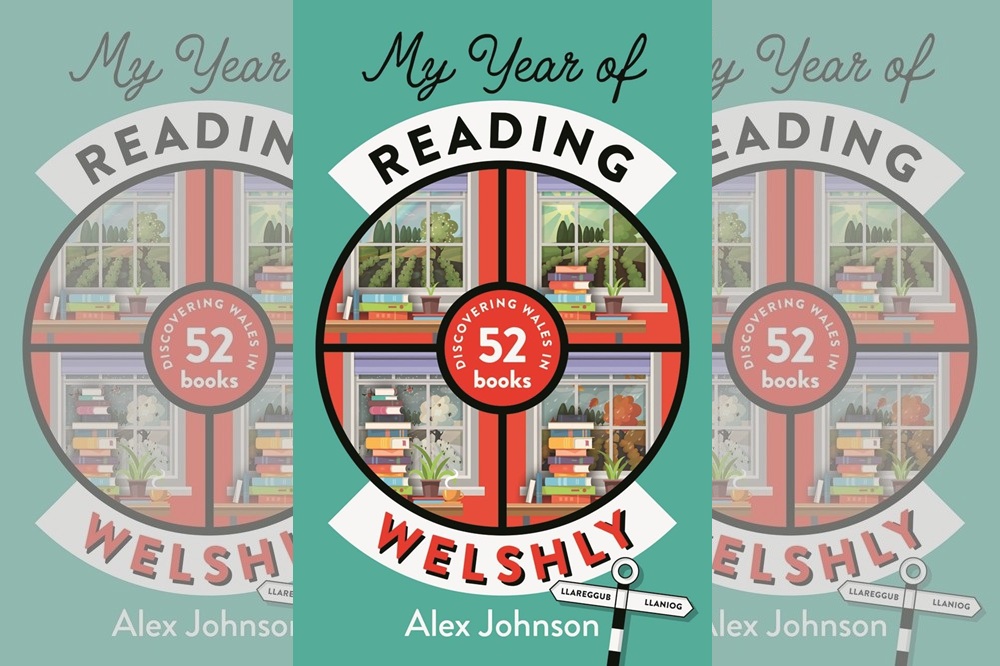

My Year of Reading Welshly: Discovering Wales in 52 books by Alex Johnson

Desmond Clifford

The title is admirably clear. The author, Alex Johnson, is not Welsh and lives in St Albans. He has no strong connection with Wales but feels interest and thought it would be fun to read for a year according to a plan and chose Wales as his theme.

Reading lists are a fun genre and I’m uncritically in favour of books which drive readers to works by Welsh authors.

Sensibly, Johnson adopted some guidelines. He limits himself to the last hundred years. The books must be available in English but can include translations from Welsh. He includes fiction, travel and poetry – a rich seam but, because he excludes history, there’s no John Davies, RR Davies, Geraint Jenkins, Kenneth O Morgan, Dai Smith or Gwyn A Williams. It’s reasonable to draw a line somewhere but a shame, all the same; historians have produced some of the best books of recent times.

The author in no way suggests these are the best 52 Welsh books from the period. It’s a selection, relying on recommendations and his own research.

Ragbag

What we end up with is a ragbag, and nothing wrong with that. As the author says, “Reading should be a pleasure, not a to-do list.”

There are broadly two responses to books in this list-genre. One is “discovery”, finding new authors and/or new works to try.

The other is to assess the chosen list against your own sensibilities (the posh word for prejudices).

Let’s kick off with poetry. The period is dominated by the Thomases, Dylan and R.S. I agree with Johnson that Under Milk Wood (1954) comes alive in performance but lies flat on the page; best head for an audio version.

He selects Song at the Year’s Turning (1955) as R.S Thomas’ offering: magnificent. Fun fact; I’d forgotten that R.S was nominated for the Nobel Prize in 1996 and initially declined the nomination. It’s a pity he didn’t win for several reasons; chiefly because he merited it amply and, secondly, he could have vied with Bob Dylan for the least gracious acceptance (Bob declined to attend the ceremony and sent Patti Smith to sing Hard Rain).

If I’m allowed just one moment of snootiness, I was a little surprised the author, who is a professional bibliophile, said he’d not previously heard of David Jones. Jones’ reputation has steadily risen and his artwork and first editions sell for fortunes; he’s among the more fashionable Welsh writers these days.

At any rate, Johnson gives a good account of the difficult(ish) In Parenthesis (1937). Alun Lewis, Lynette Roberts, Brenda Chamberlin, Gillian Clarke and Menna Elfin are all also covered positively.

Imbalance

My slight complaint about the poetry offering is imbalance. If I’d been among the author’s mates at the snooker hall (apparently that’s where he discusses literature) I’d have recommended Idris Davies for a strong sense of time and place, Harri Webb for an explicitly nationalist voice and devilment, and Rowan Williams for contemplation.

There are also decent anthologies of collected modern verse, both English and translations from Welsh, which would have given him a broad overview.

Farming features heavily in the list, and fair enough given its huge part in the Welsh experience.

There’s a substantial literature of people moving to rural Wales to follow a farming dream only to discover – shock, who knew?! – that farming is hard and no road to riches. Thomas Firbank, Horatio Clare, Cynan Jones, Bruce Chatwin: marriages fail, families fall apart, lives atrophy, badgers are brutalised, and life is tough.

The slate quarry experience is represented by Kate Roberts’ The Awakening (Y Byw Sy’n Cysgu). One Moonlit Night (Un Nos Ola Leuad) by Caradog Prichard makes the list.

Johnson notes that some see Prichard’s novel as the best ever written in Wales; a good debate for the campfire after a day at the Eisteddfod, and certainly a worthy candidate. Manon Steffan Ros’ excellent and contemporary The Blue Book of Nebo ensures that north Wales is well represented.

Ynys Enlli, one of Wales’ smallest geographies, gets two books: one from Brenda Chamberlin and another from the contemporary Fflur Dafydd, Twenty Thousand Saints.

Linguistic apartheid

The way the author un-self-consciously mixes translated Welsh and English language texts is one of the things I like most about this volume; I’ve always disliked linguistic apartheid in Welsh literature. (Two books from Ynys Enlli puts me in mind of the now bittersweet joke about the British Lions selection some years back: “…the Scots are unhappy because there’s only one man in the squad from Scotland; the Welsh are unhappy because there’s only two from Banc-y-Felin…”).

North and rural Wales are generously represented. “How Green Was My Valley” by Richard Llewelyn largely carries the torch for the Valleys’ industrial experience. I agree with Johnson that Llewelyn’s book is ambiguous. It doesn’t work well enough to be considered a classic but, all the same, the novel displays imaginative power and a sense of place and time; it’s too easily dismissed as a stereotype. (Another fun fact: How Green Was My Valley scooped the best film Oscar in 1942 beating Citizen Kane, which some now think is the best film ever).

Fresh Apples by Rachel Trezise shows a more up to date view of Valleys life.

Several “classics” find their way onto Johnson’s list. Emyr Humphreys is represented by his short work A Toy Epic, a coming-of-age story of mid-century Wales and sociologically interesting.

Limitations

Raymond Williams, around whom there is something of a cult, is represented twice, by The Volunteers and Border Country. I share Johnson’s sense of the Great Man’s limitations as a storyteller; like medicine, Williams may be good for you even if not necessarily enjoyable.

In the absence of Welsh sources or well-informed friends, Johnson has done well in piecing together a selection. Three authors are included twice: nothing wrong there but he could have broadened the selection further had he limited himself to a single representative work from each author.

There’re lots of reasons to be interested in The Gododdin but, in isolation, it’s a list of men (very sensibly) getting drunk before facing gruesome battle and near-certain death.

Its inclusion here feels a little too random, especially since the translator, the excellent Gillian Clarke, is better represented by her original verse in The Sundial.

I completely agree with Johnson’s judgement on Kingsley Amis’s The Old Devils: “It’s terrible.” It’s the worst book ever to win the Booker Prize (1986) and sits like a grubby stain on the roll-of-honour. Mean-spirited, puerile, unfunny.

One of the judges that year was Bernice Rubens, herself one of Wales’ finest novelists, and the only Welsh Booker winner. Johnson selects her 1983 historical work, Brothers. I think it’s a much better book than Johnson does and, if he’s only picking one, it’s a shame he chose this.

The long historical novel was an exception for Rubens and, as an introduction, Johnson might have enjoyed one of her sharper, more representative novels like I Sent A Letter to my Love (1975) or Yesterday in Back Lane (1995); she wrote 25 novels so plenty to choose from.

All in, this book achieves what it sets out to do. It lists books connected to Wales and offers ratings on their readability. It’s designed to be fun, and it is.

Respectful

There’s a question about its intended audience. The author is respectful of Wales without being cringey, sympathetic on identity issues and doesn’t pretend expertise.

Welsh readers, however, will mostly have a different starting point to the author, so perhaps this book would be most impactful for non-Welsh readers.

That said, if taken in the spirit offered, there are interesting titles explored and only a few (M. Wynn Thomas?!) will have read them all. I’ve noted several I’d like to explore on this recommendation: Menna Gallie, Ron Berry and Alys Conran, for example.

There’s a long list of absences: Jan Morris (travel is allowed), Nigel Jenkins, Caradoc Evans, Rhys Davies, Saunders Lewis, Islwyn Ffowc Elis, Angharad Price, Alexander Cordell among others.

In a way the absences are a healthy indicator of the volume and variety of Welsh writers across this period, and there are many more worthy of exploration.

Arguably, this book is a little unbalanced and a refined list might offer a fuller foundation in Welsh literature, but this, perhaps, is to miss the point.

The book is fun and aims to get people reading beyond the display table of the bookshop, which can only be a good thing.

My Year of Reading Welshly is published by Calon and is available here and at all good bookshops

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.