brain do the work. And your imagination is far more terrifying than reality.’

Permission to have fun

I ask if he has any specific hopes for the audience reaction, presuming that scaring them is top of the list?

‘I like the idea of playing with an audience. Finding ways of telling a story that will surprise or shock. Theatre can be a bit snobby towards genre driven work, particularly things like horror or sci-fi, but genre often gives audiences permission to have fun. And I think that’s the most important thing.’

‘But…’ he concedes. ‘If we have managed to scare a few people along the way, then, yeah… I’ll feel like I’ve done my job!’

‘Pontypool’ is playing at Wales Millennium Centre from Friday 1 November till Saturday 16 November.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Pontypool (Wales) is actually an horror story, whereby a strategic town that played a big part in historic moments.

Now a SHELL that lacks any kind of strategy from its councillors (Labour) it is a ghost town and it hurts me to go there!

Yet it historically vote Labour and they have paid the Price!!!