Letter from Cilfynydd

Molly Stubbs

The are very few places that best a beginning like the side of a valley, and very few valley sides better than Cilfynydd.

The cul-de-sac in which I grew up is the penultimate street in Cilfynydd, before the farmers’ land reclaims the mountain and all semblance of our small civilisation dissolves in a matter of a half-mile.

One hundred and sixty three metres above sea level, the air is thin yet easy, the smell of fresh cut lawns and a rare winter with no rain.

On a clear day like today, if you can fend off the ice in your joints long enough to scale a back-garden’s fence, you’ll be privy to the perfect view of the Taff Valley.

Right down to the bottom of the gorge and back up again, river blue, road grey, fields in blanket pearl with fresh snow, cars like pixels tearing silently across the picture, homes and churches puffing steam out of chimneys, clouds expanded with each breath of the trees.

Emerald and sapphire reach out to touch, blocked by the silver sliver of an extrusive fate.

Saturated clouds

“You won’t get any rising sea levels up here,” laughs Stanley Morgan, a resident of Cilfynydd since being birthed onto a carpet in Wood Street in 1943.

Though his 80 years since have seen him cross borders into Libya, Germany, and Belgium, though Stanley served as a royal driver for many years in the heart of London, it has all somehow led him back here.

To a small village he escaped at the age of 15, after deciding very quickly that the short life of a miner was not the life for he. In 1971, he watched the Post Office Tower crippled by an IRA bomb from a small and dusted window across the street, and now he watches as the postmen struggle to make it up Cil hill in the snow.

Ironically, despite Stanley having escaped his worries of rising sea levels, Cilfynydd is not immune to adverse weather. Rain seems to fall from saturated clouds here, the droplets fatter. Closer to the heavens, you see.

In 2009, after an amount of rain that seemed not unusual for the area, Cilfynydd’s drains burst and gallons upon gallons of rolling, frothing water went barrelling down Oakland’s Terrace.

One can imagine the hefty iron coverings popping off in time, like corks from crazed champagne bottles. Our new river ran straight down the street and directly into the post office.

My grandmother, an ex-army driver, navigated the geysers expertly, ferrying us all back to the house in one piece. Just as soon as we got into the house, back out the front door we went with wellies in hand, spending the afternoon splashing around the spectacle with the other children from the village.

Bluebells

Geographically, it is not only waterfalls of sewage seepage that the children of Cilfynydd have to entertain them. In the winters, you could swear the hills and divots were custom built for sledding.

Not five years ago, snow meant endless days off school sledding Egan’s gradual slope and trudging back up again. You could get all the way from Beecham’s Farm right down to Wood Street with nothing but a bit of laminated cardboard to carry you.

Now, the land over which I used to walk home from school among bluebells and brooks has been reclaimed by those very bluebells.

Secret paths

Assume the mind of your childhood self, sneak through the fence at the end of Egan’s, run along the back alleys and up the thousand steps, and you’ll come out at the Post Office. This little shop, wearing the same daisy and damson paint it has for decades, has bestowed the best ten pence mixtures onto every child in the village.

Across the street you’ll find dog poo alley. This is the pedestrian highway, so creatively named as it provides non-stop fun and thrills in the form of not-so-neatly-placed ‘obstacles’.

The entrance to dog poo alley, which at one time seems to have been a terraced house that was ripped from the street, connects to Cilfynydd’s ‘secret’ path network.

Whether it’s along next to the allotments, underneath the pylon and over the fence, or past the back of the minuscule miner’s gardens, every dark route, overshadowed with brambles and blackberries, will lead you to one of Cilfynydd’s three play parks.

Cil hill

As a child, I would sit on the roundabout in the lowest park that has since mysteriously disappeared. My attention would be captured, as I sat at the base of a mountain, by the neighbouring one.

Entirely less natural, the bare and barren expanse next to Cil hill reaches the same height, but it undulates in a foreboding roll that the eye is unable to tear away from. For this hill is made not from rock wrenched out of the earth by pure chance, but from colliery spoil, dug up by human hands and discarded here.

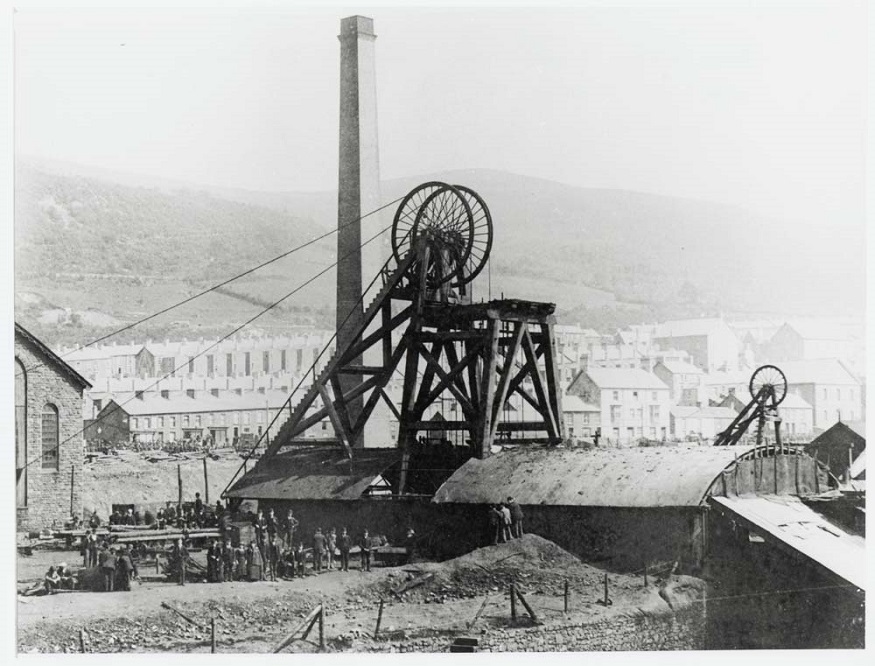

Long before it grew green, this charlatan would spit steam into the sky and, at night, glow like a volcano, blazes raging from within. That coal tip and the entire town once served the Albion colliery.

Underneath Pontypridd High School is 1,938 feet of shaft, and 3 miles of tunnels along the No.2 and No.3 Rhondda, and the Two Feet Nine, Four Feet, Six Feet, and Nine Feet seams stretching out to Graigwen and beyond.

No scars remain to tell of what happened, only a large concrete circle and a humble plaque, each breezed by in nonchalance every day.

Disaster

What the BBC called the ‘forgotten mining disaster’ occurred in 1894, 7 years after the first shafts of the Albion Colliery had been sunk. It is estimated that in those 7 years, 1000 tons of coal a day were raised from the depths.

For the week ending Saturday 23rd June, 9,542 tons of coal had been cut. Thirteen cage-loads of 20 men each were working in the mine that day. One who was at the lamp station reported seeing a blue flame tearing through the shaft. Firedamp, or methane to those of us fortunate enough never have had to work in a pit.

When it went up, so too did the coal dust. Two hundred and ninety men and boys lost their lives in two explosions, the luckiest of which were brought up by teams of rescuers in a hastily repaired cage to spend their final moments looking at the overcast sky, before succumbing to afterdamp and burns among thousands of spectators.

No doubt the Albion Steam Coal Company mourned the loss of the 123 pit ponies more than the men. They would be far more expensive to replace.

Coal

Cilfynydd was built to house those men and boys who dug and cut and pulled and counted coal, to feed and nourish their wives, their children who ran along the same alleys I did.

When the mine closed, so did Cilfynydd. The railway station was removed, the buses stopped running, the canal was paved over, the majority of shops on Richard Street disappeared. It’s possible to completely bypass Cilfynydd on the A470.

But there is something in me that, marvelling from the heights of this hill, believes people should come from across the world to stand where I stand, to look out at what I looked out at every day for 18 years.

God knows there are thousands of mountain climbers who would relish the steep stalk to the top of Cilfynydd that I dreaded to embark upon each and every day after school.

As it is, a Welsh town with 306 residents housing a disused colliery, three play parks, and a questionable (since closed down) pub is no tourist trap. I suppose we could do tours of dog poo alley, the next best equivalent to escape rooms.

Cilfynydd is a home. Its beauty, its unbecoming is reserved solely for us, the people who climb the mountainside because we must, because we always have done.

You can explore more Letters from around Wales and beyond here

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Wow. How beautifully written. How moving. It makes my heart ache.

Hugely entertaining article!