Looking for rare Welsh books in Los Angeles

Llewelyn Hopwood

Los Angeles is an unusual place to search for Welsh books and manuscripts. And yet, in the L.A. suburb of Pasadena, the beautifully manicured gardens and pristine Mediterranean-style buildings of the Huntington Library house one of North America’s largest collections of rare books and manuscripts from Britain.

Even so, nobody had scoured this collection for Welsh items. Therefore, when I was granted a Short-Term Fellowship at the Library, I began creating its first catalogue of items with a direct connection to Wales and the Welsh language, finding some thirty books and manuscripts, all dating from the early modern period (1547–1731).

Most of the print items have copies elsewhere, but copies of early books were never produced in large numbers, and few have survived. Therefore, each copy is precious and can be unique due to the handwritten notes left by readers.

The first remarkable example is a copy of Siôn Dafydd Rhys’s handbook to Welsh grammar – the first to be written in Latin – in which three readers from the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries have left their mark.

Some drew fingers pointing to their favourite passages, some corrected spelling mistakes, and printing errors, and some corrected and expanded the examples of poetry Siôn used to explain certain metres or concepts.

All early Welsh grammatical texts were more concerned with explaining Welsh poetry than with the Welsh language itself, but Siôn admitted that he didn’t know much about poetry: one later reader certainly agreed!

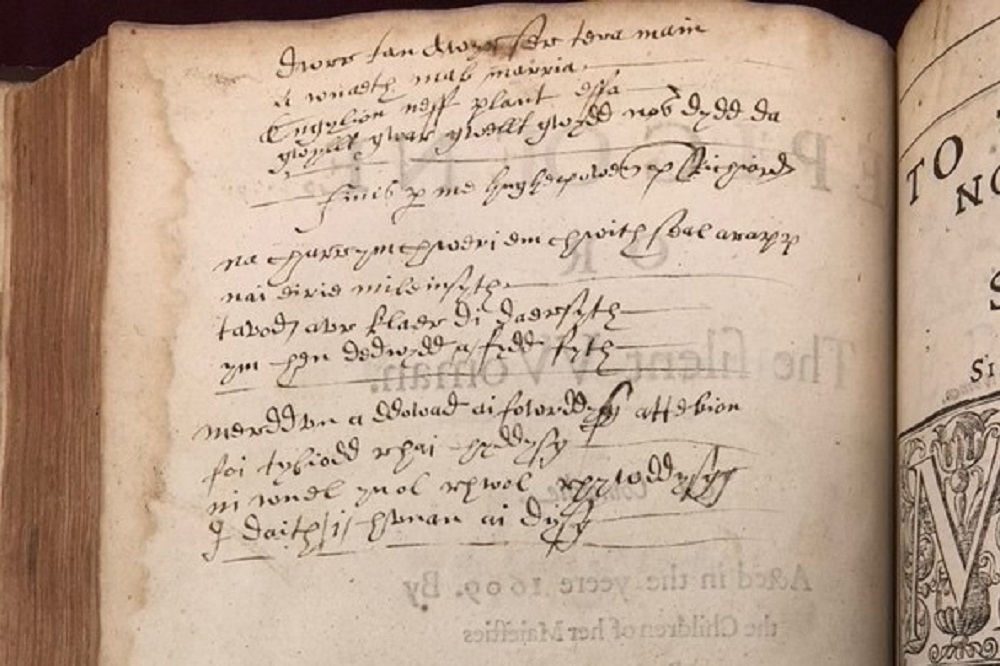

Another example is The Workes of Ben Johnson (1616). While the English playwright has little to do with Wales, in this copy we find three short Welsh poems (in the englyn form) concerning astrology and the poet-wizard Merlin as well the names of two Welsh readers: ‘Hughe ap Owen ap Richiard’ and ‘Ellen/Elin Owen’, probably of the Brogyntyn estate, where the copy was once held.

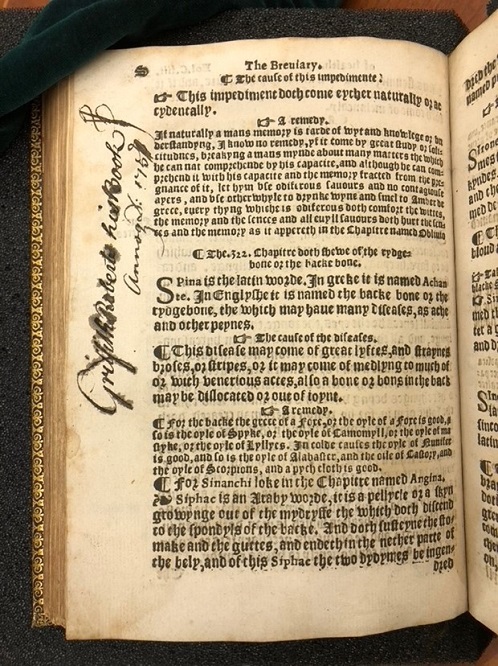

In a copy of Andrew Boorde’s Breuiary of healthe (1542), the name ‘Gruffydd Roberts’ is strewn over the pages in bombastic calligraphy, as if stating his rightful claim over the copy of this medical book, even though he gave it mixed reviews: ‘Mae llawer pêth yn ei le yn y llyfr ymma’ (There is many a thing in its place in this book) on one page, but ‘Hên, hên diddefnŷdd. ydyw y Llyfr hwn’ (This is a useless old book) on another.

(Coincidentally, one of many other texts by Andrew Boorde housed at the Huntington is his Fyrst boke of the Introduction of knowledge, containing stereotyped descriptions of Welshmen, complete with mimicked Welsh dialogue.)

Sixteenth-century polymath, William Salesbury, is also well represented. His Welsh-English dictionary, pronunciation guide to Welsh, and translation of the Book of Common Prayer – the somewhat rarer 1634 edition – can each be found.

Salesbury was also responsible for translating the New Testament into Welsh, and the Huntington’s copy is replete with evidence of previous Welsh owners and readers.

Inside its rich, wine-red covers, we find: the marks of contemporary readers correcting printing errors; a short Welsh poem (in the awdl form) attributed to sixteenth-century poet Tudur Aled; and three letters between twentieth-century poet Lewis Morris (of my home village of Llangynnwr) and rare books dealer Bernard Quaritch.

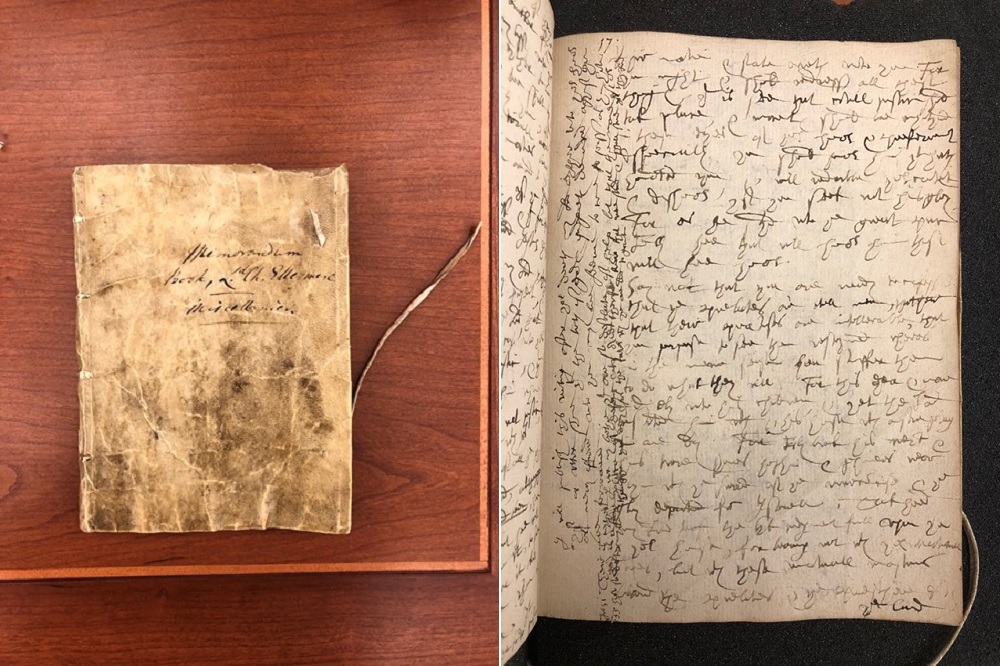

The only truly unique text is the manuscript known as The Notebook of John Penry. Penry (1563–93) was an early Puritan martyr whose advocacy for Welsh-language preaching and criticism of the Anglican establishment led to his arrest and execution.

Alongside the handwritten trial records and copies of his fiery pamphlets is a small, personal notebook written by Penry himself as he fled the authorities.

The very first lines read ‘Jesu Grist dechreu a diwed’ (Jesus Christ, from start to finish), but otherwise its biblical passages, drafts of letters to potential rescuers, and passages mentioning his wife and daughters back home in Wales are in English and Latin.

By their nature, manuscripts are unique, but here, this is compounded by: the presence of original covers and binding (a rarity); the inclusion of personal thoughts and feelings (relatively rare for the time, especially for Welsh authors); and the strikingly cluttered appearance, with Penry writing in all directions and on all corners of the page in the infamously messy handwriting style known as ‘secretary hand’, perhaps reflecting his desperate state of mind during his final months.

Beyond these, the collection contains clean copies of printed texts that have near-identical copies elsewhere.

But from Humphrey Llwyd’s map of Wales to John Prise’s defence of ‘British history’, these items are nonetheless influential, important, and rare, not least due to their very presence in a far-flung library that otherwise focuses on Californian history and botanical studies.

So, how did they get there? Beyond some recent conscious procurements, the primary answer is ‘by accident’.

Most Welsh items are part of the ‘Ellesmere Collection’: a collection built up over six generations of the Egerton Family – who took their name from, Thomas Egerton, 1st Baron of Ellesmere (1540–1617) – who were ardent collectors of all sorts of manuscripts and early printed books.

Given that most early Welsh books were printed in London and that some concerned English matters and language, many found their way into their Collection over time. (The John Penry items have a more direct connection since Thomas Egerton was the General Attorney during Penry’s execution trial.)

Then, in 1917, the entire Collection was purchased by Henry E. Huntington.

In the same way Henry purchased and merged businesses that were already substantial as he made his fortune through the railroads, when he started building his Library in the early twentieth century, he likewise purchased and merged collections that were already substantial.

Without knowing exactly what the thousands of items in each collection were, it was easy, then, for an ‘obscure’ Welsh text to slip through unnoticed.

It seems, then, that long before actors and footballers began travelling between Hollywood and Wales, books had been making the same strange journey.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Most interesting article!

Diddorol, Llew. Diolch am rannu.