Letter from Church Village

I could not be a poet without the natural world. Someone else could. But not me. For me the door to the woods is the door to the temple.

Mary Oliver, Upstream: Selected Essays

clare e. potter

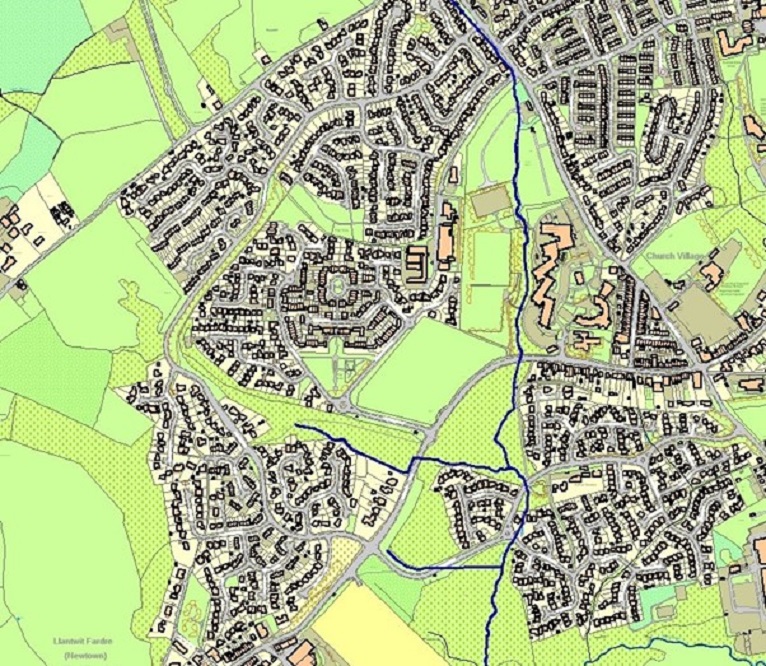

I live in the middle of a housing estate, brick after brick after brick, ironic streets named for trees and woodland animals. We’re wedged between the bypass and the old road where my grandparents charabanced from the valleys to Bari Island during the miners’ fortnight.

Though I’ve been here for 16 years, I don’t feel at all of this village, but that I am merely on a long-passing-through; that is, unless I’m here in the woods, the portal to calm and a belonging that demands no roots.

In the middle of the Dan Y Deri housing sprawl is this pocket of ancient woodland with a path that runs to the local school.

We’d walk the path, me and my two, my boy with a stick whacking dandelion seed heads, picking up good shaped stones, clambering up trees, my daughter singing or asking a myriad of questions, her little mouth anticipating the raspberries that everyone else seemed to walk past.

After school, he’d be in the thickets here, my son, with his friends, adventuring, making dens, getting mucky. I’d call him on his walkie talkie to summon him for tea. But I never really went in, only through these woods.

Lockdown changed all that.

It came shortly after an interview for ITV news where me and my two children were filmed for a piece on mindfulness right in these woods.

Me sitting with my back to the ash tree (where I’m writing now), my children jumping up the banking, sliding back down.

We’d talked about the importance of nature, about being and discovering, slowing down. My children’s play sounds, the birds, the river speckled with rain; that moment forever part of the woodland’s under story, and ours.

We’d gone in as a family that day and it was as if a mysterious door had opened up, offering this place for us, a solace from a soon to be frightening world; we went every day during lockdown.

It’s where my daughter learned the words wood an-em-on-e, celandine (we’d go at dusk to look at the flower heads closing); we spent hours in here, fishing out broken bits of crockery, me reading, my son whittling a stick.

We even found a piece of a bottle from the old cottage children’s home, learned that it’d been on the site where their school now was—the river nudging us into the past, giving up messages of lives once lived. We have boxes of river pottery now, enough to make a path of our own.

Winter 2021, Covid knocked me for six, after which I struggled with work and home, anxiety and exhaustion. I didn’t see friends so much, felt unable to exercise, found myself dreaming of sloths.

My children are old enough to walk themselves to school so I’d stopped going into the woods, but one morning, the late summer sun hit my mirror and I knew what I had to do before I talked myself into an excuse: I made a cup of tea and put my coat on over my nightie and went directly to the woods.

I wellied up the river and sat down on a boulder in the middle of the gentle flowing water.

The light speckled the forest floor, the river glinting, a warmth began in me and almost tears for how long I’d allowed myself to not come into these woods.

I’ve facilitated countless wellbeing and nature workshops over the past few years, encouraging people to find somewhere like this, somewhere outside the room, the house, their heads: a bench in the park, the sea front, a view of a hill through a window, a poem. Yet I’d been denying that for myself.

Well not that summer day as I sat there, a part of the river, the river I did not even know the name of in the woods I did not know the name of.

After remembering how powerful a medicine this place was, I started to come regularly to read, to write, to just sit and (not)think.

In the same way I’d pointed out plant and tree and bird names to the children (we’d watched a wren in and outing a hole in the river bank, found a heap of goldfinch feathers), I felt a longing to know the name of this woods that I’d become so familiar with.

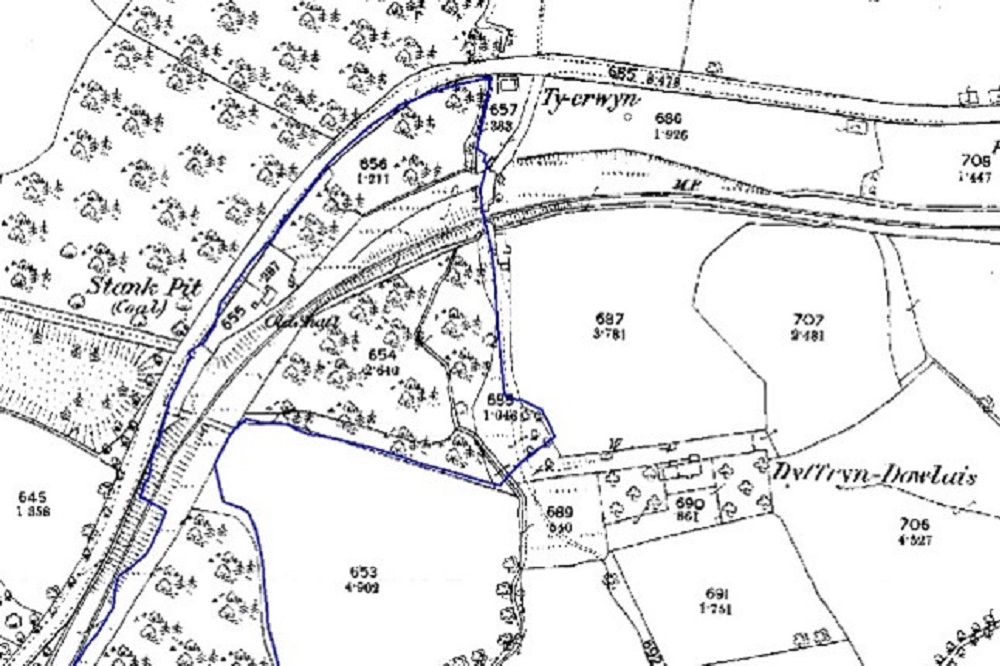

I went to the local parish council, made calls to Rhondda Cynon Taff council and was sent maps and facts from helpful people like Callum in planning, David in Acquisitions.

I’d not realised that in the woods there’d once been an old coal shaft and rail tracks which explained some of the walling and shadows of buildings (not an old witch’s house after all).

The woodland is now flanked by houses

The river is called Nant Ty Crwyn. As soon as I read this, I go again with wellies, stand in the river, say Hello, say Hello Nant Ty Crwyn, I’m glad to know you by name.

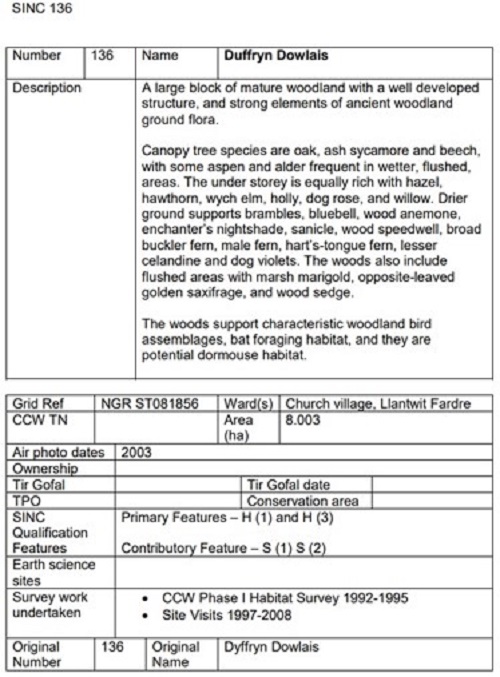

I find the name of the woodland from the document SINC 136: Coed Dyffryn Dowlais. SINC means that this is a Site of Importance for Nature Conservation; the description reads like a poem:

‘The under storey is equally rich with hazel, hawthorn, wych elm, holly, dog rose, and willow. Drier ground supports brambles, bluebell, wood anemone, enchanter’s nightshade, sanicle, wood speedwell, broad buckler fern, hart’s tongue fern, lesser celandine and dog violets.’

Last week, I located the ecologist who writes these records, Richard Wistow and phone him. Our chat is as rich as the woods. He explains what makes ancient forest; typically, it’s where an area has had tree cover since 1600, but more often it’s to do with the soil.

The soil in an ancient forest like this might have been there since the ice age. Brimming with life and communication, a complex ecosystem, underground network of life supporting fungi; harmony, it’s in the microbes, the pollens, the seeds.

I think of the burned out tree, and the fungi that are breaking it down, taking it back to the soil it came from.

As I’m sitting here writing to you from Coed Dyffryn Dowlais, the Nant Ty Crwyn turgid from rain-fall, the ash drips caught-rain from last night on me and the chubby robin dips his head to the side; I dip mine back.

You can find the entire series of ‘Letters from’ by following the links on this map

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

I absolutely love this . Thank you x

Ahh diolch Lottie 🙂

What a beautiful, well crafted letter. There is something for us all here, the letter nudges us, like ‘the river nudging us into the past, giving up messages of lives once lived’.

Thank you Thomas for your kind words