Major Kurdish art exhibition brought to Wales to celebrate link between two nations

Martin Shipton

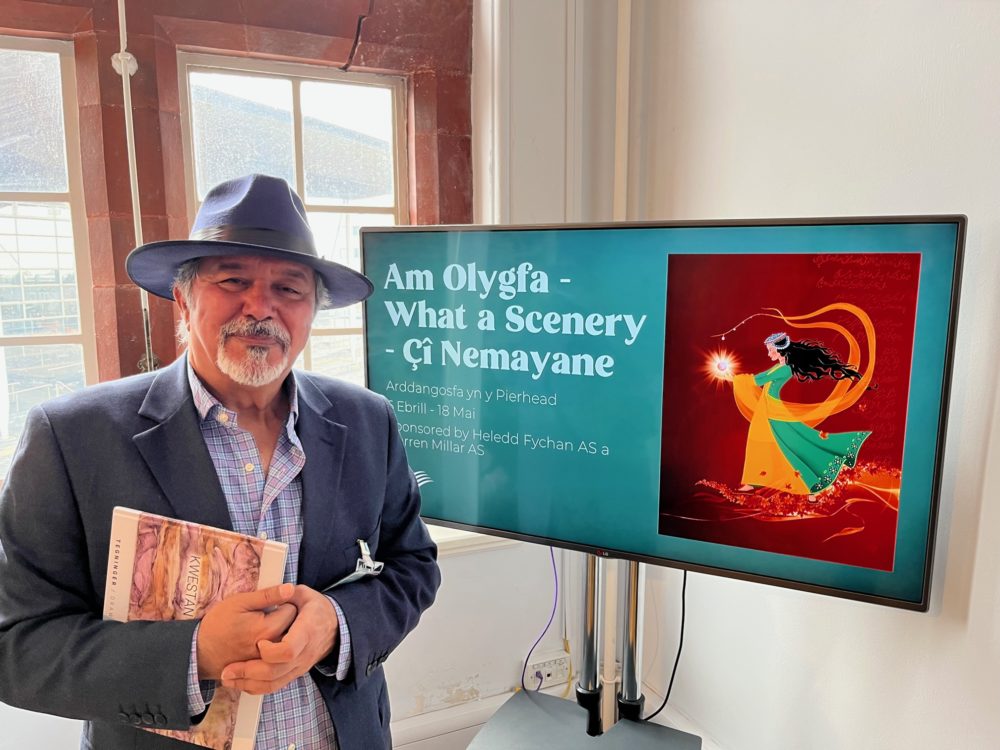

A major exhibition of Kurdish visual art has opened in the Futures Gallery at the Senedd’s Pierhead Building in Cardiff Bay.

One unusual feature is that the art works, by 20 prominent painters and sculptors, have been inspired by the poems of Abdullah Goran, seen by many as the foremost Kurdish poet of the 20th Century, whose poems have been translated into English and Welsh by Ifor ap Glyn, the National Poet of Wales and Aneirin Karadog, the Welsh-Breton writer.

The exhibition has been sited in Wales thanks to the efforts of Salah Baba Rasool, director of the Kurdish All Wales Association and the project director Alan Deelan.

The artworks on display are varied, reflecting both the Kurdish artistic tradition that, unlike traditional Islamic art, permits the representation of the human form and the luscious landscapes of Kurdistan, an ancient but stateless nation that has population centres in Turkey, Iraq, Iran and Syria.

There is a significant Kurdish community in Wales, and especially in Cardiff. Ann Clwyd, the late Labour MP for Cynon Valley who died last year, was a great champion of their cause.

Parallel history

Asked about the link between Kurdistan and Wales, Mr Deelan said: “The Kurdish nation and the Welsh nation. I find that there’s a parallel history and shared objectives. The struggle is to preserve a culture and a language, and that’s exactly what ties us together. This is what brought my family to Wales in the 1980s.

“It’s very clear from the project that it was designed particularly with this in mind. It was my choice to bring it to Wales because of this very reason. We are celebrating this shared history. It is a sad history, but it is a shared history nevertheless. We’ve managed to some extent, and Wales perhaps more so, to achieve what we want to achieve.”

Mr Deelan pointed out that in Turkey, even in areas that have a very high proportion of Kurds, the teaching of the Kurdish language is forbidden in schools. It reminds him of the “Welsh Not”, when Welsh-speaking children were forbidden on pain of being beaten to speak Welsh at school.

He said: “That’s exactly what is happening now in Turkey. Turkey is tooth and nail when it comes to fighting any elements of Kurdish culture – any manifestation of it. So suppressing the Kurdish language is of course very important to them because allowing it would detract from the hegemony of their culture, and veer children away from wanting to become what Turkey wants of them. Every moving thing in that land has to be Turkish.

“A great Kurdish writer called Musa Anter used to say: ‘If me speaking my language makes you angry, I am sure you’re in the wrong land’. He was assassinated by the Turks in 1992.

“Turkey didn’t exist 800 years ago. We were there before anyone else. And that is the region we live in today, from the dawn of humanity if you will.”

Speaking of the divergent styles between traditional Islamic art and Kurdish art, Mr Deelan said: “The art scene across Kurdistan (North Kurdistan – Anatolia, West Kurdistan – Syria, South & Central Kurdistan – Iraq, and East Kurdistan – Iran) has not been influenced by art from the Islamic era.

“Additionally, Kurdish visual artists focus on consolidating Kurdish identity, highlighting the natural beauty of their homeland, and addressing contemporary issues such as life’s struggles, womanhood, the emancipation of women, and celebrating the ethnosymbolisms of the Kurdish nation.”

He then pointed to a poster, painted by the artist Snobar Avani advertising the exhibition on display in the gallery, saying: “This lady is holding droplets and they are pearls. She is so eager to show you the pearls. You can appreciate the beauty of it, but at the same time she is holding on dearly to it because she wants to preserve it.

“So the culture that we want to keep we want to hold to ourselves. Islamic culture is not the identity – or the primary part – of the Kurds. It’s a religion. It’s Kurdish culture that forms the unique identity of the Kurds, not a religion. So unless someone is unusually highly religious, there isn’t any representation of religious themes in Kurdish art.

Art for Kurds is a means to represent their ethnicity with the help of the very vivacious colours of nature seen in Kurdistan. It allows Kurds to celebrate their homeland which, although they live in it, remains elusive.”

The exhibition in the Futures Gallery at the Senedd’s Pierhead Building runs until May 18.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.