Letter from Cambrians (Otago, New Zealand)

Hayden Williams

I’m seeking a small piece of Wales in the midst of Te Wai Ponamu, New Zealand’s South Island. Driving, I cap a hill, and see endless undulating fields, like scorched golf courses. There are creeks and ditches, ponds, wild ducks. The sunburned fields give way to tussock, grazed by filthy sheep. Far to the west, snow covered peaks are vague as cloud.

To the north and east lie the Maniototo, the ‘plains of blood,’ ridges continuing ever onward, the corrugations of a seemingly endless sea. I’m quickly made microscopic, lost in it like a mite in a vast carpet. Everything recedes to distance, ending blue and faint as the smoke from burnt off stubble.

The ancient land persists beneath a skim of cultivation, fences, imported trees and hedgerows. The land remains, almost outside time, shrugging up hills in a gesture of indifference. At times it reminds me of Brecon, back in Wales. Did the first Welsh settlers, who came here over a century ago, make similar comparisons?

The car returns to the space-time continuum: I arrive in the preserved historic mining village of St Bathans, but feel as though I’m stepping from Doctor Who’s Tardis. I park in front of the Vulcan Hotel – built in 1882 – and walk amidst the original stone cottages.

This place was called Dunstan Creek when officially founded in 1863, but it was renamed by Welsh and Irish gold-miners after a ‘Mr William Williams and the Swinney Brothers’ struck gold here, at the junction of Dunstan stream and the Manuherikia River.

The first settlers of the Otago gold rush requested the name be changed back to the original title, which the first surveyor in the area had given it: St Bathans.

I used to wonder if the surveyor had some connection to the village of St Athan, Bro Morganwg, or the saint which that village is named after, Saint Tathan. But Otago was predominantly a Scottish settlement.

It’s far more likely this St Bathans was named after Abbey St Bathans, a village in Berwickshire, Scotland; the long-gone abbey there was dedicated to Saint Bathan (Baithéne mac Brénaind in Scottish Gaelic), who was, according to Wikipedia, the second abbot of Iona.

What is certain is that the Welsh who were drawn here later abandoned St Bathans when a large influx of Irish people began to arrive. And eventually, most of the Irish left too.

There were about 1000 people in St Bathans in 1864, but more recently, before big numbers of tourists started coming, there was barely anyone here.

Many moons ago, the local bard Brian Turner walked into the bar of the Vulcan and reportedly found a note sellotaped to one of the taps: Gone fishing, help yourself.

Exodus

The often pious, non-conformist Welsh didn’t approve of the Catholic Irish who began flooding St Bathans at the time of the gold rush, nor the perceived depravity they brought with them.

Quickly outnumbered, the Welsh embarked on a four-mile exodus to ‘Welshman’s Gully,’ where Mssrs John Morgan and Thomas Hughes had staked a new claim.

Morgan (a collier, born in Garn Fach, near Nantyglo) and Hughes (registered as a collier and hauler in the passenger’s register of the ship he sailed out on, and born in Carmarthen) had dug a mine, which came to be known as the ‘Never Fail Mine.’

The mine was so successful that Morgan and Hughes’ efforts soon officially became the Vinegar Hill Mining Co., employing about a dozen men. There was a hydraulic sluicing operation, sluicing gold from diggings along the stream, along with a steady side-line in low-grade lignite coal which was mined nearby.

The village of Cambrians (also sometimes written as ‘Cambrian’) grew up around this business as the miners and their families built themselves mud-brick cottages. The community’s spiritual needs were catered to by Owen Owens (I don’t know if he was ordained or not).

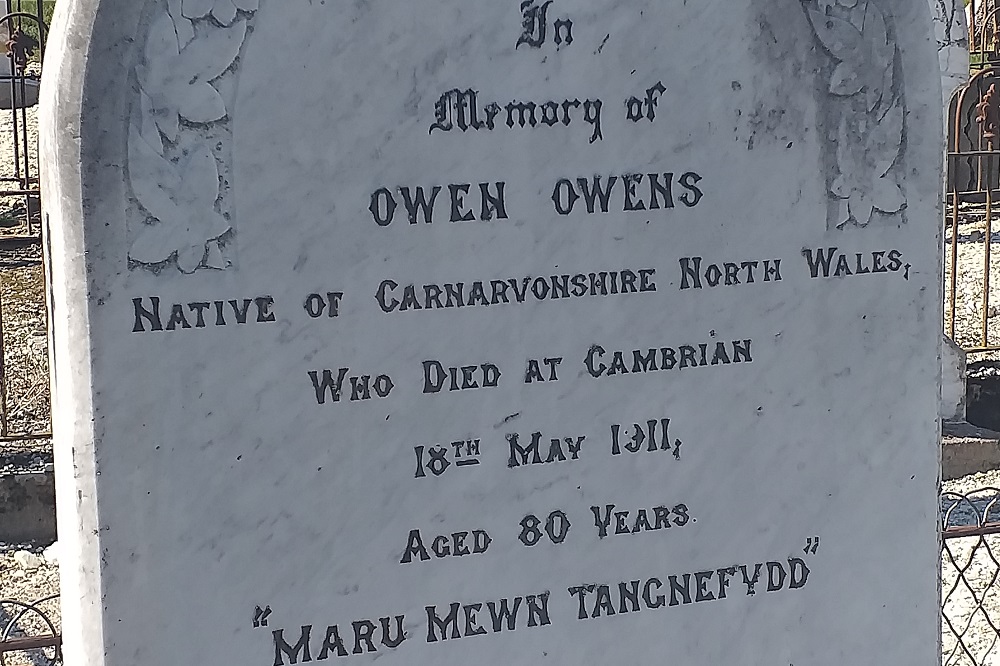

Owen Owens, “a native of Caernarvonshire,” according to his headstone, offered regular Welsh-language services in a ‘calico chapel.’ This was a large tent or marquee, pitched like the tabernacle in the wilderness.

A 16-room hotel — The Welsh Harp — was soon added. Owen Owens’ chapel became a wooden church in the 1870s. Despite most of the miners being illiterate, the church doubled as a village school.

According to history compiled by John Morgan’s descendant, Thomas L. Morgan, in his book Aur Y Cymro, John Morgan built a large ‘homestead’ slightly away from the village at Two Mile, near Vinegar Hill.

Two Mile, an area between Cambrians and St Bathans, was named after a marker stone which served to indicate the half-way point between the two villages. In effect, this stone marked an important boundary, because initially there were several skirmishes between the Irish and Welsh.

The Vinegar Hill near Cambrians was named after a hill in County Wexford, Ireland, where a memorable battle took place in 1798. The hill near Cambrians is said to have been christened in comic reference to some long-forgotten clash from this early period of feuding.

Down the years, animosity was civilised into a highly unorthodox and presumably very bruising annual rugby contest, of sorts. Every year, Two Mile would become the half-way line, and the ‘rugby’ game would kick off from there, terminating in the bar of either The Welsh Harp or the Vulcan, depending on who lost.

This on-going rivalry was known locally as ‘the war of the roses,’ but eventually relations between the two villages became civil enough to hold a combined annual fair on St Patrick’s Day.

Remains

Cambrians is miles from anywhere, and not on the way to anywhere, a settlement of some fifteen buildings. These are now mostly deserted holiday homes, though a few residents are permanent. Locals are proud of their village’s history, which is fairly unique in the whole of New Zealand.

Y Draig Goch is seen on gateposts and mailboxes. The Welsh flag still flies from flagpoles here. Some original cottages have been maintained, chimneys still smoking, iron roofs clenched against the cold.

The remains of other cottages aren’t too hard to find in the surrounds. Homes where the walls once held the sound of voices speaking Cymraeg, now yellow mud-brick ruins, abandoned and stripped.

Melted by years of rain, the chimneybreasts of the ruined cottages rise from the tall, blonde grass like termite mounds, like arms raised by the drowning past. John Morgan’s original homestead was reportedly still there at the beginning of the 20th century; by now, it’s completely dissolved.

The Welsh Harp is long gone, too, but Owen Owens’ former church and schoolhouse is miraculously still there. It now functions as a community hall and museum. It has a steeple, a hefty bell out front, and a tree not yet capable of shading it.

Inside the school’s porch-way, someone’s set up a library. There’s a clean jam jar for donations, trustingly left on the sill above a few dog-eared novels. A sign taped to the inside of the window reads: ‘Cambrians Book Exchange. The way it works: Bring a book – Take a book.’

The community museum includes a list of rules for Cambrians school teachers, written in 1872. Female teachers who married or engaged in “unseemly conduct” would be dismissed, whereas male teachers could take an evening off a week “for courting purposes,” or, “two evenings a week if they attend church regularly.”

Teachers who worked ten-hour days earned themselves the right to sit down, relax and read the Bible. However, any teacher who smoked, used liquor in any form, frequented public halls, or ostentatiously got himself a shave in a barber shop, “would give good reason to suspect his worth, intention, integrity and honesty.”

The school had at some point been moved to Becks, a village just a couple of miles away, where the residents had plastered it with a thick coat of daub and painted it bright pink — perhaps to disguise the origins of their new acquisition?

When the folk of Cambrians and members of the Historic Trust retrieved it years later, they peeled away the plaster and found the original wooden weatherboard intact underneath, perfectly preserved, a perfect repository for commemorating those who once lived here, long ago.

Tangnefedd

Rabbits scatter, their white tails bouncing off as I find the stream which the Welsh settlers mined gold from. It’s little more than a trickle of snowmelt over a bed of loose rock, flowing into a wide, wind-frilled pond, ringed with reeds.

Bob Berry, a white-bearded eccentric local who came here as an alternative-lifestyle-seeking hippy in the Seventies, has styled this pond as the village fountain. A hose rises at the centre, offering a comical spout beside a half-submerged bicycle.

Upstream, at one end of the village, Bob’s planted and nurtured a grove of silver birch trees — the village’s ‘common forest’ — now fully mature, its sun-dappled floor bright with bluebells and snowdrops.

Further upstream again is what must be the last farmstead of the Maniototo — a tiny white blip under the towering foothills of the Dunstan Mountains. This is likely the farmstead built later by John Morgan, who eventually traded mining for farming. Only swallows live there now.

At the other end of the village, there’s a grassy mound with a mysterious grave, a square of picket fence around it. The original wooden plank which served as a makeshift headstone is inside, detached from the grave, leaning against the fence. It’s been worn smooth by the years. The memory of whoever lies here has been erased by time.

There was a whole cemetery here once. The miners’ diggings came so close at one point that seven bodies were accidentally exposed and had to be reinterred. Eventually, all the graves here, except this one, were exhumed. The bodies were ironically taken along the road to St Bathans, and reburied at the official cemetery there.

The Morgans are there, along with Owen Owens, far off from any hardship or warring now. Sometimes, full of hiraeth, I’ve packed food and water, filled the car with petrol and cranked up the music, to go there, to see the place again, and to just say hello to the graves again, like a mad person.

A friend’s parents now own what was Owen Owens’ cottage. A century after Owen Owens’ death in 1913, I slept in the house he peacefully expired in. The friend and I got sunburned cycling along the road to the cemetery the following day.

There was silence but for gentle birdsong, gorse flowering brilliant marmalade. On the old minister’s gravestone, the words “maru mewn tangnefydd” [sic] (“died in peace”).

That word, ‘tangnefedd’ (a deep and true ‘peace’), now haunts my memories of Cambrians in a happy way. On windless summer days, when the sun is strong, and the tall pines at the foot of the graveyard’s slope are completely still, that word, set in stone, and somehow echoed in the immaculate blue of a huge sky above, seems the profoundest, most wonderful prayer.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Diolch, for this story. I appreciate your word skills!

Diolch i chi, glad you enjoyed it 👍