John Cowper Powys and the spirit of Glyndŵr.

Jon Gower examines what happened when a genius novelist addressed the subject of Owain Glyndŵr.

The American writer Henry Miller believed that encountering the writing of the writer John Cowper Powys ‘is to arrive at the very fount of creation.’ Powys was described in the Times Literary Supplement as ‘a man possessed of superlative talent, or genius, or (the word is inescapable with Powys) demon.’ The Washington Post called him ‘a novelist of great, cumulative force and lyrical intensity’ saying that ‘Out of his rhapsodic style and keen attentiveness to nature, he builds a tower of prose to match the firmament.’ The novelist Margaret Drabble similarly reached for huge superlatives suggesting Powys is ‘like no to other writer…He rears up, challenging, like a great crag in a wild landscape. He is bold, inhibited and shameless.

In reaching for the mountain for her craggy metaphor Drabble joins the Welsh psychogeographer Iain Sinclair who said:

Powys cultivated this gift, the recognition of self in natural forms, to a higher peak that any other writer of his generation. He knew that these mountains are more than a geological accident. They cannot be explained in terms of upthrust and earth movement: the knife of ice. It is the biological kinship that interested him. That the hills contain the old gods, are moulded to the shape of their bones. And it was here, in the stereoscopic loops of this vision, that all the mythologies fused and became one, were taken into the swift bloodstream of Powys’s prose.

Parallel universe

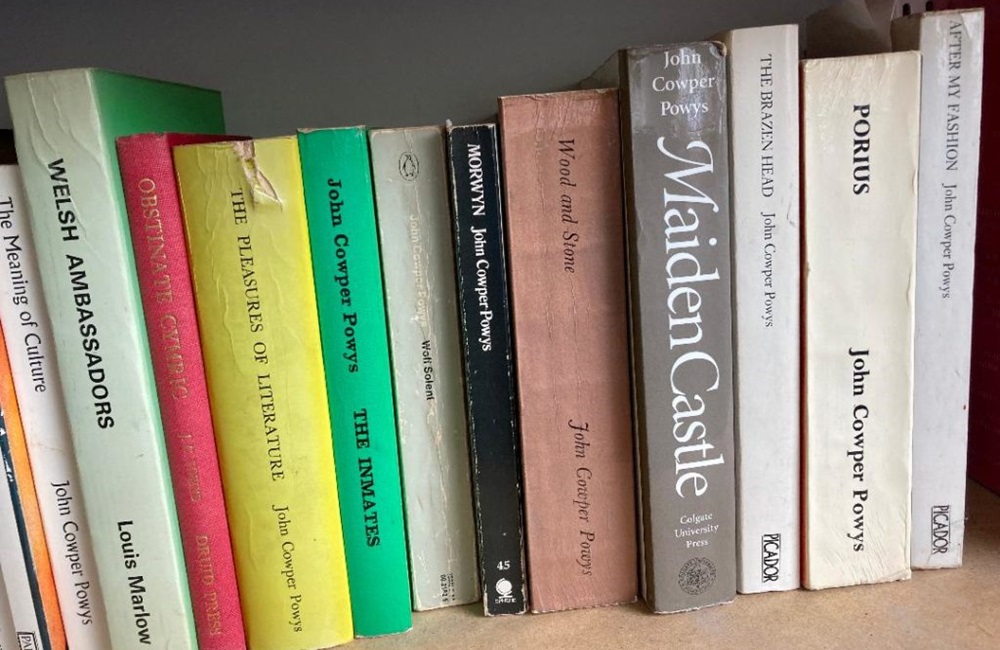

The novelist, poet, critic, and philosopher John Cowper Powys was born in Shirley, Derbyshire in 1872, the eldest son of the Rev C.F. Powys. On his mother’s side, he descended from the families of the poets John Donne and William Cowper while his two brothers, Theodore Francis and Llewelyn were also writers. Words were very much in the family D.N.A but in John’s case they poured out of him, an Amazonian river of them that resulted in twenty novels and a myriad streams of other writing. Margaret Drabble suggested the realm of John Cowper Powys is dangerous: ‘The reader may wander for years in this parallel universe, entrapped and bewitched, and never reach its end. There is always another book to discover, another work to reread. Like Tolkien, Powys has invented another country, densely peopled, thickly forested, mountainous, erudite, and strangely self-sufficient. This country is less visited than Tolkien’s, but it is as compelling, and it has more air.’

He was a late starter. John Cowper Powys did not start to publish fiction until he was in his forties. He was writing one of his biggest novels, Maiden Castle in Dorchester when is friend the novelist James Hanley and his wife Tim came to visit. They decided to help John and his wife Phyllis find a place to rent in north Wales.

Move to Wales

When John and Phyllis moved to Corwen in July 1935 they would not return to England and spent the rest of their lives in Wales. Powys had long been interested in Glyndŵr and as soon as he got to Corwen he began his mental mapping of the novel he was charting in his head. Almost every day he would walk to the top of Pen-y-Pigyn wood where he got ‘a wondrous view in the rich rain-soaked colours – browns & greens & purples – of the valley of Glyndyfrdwy & Carrog.’ On his local explorations he found a pillar in Corwen churchyard which he decided, rather fancifully, must be ‘the cross of Glyn Dŵr’s angry dagger.’ He and Phyllis took short bus rides to the Pillar of King Eliseg, to Valle Crucis Abbey, where Glyndŵr family poet Iolo Goch was buried, to Llangollen to view the ruins of Dinas Bran, the fortress of Bran the Blessed, a castle of which Trevor Fishlock once said that it was a place of such antiquity that even the Welsh don’t know its origins.

Powys also explored the banks of what he dubbed the ‘sacred river Dee’ and all the while he was recording and storing images; the way Welsh farmers dress – their ‘huge inner life-illusion of a dramatic appearance,’ the sun and mist wrestling with each other – ‘losing, winning, losing, winning over the Berwyns, ‘ or a column of smoke rising straight up ‘like an enchanted lily-stalk, the very large Mountain Ash with new leaves out of its death.’ But he didn’t start writing Glyndŵr’s story for another two years.

Gargantuan

When he did embark on what would become a gargantuan novel about Glyndŵr he wrote to the University Library at Bangor to ask if he could borrow the books necessary for his research. He was by now very much at home in Wales. Certainly, he wrote, ‘no lover of the historical, no lover of the mythological, could find a spot more suited to his taste’ especially as he was now living in the very landscape in which Glyndŵr had lived, fought and eventually died in.’ Writing is was far from easy. He and Phyllis were often teetering on the very edge of penury.

Moving to Wales fulfilled a desire John Cowper Powys had nurtured since he was a youth and after living in Corwen he moved, in 1951, to Blaenau Ffestiniog, where he died, on the 17th June 1963, aged ninety-one. He learned Welsh and corresponded with many distinguished Welshmen of letters; his non-fictional writings about Wales and the Welsh were collected in Obstinate Cymric (1947). He wrote three novels in this period including Porius which he thought his best and, of course the enormous, energetic, hugely imaginative Owen Glendower.

Parallels

An important aspect of Owen Glendower is the historical parallels between the beginning of the 15th century and the late 1930s and early 1940s. As the poet Herbert Williams put it, ‘A sense of contemporaneousness is ever present in Owen Glendower. We are in a world of change like our own’. The novel was conceived at a time when the Spanish Civil War was a major topic of public debate and completed on 24 December 1939, which of course was just a few months after the Second World War had started.

Owen Glendower, published in 1941, centres on the love affair between Rhisiart al Owen (a distant cousin of Glyndŵr’s and despite the title, Rhisiart is the novel’s true hero) and the beautiful red-haired Tegolin. It’s a book that had the great critic George Steiner in raptures suggesting that ‘Beside Owen Glendower, with its Shakespearean largesse of captured life, nearly all historical novels are charade.’ And it is a very big book, well over nine hundred pages – or as Powys counted them – a total of 336,856 words all employed to summon up a huge cast of characters. This is a very impressive output for a self-described invalid who survived on a skimpy diet of raw eggs, milk, and stale bread.

Powys wrote like a man possessed. Take a look at his manuscripts and diaries and you’ll see how the words tumbled out, waterfalled out in great gasps and gouts. With a writing pad set on his aged knees, as he himself sat propped up on a couch, he was a man ablaze with inspiration. As the poet and Powys biographer Herbert Williams describes him ‘His visions are dazzling, sometimes lurid, his words tumultuous and unsparing.’ As Williams goes on to say, extolling the virtues of a writer he obviously admires hugely, ‘The book is evidence of the colossal nerve and supreme self-confidence of a writer who feels the past is his to command and reshape. It is a Powysian past, made of the stuff of his genius.’ It all adds up, in the words of Jan Morris to being ‘One of the most fascinating of all historical novels about one of the most tantalizing of historical figures’.

Owen is a shape shifter of a character in the book. Owen Glendower also appears as Glyn Dwr and Glendourdy, as Owen ap Griffith Fychan, and as the Prince of Wales. Glendower, of course, is familiar as a character from Henry IV, Part One, albeit a Welshman portrayed as a comic character.

Owen Glendower is, in one sense, a book of stirring Welsh patriotism. ‘The Welsh,’ thinks Glendower’s cousin, ‘are certainly the most civilised people in the world.’ Powys’s Wales is not parochial, and its people are not barbarians. They are Oxford-educated, they know Rome and Avignon and Constantinople, they can read French and Latin, they debate theology and aesthetics, they ponder the future of the commonwealth and the universities and the coming rule of international law.

Glyndŵr himself is seen as a tall man with a yellow-grey beard and eyes of a ‘flickering sea-colour, sometimes grey and sometimes green,’ his forehead low and broad, his nose Roman, with unnaturally large nostrils. His cheek-bones are prominent, his cheeks ‘hollow and curiously white against his yellow-grey hair,’ his skin freckled rather than tanned by exposure to the elements. He has a courtly manner towards his guests, speaking in a voice so low that only the person being addressed could hear what he was saying. Only occasionally does Powys refer to him as Owain Glyn Dwr and the character he depicts is neurotic and introspective, even when he is declared Prince of Wales:

‘Long live Owen, Prince of Powys!

‘Blood,’ he said to himself. ‘Blood and ashes! That’s what this means.’

‘Long live Owen, Prince of Gwynedd!’

‘I’ll do it,’ he thought. ‘Nothing can stop me now. But to what end? There won’t be a castle in the whole of Wales in Harry’s hands when I’ve finsihed with him. But to what end?

After the novel ends John Cowper Powys adds an argument in which he explains where he got much of the novel’s history, trusting Sir J. E. Lloyd as what he describes as the safest authority on the documented events of Glyndŵr’s life. Lloyd tells us about his being a student of law at Westminster at the end of the reign of Edward III; and later as a knight-at-arms in the Irish and Scottish wars of Richard II. Then we have the key period when he was middle aged, between forty and fifty years of age when he quarrels with Reginald Grey, Lord of Ruthin and takes up arms against him, thus planting the seeds of what would grow to be a bigger argument.

Sir John Lloyd seems to think it doubtful if Glyndwr would have raised the standard of Welsh independence had he not been unfairly and unjustly treated in his fierce personal quarrel with Grey. Powys directs us to the final words of Lloyd’s biography, which can be taken as an indication of the position Glyndŵr holds, not only in the popular legends of Wales, but in the mind of a trained and judicious modern historian.

This is J.E. Lloyd’s summation: ‘Glyndŵr stands alone among the great figures in Welsh history in that no bard attempted to sing his elegy; this we must attribute, not merely to the mystery which shrouded his end, but also to the belief that he had but disappeared, and would rise again in his wrath in the hour of his country’s sorest need.’

In the novel Owen Glendower’s end comes after his briefly independent Wales has been crushed out and when he knows beyond doubt that his fighting days are over. In the novel he lives out his last days in the Powys-Fadog hills where his ancestors long dwelled.

This is how Powys describes those hills and the land and the way the Welsh relate to them: ‘The very geography of the land and its climatic peculiarities, the very nature of its mountains and its rivers, the very falling and lifting of its mists that waver above them, all lend themselves, to a degree unknown in any other earthly region, to what might be called the mythology of escape. This is the secret of the people of the land. Other races love and hate, conquer and are conquered. This race avoids and evades, pursues and is pursued. Its soul is forever making a double flight. It flees into a circuitous Inward. It retreats into a circuitous Outward.

You cannot force it to love you or to hate you. You can only watch it escaping from you. Alone among nations it builds no monuments to its princes, no tombs to its prophets. Its past is its future, for it lives by its memories and in advance it recedes. The greatest of its heroes have no graves, for they will come again. Indeed thye have not died; they have only disappeared. They have only ceased for a while from hunting and being hunted; ceased for a while from their ‘longing’ that the world which is should be transformed into Annwn – the world which is not – and yet was and shall be!’

Margaret Drabble’s review of a new edition of Owen Glendower, which came out in 2011, ponders Glyndŵr’s disappearance at the end of his days: ‘He requests that his body be burned on a funeral pyre, but that some fragments of his bones be buried beneath Corwen Cross, where they will preserve the spirit of the Welsh for ever. Thus the old hero with his forked beard vanishes into the folk memory of his race, knowing that it is unwise for a patriot to leave a corpse behind in the bunker.’

John Cowper Powys’ magnificent novel helps preserve the spirit of Glyndŵr and feed that folk memory even as he shows us the complexities of the age in which he lived. Owen Glendower is a monumental achievement which shows us what happens when a writer of extraordinary gifts couples deep historical research with the rampant energy of a wild imagination, an imagination described by Bernard Cornwall as ‘fertile, undisciplined and magnificent.’ Yes, truly, a magnificent imagination at work.

This article is based on a lecture given in the first Gwyl Glyndŵr Festival held in Moriah Chapel, Llanfyllin on the 14th September 2024.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

I have enjoyed his wwriting for nearly 50 years but is not easy reading.

What is the problem with pronouncing and writing Owain Glyndŵr’s name correctly? Who the hell was Owen Glendower?