John Peel and the fight for the future of Welsh language music

David Owens

This is both a history lesson and a love letter to the past.

The story of the rise of Welsh language music and the fight for its survival.

1986 was an important year for music in Britain. The underground was about to go overground and reclaim some lost ground.

The New Musical Express had coined the term C86 after a free cassette they had given away with one of their issues. It reflected an exciting time with independent labels and fanzines starting up at a rate of knots.

Bands like The Pastels, The Weather Prophets, The Soup Dragons, Biff Bang Pow, The Jasmine Minks, The Television Personalities, The Razorcuts, The Shop Assistants and labels such as Rough Trade, Postcard and Creation were reflecting a flourishing Do-It-Yourself scene that was gaining a head of steam.

And in much the same way the Welsh-language scene was about to undergo a radical explosion with a similar multi-styled, experimental approach.

On the frontline, facing down all-comers and flying the flag for the Welsh language was Rhys Mwyn. A fired-up iconoclast whose profligacy in organising gigs and publicity for his band resulted in much of the Welsh-language scene’s early profile being bulldozed by Rhys and his band, Bangor punkers Yr Anhrefn (The Disorder).

Their non-stop talking up of the scene made them the first point of contact for English music media interested in the cause. The band were something of an enigma, by virtue of their pioneering Welsh-language punk tirades and position as one of the hardest gigging bands ever. A normal year of touring would see them playing over 150 gigs, not only in the UK but also abroad.

In countries like Germany, France and Czechoslovakia, where there was not so much of a stigma attached to singing in Welsh as there was in the rest of the UK, they would regularly play in front of crowds of 500 plus. Anhrefn’s adrenaline-driven punk sound was as vociferous and persuasive as their championing of the Welsh music scene.

“As a teenager I was very cynical and hated everything Welsh,” recalls Rhys. “I saw the Welsh thing as being the Eisteddfod and shit folk music.”

But that all changed in 1977 when punk and two seminal Welsh-language bands turned his world upside down.

“There was a punk band from Llanelli – Llygod Ffyrnig and a new wave band called Trwynau Coch who set up their own indie label Recordiau Coch and released a single ‘Methu Dawnsio’. These were both played on John Peel’s Radio 1 show. I was 16 or 17 and was influenced by The Sex Pistols, but also these Welsh language bands who had released their own records on Peel’s show turned me on to the Welsh-language thing. I thought, cool – I can do that.”

With his brother Sion Sebon, and two of Rhys’s friends Gwyn Jones on drums and Sion Jones on guitar, Anhrefn’s vibrant punk manifesto and dynamic cottage industry were about to come alive.

“The key turning point was when we decided to put out our own records on Anhrefn Records,” remembers Rhys. “The first record was in 1984. Everything we were doing was influenced by fanzines, Rough Trade, indie labels all that culture. Our punk rock was very DIY. In Wales it was almost a necessity because we had no music industry.”

The second stage to this awakening of the Welsh language scene was the meeting of Anhrefn and Y Cyrff (The Bodies). The Llanrwst band were built around the punk ethic of their idols The Clash, and much like Strummer and co, they wore their heart on their sleeves with a punchy sound and an indomitable spirit.

Rhys: “I’d heard of what Y Cyrff were doing – putting on gigs and creating their own fanzine – and realised that we shared so many ideals, so I got in touch and we hit it off straight away.”

Inspired by Y Cyrff and Anhrefn, as well as the new productive DIY underground that had gripped the British music scene, a rash of bands were forming within thirty miles of each other in North Wales. There was the leftfield, off-kilter lunacy of Datblygu, the mercurial Gorwel Owen’s Kraftwerk-ish electro outfit Plant Bach Ofnus and the weird twisted pop of Y Fflaps.

“The common thread was we all realised that this was a new scene, and we were all mates, all at each others’ gigs, all gave each other support slots,” says Rhys. “So if Y Cyrff got a gig Anhrefn would get a support slot and vice versa. We had a fanbase and the gigs were selling out.

“It’s funny because the audience was full of people who have gone on to better things. There was Rhys Ifans in the crowd at one gig and Gruff and Dafydd Ieaun from Super Furry Animals in another. Then we thought, let’s put out our own compilations featuring all these Welsh language bands because it was much more cost effective than, say putting out 10 singles.”

Rhys remembers the day he first went to London to spread the gospel of Y Cyrff, Anhrefn and the Welsh scene to journalists and DJs, who were half-intimidated, half-impressed by his evangelical zeal.

“I went armed with copies of the first two compilations ‘Cam O’r Tywyllwch’ and ‘Gadael Yr Ugeinfed Ganrif’,” he recalls. “I went everywhere – The Face, Capital Radio, all the music press editors, I knocked on doors and demanded to be seen.

“I think they liked my cheek and started to write about us. Mick Mercer at Melody Maker who thought we were mad, David Quantick from the NME thought we were thugs. But we didn’t care, we were doing what we wanted. It was a home-grown thing, achieved naturally and done on our own terms.”

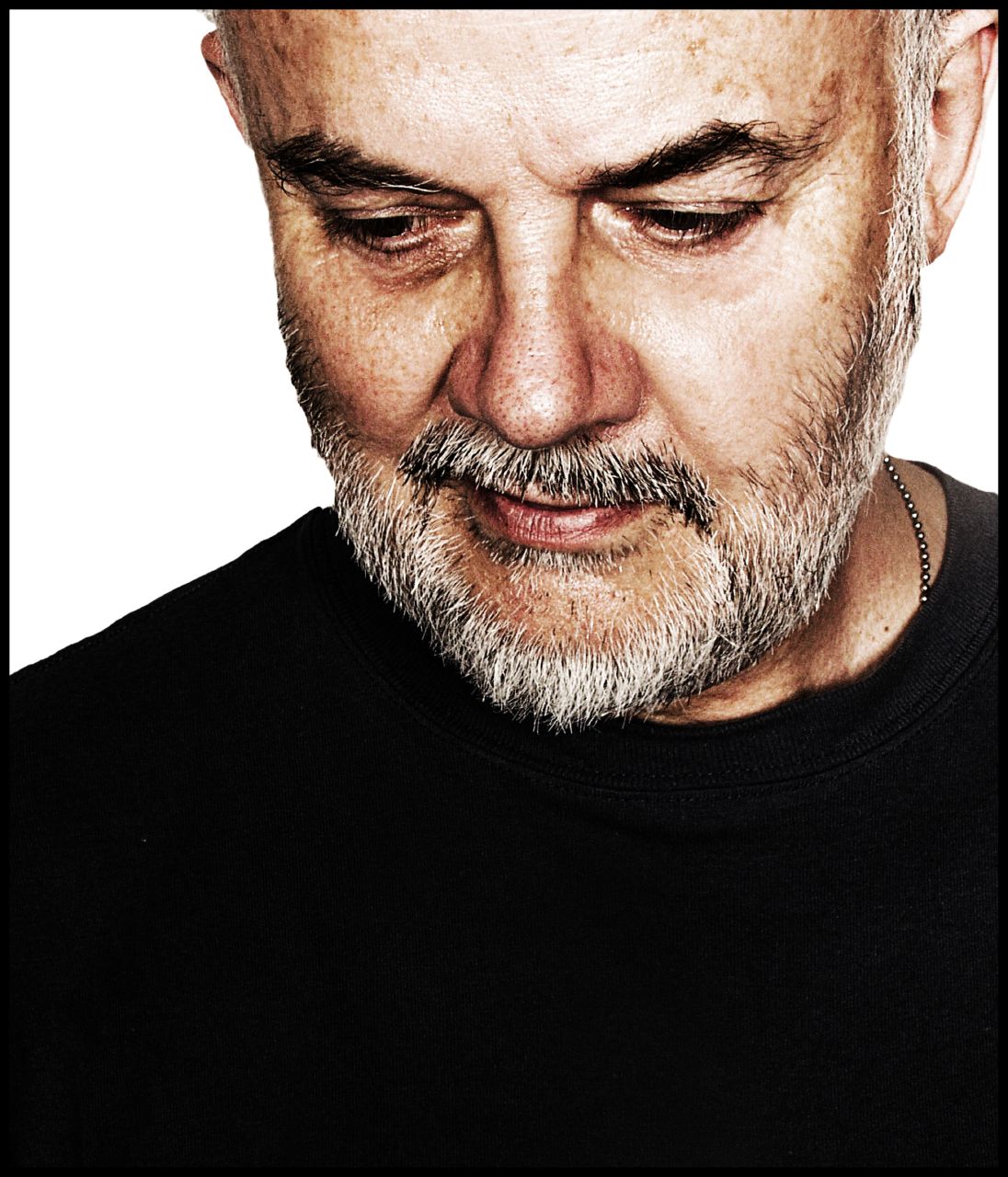

Legendary broadcaster John Peel was one of the first to meet the maelstrom that was Rhys Mwyn and a man who would become the main outlet for Welsh-language bands to be heard nationally.

Brought up in Shrewsbury, Peel had close links with nearby Wales from an early age. He went to a boarding school for boys in Deganwy in Conwy, and spent most of his military service on Anglesey.

But it wasn’t until Rhys Mwyn sent him some demo tapes of his bands, that the perceptive Peel began to realise that Wales had a music scene all of its own which was very much alive and well.

“Rhys had put together and sent me two worthwhile compilations on his own Anhrefn Records,” he remembers. “They were quite primitively produced in their way, because of the financial constraints the bands faced. However, when I eventually met Rhys, he was such a persuasive and dedicated person – the sort who just couldn’t be ignored – that he started me off on Welsh music. Before that I had zero interest.”

Europe

To Peel’s surprise, once he began playing Welsh records, requests started flooding in for Welsh songs from the most unexpected listeners.

Letters asking for more of the same arrived from people from Germany, Australia and Czechoslovakia, who all regularly picked up the show and enjoyed the music – even if they didn’t understand the lyrics.

“There is more of a language barrier facing Welsh music in the UK than there is abroad,” Peel noted. “In other countries, people are more used to listening to music in languages which are not their own, and they don’t see anything strange in it.”

But still the English media, in the main, remained strictly ambivalent. Save Peel and a double-page spread article in the now defunct music newspaper Sounds in 1988, the Welsh-language scene remained as underground to the rest of the UK as it was beginning to clamber overground in Wales.

A whole host of bands were excelling at singing in their mother tongue backed by an eclectic array of sounds and styles.

Journalist John Robb who wrote the article for Sounds, and who himself was a musician at that time with legendary Manchester noiseniks The Membranes, remembers the scene for its rapid diversity.

“’It was a rumbling collection of countless outfits creating a multi-styled assault of Welsh music.” says John. “There were the Fall-esque landscapes of Datblygu, the electronic weirdness of Plant Bach Ofnus, the twisted hip hop of Llwybr Llaethog, the techno indie pop of Ffa Coffi Pawb, the noise manipulators Traddodiad Ofnus, the indie weirdness of Y Fflaps and seemingly a thousand others.”

Apart from the seminal influences of Trywnnau Coch and Llygod Ffyrnig in the late ‘70s, up until this point the Welsh-language scene had been littered with middle-of-the-road rock bands and folk singers, but this rapid expansion reflected both a love of the music and the language.

“It was the first time the people who were directly involved were motivated as much by promoting the music as the language,” observed Y Cyrff’s manager Tony Schiavone, a full-time schoolteacher . “It was a very political time. We were promoting gigs through the (Welsh Language Society) Cymdeithas Yr Iaith, so for the first time a real support network existed with a number of venues for bands to play. There was a core of people who were very active like myself and Rhys and it was a very exciting and dynamic time.”

Anhrefn Records was then the main record label for bands wanting to release singles, having put out the first releases from Y Fflaps, Datblygu and the promising Heb Gariad. However, Rhys thought it time that more bands did it themselves.

“We had started to gig a lot in the UK and Europe, so the second part of the strategy was to say to these other bands you should put these records out on your own labels, let’s have more labels,” he recalls. “I remember having this conversation with Gorwel Owen, who went on to produce many of Super Furry Animals records. He set up Ofn Records and Ofn Studios, which became a home for Gorwel’s Plant Bach Ofnus and the bands Nid Madagascyr and Eiryn Peryglus, who both shared a similar experimental, maverick electro feel to Plant Bach.”

Y Cyrff too started up their own label and put out the self-released ‘Pum Munud’ (5 Minutes) in 1986.

With the Welsh-language music scene becoming both ‘rock ‘n’ roll’ and ‘sexy’, it invariably attracted the attention of Welsh-language media and new Welsh language channel S4C in particular. But at the time this attention wasn’t embraced comfortably by the bands who, with their strict underground agendas, were very suspicious.

Rhys remembers when Y Cyrff were the first Welsh-language band to get offered a TV gig.

“We all had a meeting to decide whether it was politically correct to do S4C,” says Rhys. “I said I think you should do it because it’s good exposure. We all had that underground thing, maybe we shouldn’t be doing telly, which showed how DIY we were. I mean it was a little bit Clash doing Top of the Pops. But if it brought the music to a wider audience all the better.”

Anhrefn in particular were masters of securing TV appearances – especially outside Wales. Particularly memorable is a testy chat with presenter Andy Kershaw on the Old Grey Whistle Test, where once again the band had to justify themselves singing in their own language

Meanwhile, back home Y Cyrff’s musical aftershocks were being felt all over Wales, but particularly in West Wales where two university students loved this strange and alluring Welsh band. Alun Llywd and Gruff Jones were two students at Aberystwyth University. They were promoting gigs at the student union and were huge fans of Y Cyrff.

These West Wales lads promoted gigs and published their own photocopied fanzine, Ish. But they also had grander plans.

“In 1988, Welsh pop music releases, with a few notable exceptions like Anhrefn and Ofn Records, were for the most part limited to recordings of choirs, old men and harps, and re-releases of wartime Welsh tenors,” says Gruff.

Not to be perturbed, the two students formed a partnership and one of Wales’s most important record labels, Ankst Records, was born. Leaving Aberystwyth, they relocated to Cardiff and with a close friend Emyr Williams, they set up the label in a damp one-room office, taking advantage of the limited funds the Enterprise Allowance Scheme had to offer.

For its formative years survival was on a shoestring budget.

“We used to wait for releases to sell out before being able to plough the small profits back into the next,” explains Gruff. “The early days saw cassette-only releases, progressing to 7″ EPs and eventually a host of 12″ singles. Although sales of Welsh pop releases continued to be low, there was great grassroots interest and plenty of potential.”

But it was in Cardiff at the television centre of Sianel Pedwar Wales (S4C) that one music show was at the eye of this revolution in Welsh-language music. Fideo 9 – so named because it allowed bands to make videos and have them shown on Welsh national television at 9pm on Thursday evenings – ran from 1988 to 1992. It gave Y Cyrff a regular platform for their majestic performances and fostered the careers of nascent versions of many of the bands that now sit serenely as Welsh pop royalty.

Fideo 9 saw the first sighting of a 15-year-old genius called Euros Childs and his strangely offbeat, neo-pastoral Gorky’s Zygotic Mynci. And then, Ffa Coffi Pawb, a psychedelic thrill pop machine featuring future Super Furry Animals Gruff Rhys and Dafydd Ieaun. The formula was simple but the results were startling. S4C in conjunction with the show’s makers, production company Criw Byw, allowed four bands every week to make a video.

Nothing earth-shattering in that, you might think, but which other UK music show was allowing bands access to state-of-the-art recording equipment, TV studios and a sizable payment at the end of it? Exactly. None.

Strangely there was no shortage of takers. “You could tell how healthy the scene was by the numbers of bands that were forming,” says Geraint Jarman, Welsh music icon and the show’s executive producer.

“When you had bands like Y Cyrff and Ffa Coffi Pawb appearing, they were influencing the kids who were their fans to form bands and not be afraid to sing in their mother tongue. It was a tremendously exciting time with a real sense of community between all the musicians.”

Musicians were not only afforded the sorts of gratis recording opportunities that most bands would have to save diligently for, but they were often taken on foreign trips to record videos and play gigs in Europe.

“We’d made connections with promoters in Europe who were sympathetic to Welsh-language music,’ Jarman remembers. “We took Y Cyrff to play Warsaw in Poland and they were awesome. I remember them supporting me and my band at a benefit gig in North Wales in ’86 and they were very frenetic, very fired-up, just like The Clash. But now they had quickly developed into writing amazing songs full of depth and feeling.”

Another band that were a product of Fideo 9 was Cardiff’s Y Crumblowers. If Y Cyrff were the artful Welsh existentialists, literate deep thinkers shrouded in a cloak of navel contemplation, then Y Crumblowers were 24-hour party people – a rumbling, tumbling, carousing confection of The Stone Roses and The Happy Mondays. Their gigs were parties and their parties were usually gigs.

In Cardiff they accrued legendary status. Gigs at Clwb Ifor Bach were always riotous assemblies. Like The Happy Mondays’ Bez and The Stone Roses’ Cressa, they also had their own dancer – Knocker (Sion Lewis).

In the space of a few years in the mid to late ‘80s the scene had become something of a juggernaut – an unstoppable vehicle for the impressive talents of independently minded bands and musicians who were taking the Welsh language overground.

It was a heady time when the foundations were laid for what was to come in the ‘90s when bands like Y Cyrff, Crumblowers and Ffa Coffi Pawb, in embryonic form would metamorphosize into Catatonia and Super Furry Animals – key players of the scene that would be dubbed Cool Cymru.

However, it’s thanks to those trailblazers that came before who allowed the Welsh language to become a musical force to be reckoned with. People like Rhys Mwyn and John Peel whose formidable drive and energy gave Welsh language music purpose, integrity and credibility.

To all of those who came before we should be forever grateful.

If it wasn’t for the expansion of the Welsh language scene in the ‘80s, we wouldn’t have the incredibly vibrant and dynamic scene we have today.

Diolch pawb.

The quotes and stories in this piece first appeared in the book ‘Cerys, Catatonia and the Rise of Welsh Pop’ by David Owens

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Brilliant welsh is the language of wales 🏴

Welsh and Wales, not welsh and wales.

Why did Welsh-language musicians take so long to start playing rock and roll (in the broadest sense of the term)? They seem never to have picked up on Elvis, The Beatles and The Stones in the late fifties and the sixties. If you bopped to the dreary MOR Welsh-language pop that was played on Disc a Dawns.in the seventies you had to be a pretty sad (to use an anachronistic term) teenager.

Mae’n rhaid ei fod rhywbeth i’w wneud efo agweddau pobl ifainc ar y pryd. Efallai nad oeddent yn meddwl bod cyfleoedd ar gael iddynt. Darlledwyd Disc a Dawn o 1967-73. Daeth roc i’r iaith Gymraeg tua diwedd yr adeg yna. Dwi’n nabod digon o bobl oedd yn leicio roc Cymraeg y 70au, a chofia, y gerddoriaeth fwyaf poblogaidd trwy’r ’60au ar y cyfryw oedd ‘easy listening’.

Gyda llaw, cyhoeddwyd y llyfr yma yn 2000, felly nid yw’r erthygl newyddion cyfoes o unrhyw ffordd.

Go back a dozen years…anyone remember Bran?

Great article!

Superb article, fascinating, diolch to all concerned!

Interesting & informative article! I thoroughly recommend Rhys Mwyn’s autobio “Cam o’r Tywyllwch” which is full of stories from those times. Two points I would make – the cradle of Yr Anhrefn was not Bangor, but Maldwyn (Rhys & Sion Sebon being from Llanfair Caereinion, and apparently the appearance of the punk band Crass in a local hall there was one of the seminal events for the young Rhys & Co. Secondly, it’s just not true to imply that all Welsh language music up to 1988 was folk & bland generic stuff – there was actually plenty of hard-edge stuff… Read more »