Last Man Standing: Redefining the life of Gruffydd ap Gwenwynwyn

Charlie Ieuan Leah

For centuries, Gruffydd ap Gwenwynwyn, the Prince of Powys, has remained in the shadows of Welsh history —mentioned, perhaps, but not explored nor understood.

Overshadowed by more iconic figures like Llywelyn the Last and Owain Glyndŵr. His legacy has often been reduced to that of a traitor, the prince who sided with the English crown at a critical moment in Wales’s struggle for independence. But history, as we know, is rarely so simple.

Gruffydd’s relationship with Llywelyn the Last was far from straightforward. In 1257, Gruffydd refused to recognize Llywelyn’s overlordship and was driven from his lands as Llywelyn sought to unite Wales under a single ruler. However, just six years later, Gruffydd returned to Powys as Llywelyn’s vassal and most powerful native ally. For a time, the two worked together, focusing on harassing the Marcher lordships that threatened their grip on Wales.

Gruffydd’s importance is evident by his role in the Treaty of Montgomery in 1267—an agreement between Llywelyn and King Henry III that marked the height of Llywelyn’s power. Gruffydd topped the list of witnesses to this treaty, emphasizing his status as Llywelyn’s most trusted vassal. Yet, cracks began to appear in their alliance as Llywelyn’s rule became increasingly autocratic, marked by suspicion and a tightening grip on his allies.

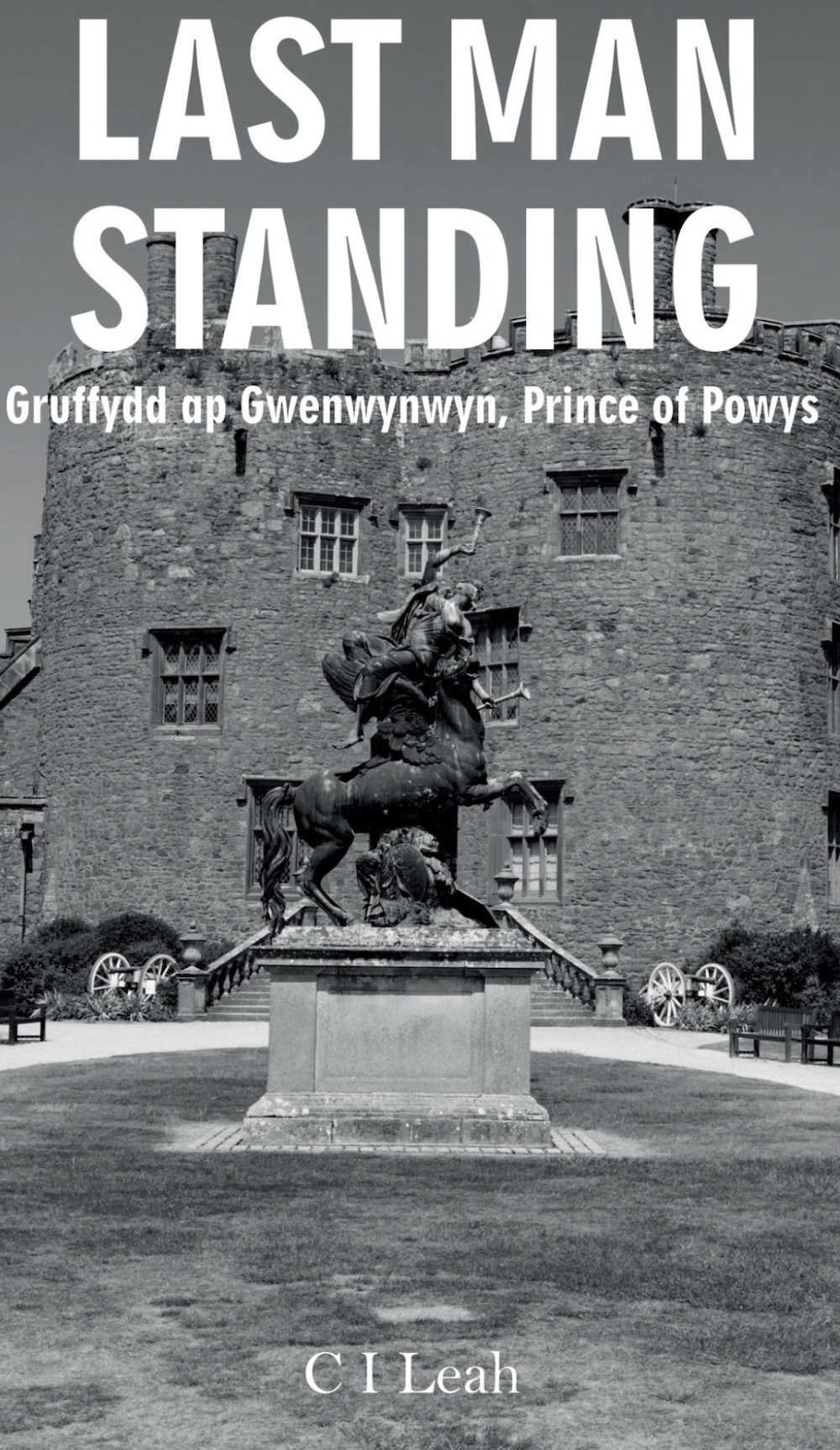

By 1273, Llywelyn’s growing interference in Mid Wales, his refusal to pay homage to the English crown, and the construction of Dolforwyn Castle—a military and economic threat just a stone’s throw from Gruffydd’s Powis Castle—began to suffocate Gruffydd. Dolforwyn symbolized Llywelyn’s dominance over the other Welsh princes and threatened to divert trade from Welshpool, a market town Gruffydd had spent decades developing. These pressures ultimately led Gruffydd to take drastic action: an attempt on Llywelyn’s life.

Though the plot was foiled by bad weather, Llywelyn remained suspicious of Gruffydd but unaware of the attempt on his life. In 1274, at a sham trial at Dolforwyn, Llywelyn stripped Gruffydd of parts of his lands and took his eldest son as a hostage. Later that year, Gruffydd refused to appear before Llywelyn in North Wales and fled to England. Backed by the English crown, Gruffydd launched relentless raids into Powys, aiming to erode Llywelyn’s hold on the lands he once ruled.

In 1277, war broke out between King Edward I and Llywelyn, and Gruffydd was restored to his lands. While Llywelyn was forced to submit, peace was short-lived. Llywelyn’s brother Dafydd, who had once aided Gruffydd in the plot against Llywelyn, sparked a fresh rebellion in 1282, reigniting war between Gwynedd and the English crown. That same year, Gruffydd found himself standing on the opposite side of the battlefield from Llywelyn near Builth Wells, where the prince met his end. With his death, the final hopes for Welsh independence were extinguished for nearly 120 years.

But this is the traditional story—one that paints medieval Wales in stark black and white terms: Welsh versus English, freedom fighter versus occupier. Gruffydd ap Gwenwynwyn’s loyalty to the English crown was shaped less by ideology and more by political survival.

The Welsh princes were frequently at odds with one another and marked by long-standing rivalries They fought each other as fiercely as they fought the English, and alliances were constantly shifting. From 1066 through the early 12th century, the princes of Powys played a crucial role in defending Wales from Norman expansion. Yet during this period, Gwynedd repeatedly aligned itself with the English crown—refusing to aid Powys during times of crisis, and sometimes even providing troops for English campaigns. This created deep mistrust between the native dynasties.

Gruffydd’s father, Prince Gwenwynwyn ab Owain of Powys, had been driven into exile by Llywelyn the Great, forcing young Gruffydd to spend much of his formative years in England. He would not return to his homeland for 25 years, aided only by the English crown. This moment serves as a poignant reminder that by the 13th century, it was often the English monarchy—not Gwynedd—that acted as Powys’s more reliable ally.

For Gruffydd, loyalty to the crown was shaped not only by political strategy but by personal history and a long memory of betrayal. As historian David Stephenson once concluded, “To charge those who resisted subjection to Gwynedd with acting as traitors is to accept without demur the Venedotian claim to dominance and at the same time to misunderstand one of the most powerful dynamics of medieval Wales.” It’s important to remember that Llywelyn the Last had not seized the mantle of Welsh leadership by consensus, but by force and domination. Gruffydd had already been the victim of one North Walian prince’s imperial ambition; he was not about to bow to another.

Last Man Standing: Gruffydd ap Gwenwynwyn, Prince of Powys attempts to redefine the legacy of a man often cast as a traitor in Welsh history. By exploring the complexities of his decisions—his strained relationship with Llywelyn ap Gruffydd, the fractured nature of Welsh princely politics, and his family’s longstanding conflicts with Gwynedd—this book offers a more nuanced view of Gruffydd’s role in a turbulent time.

It shines a light on the important, yet often overlooked, history of Powys—a principality that played a critical role in defending Wales against the Normans, only to be overshadowed by Gwynedd’s dominance in the 13th century. By reexamining Gruffydd’s actions through the lens of his personal and political context, the book invites readers to reconsider his legacy—not simply as a villain, but as a figure shaped by survival and circumstance.

Last Man Standing: Gruffydd ap Gwenwynwyn, Prince of Powys by CI Leah will be available on Amazon on May 21 2025

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Comment approved but now gone?

The book is too easy on Gwenwynwyn & too hard on Gwynedd. Internecine stife is a normal prelude to nation building: the AngloSaxon kingdoms did it. A Mercian ruler sent an assassin to bump off his East Anglian rival. The hero of Scottish independence – Robert Bruce – murdered his rival Comyn inside a church, so it is somewhat naive to criticise Gwynedd for not aspitiring to Welsh leadership through “consensus”.

Agree with the majority of what you have to say Martyn! The book wants only to highlight and reason with Powys’ questionable behaviour during the period. It considers WHY Gruffydd ap Gwenwynwyn was unwilling to cooperate towards a singular Welsh state, as opposed to attempting to justify his actions. That, as I state in the book, is for the reader to decide. I am just the messenger! Being a native Powysian, I want to lend an ear to an area of Wales I believe has been neglected in favour of the Gwynedd princes (though not to neglect their significance either),… Read more »

Walking the Lurcher through Powis Park one day years ago a rabbit ran straight into his mouth and with a snap of the jaw it was gone.

I don’t know who was more surprised, me, the dog or the rabbit, because the dog had never engaged in this type of behaviour before…

The 8th Earl I remember as a very nice chap, it was a conversation over lunch that resulted (eventually) in me taking a Hanes Cymru course in Aber…

A Road to Chirbury conversion…