Nigel Jenkins introduced

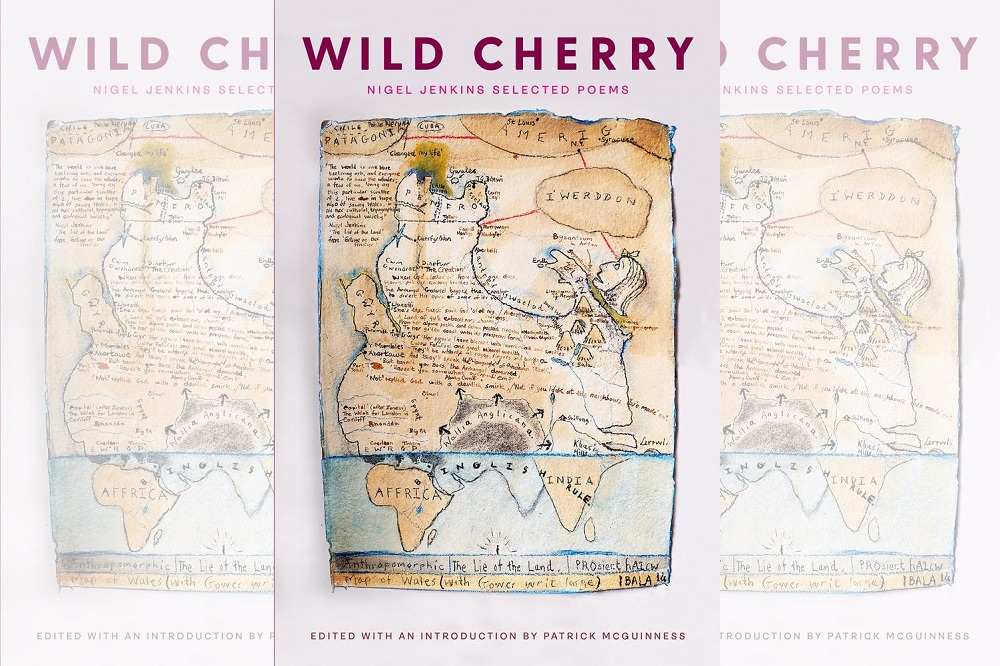

The poet Nigel Jenkins’ selected poetry was recently published by Parthian in a volume called Wild Cherry. We are pleased to publish the introduction to the book by its editor.

Ambushed by Words

Patrick McGuinness

When Nigel Jenkins died at the age of sixty-four in 2014, he left behind a body of work remarkable not just for the range of its forms and occasions, but for the variety of its literary, cultural and political commitments.

The author of a groundbreaking book of travel-writing about the Welsh Calvinistic Mission in Khasi, North-East India, Gwalia in Khasia, which won the Wales Book of the Year in 1996, Jenkins wrote two books of … what exactly – topography? history? psychogeography? – about the city he loved but never idealised: Real Swansea and Real Swansea Two.

Published posthumously in the same series, and with the same breadth of knowledge, snappiness of phrasing and freshness of perspective, was Real Gower (2014), on which he had published, with the artist and photographer David Pearl, a richly-illustrated book in 2009.

Deep research

All three books also contain poems in and among the prose, as if to remind us that, for Jenkins, poetry and prose, far from being opposites, beget and sustain each other. These books are characterised by deep research, but also an understanding of how places and their histories are experienced in the here and now.

This is reflected in the poetry Jenkins produced for public spaces in Swansea and elsewhere, where his words, executed in stone, steel, glass, and neon, adorn buildings and monuments, always arrestingly and without any trace of municipal committee-pleasing.

His critical guide to the Welsh poet John Tripp appeared from the University of Wales Press in 1989, and a selection of essays on literature, place and culture, was published in 2001 as Footsore on the Frontier.

The author of numerous books and pamphlets and the editor of several anthologies, Jenkins was also one of the editors, with John Davies, Menna Baines and Peredur Lynch, of the Encyclopaedia of Wales/Gwyddoniadur Cymru, which appeared in 2009.

Attentiveness

I mention Jenkins’s non-poetic writing in order to establish, from the start, the way his work centres itself in relation not just to Wales, its languages and its cultures, but to the world at large.

Jenkins had a clear understanding of what it meant to be a Welsh poet writing in English in the 20th and 21st centuries. That understanding was informed and energised by its attentiveness to Welsh-language culture, and from its sense that the English-language tradition of Wales could learn from the centrality of poetry in Welsh-speaking society.

Jenkins saw himself in the tradition of what he called, quoting Harri Webb, ‘the poet as essentially a social rather than a solitary character’. And yet that is only one facet of his work, because Jenkins’s poetry is also intimate and reflective, and though there are moments of solitude, there is never a retreat into private language.

‘As we reappropriate some of the active principles of our native tradition, we need at the same time to be open to and avid of non-Welsh stimulation. More poetry from Asia, the Americas, Africa…’, he argued in a talk given at the opening of Tŷ Llên in Swansea (now the Dylan Thomas Centre) in 1995.

On the same occasion, he made the case for poetry’s role in this ‘reappropriation’: ‘Poetry should be out and about, doing a job in the world, ambushing people, not hiding in classroom cupboards and magazines that nobody reads’.

Not for nothing did Jenkins title his 1998 volume Ambush: a one-word poetic manifesto, it was also a fitting description of the way in which his own poetry stakes its claim upon us.

Grounding

In an interview with the magazine Roundyhouse in 2006, Jenkins described how, after a wounding review of his first poems, he returned to the family farm in Gower and started again.

The poems in which, by his own estimation, he began to sound like himself are the ones that open this book. ‘Pig-Killing Day’, ‘First Calving’ and ‘Castration’ are visceral poems about the realities of farming life, conveyed in what Jenkins called ‘the plain, ungarnished language’ which he developed as a counterweight to the excesses of ‘the Dylan Thomas imitation epoch’.

The return to Gower was a grounding, or a re-grounding, and it was literal as well as metaphorical.

Jenkins’s poetry is often concerned with grounding, but it is also a poetry of connection and connectiveness. For Jenkins, poetry must do more than merely express the romantic self or the atomised postmodern ‘I’.

He dismissed ‘the poetry of demure ego, whimsical anecdote, genteel suburban regret and detail-obsessed imagism’, and, like the poets he knew and admired in Welsh and English, Jenkins wrote with Wales in mind.

The Wales he wrote from, and wrote towards, was not some abstract idea, but a living place, imperfect and contradictory and beset with divisions, while also offering fertile grounds for hope. Describing a walk along Offa’s Dyke in Footsore on the Frontier, Jenkins writes:

Borders, frontiers, shadow lines of one kind or another are a familiar and sometimes painful condition of Welsh life. But a walk down the Dyke concentrates the mind on what has made us one, a nation, in spite of our notorious internal dissensions.

Polemical

Jenkins campaigned for Welsh devolution and international solidarity with the same sense of purpose as he campaigned against nuclear power, militarism and racism.

A politically- and culturally-committed poet – engagé, would have been the word, had he been a French writer – he was unafraid to be satirical, or epic, or polemical, or to be simply and frankly angry. Auden’s (already ironic) line ‘Poetry makes nothing happen’ did not convince Jenkins, because poetry for him is the happening.

Words and actions were not opposites, they were complementary: faced with a choice between doing something for a cause and writing a poem about it, Jenkins chose both. A spell in prison for protesting against the presence of American bombers on Welsh soil, and the frequent opprobrium of reactionaries and political time-servers in letters pages of the newspapers (which he relished), attest to that.

‘An Execrably Tasteless Farewell to Viscount No’, his send-off for George Thomas, the anti-Welsh, anti-devolution and anti-European Labour Lord and long-time speaker of the House of Commons, ensured poetry made the front pages of the London newspapers.

Savage and witty, the poem channels anger into craft, reminding us that poetry has often been a thorn in the side of authority. ‘Poets are particularly dangerous enemies’, reflected The Observer at the time.

*

Acts of Union, subtitled Selected Poems 1974-1989, appeared in 1990. The title alludes to the acts of union by which Wales was annexed to England, but the book’s original cover – a naked couple intimately entwined – suggests that other kinds of acts of union are also part of poetry’s purview.

The political and the personal are never far apart. This Selected Poems takes its cue from Jenkins by starting from Acts of Union, and is presented chronologically, up to and including a selection from his last book of poems, O for a gun (2007).

Undimmed

Once I had made my selection, I was struck by how the book begins with a handful of poems set on the Gower farm and ends with a series of haiku, and a sequence entitled ‘Advice to a Young Poet’. The ‘young poet’ in question may be any one of the hundreds of students in creative writing Nigel Jenkins taught and mentored across his career, first at Trinity College Carmarthen, and then at the University of Swansea.

The ‘young poet’ may also be his younger self, addressed across the decades, with an energy undimmed by experience. As for the haiku, of which Jenkins produced two volumes, we may think of these as three-line portholes onto other cultures and eras, and into other ways of apprehending the world.

A comment in Blue, his first book of haiku (published in 2002), gives us a telling insight into the connectiveness of Jenkins’s vision:

An early expression, in Welsh art, of the spirit of haiku, it seems to me, comes not in words but in paint: Thomas Jones, Pencerrig […] may not have heard of haiku, but his exquisite little study (16cm by 11cm) of ‘A Wall in Naples’, so at odds with the picturesque floridities of his time, pays revolutionary and haiku-like attention to the numinous life of ‘nothing more than’ a battered old wall and some rags of washing hung out to dry.

Great small canvas

Jenkins compares the haiku with the englyn, forging a Welsh link with a Japanese form, and with his own ‘Cosmic Gnomes’ (included here), based on the ancient Celtic inscriptions known as Ogham Stones.

Then, in an inspired observation on the way artistic affinity works across cultures, he brings in Thomas Jones’s great small canvas, reminding us that – before it is poetry, before it is painting, before it is music – art is a way of seeing and feeling that enlarges experience.

Jenkins’s work is about these connections, these affinities and enlargements: Wales and the world, the visual and the verbal, the individual and the community, the present and the past.

Merciless satires

This book contains love poems and poems of desire, lyric poems and public poems for public spaces, occasional poems that transcend their occasions, merciless satires, and poems that borrow epic voices, whether of bravado or lament, and retool them for today’s challenges.

There are poems written in the spirit of high-intellectual play and urgent poems about environmental degradation, militarism, nuclear folly, imperialism and capitalism. There is beauty and precision, outrage and indignation, savage wit and deep empathy.

What Jenkins’s poetry entirely lacks is hopelessness, and where there is cynicism, it is reserved for those who deserve it: philistines, defeatists and political cronies.

The book also contains a number of Jenkins’s translations from the Welsh – a reflection of his commitment to the bilingualism and biculturalism of his country, and to the idea of a community of poets.

A sense of history underpins Nigel Jenkins’s writing, but it is the present that propels it. In that sense, his poetry and prose are part of a single, albeit various, oeuvre. They are the work of a writer who believed that poetry has a duty to engage with the world as it is, while holding out the imaginative possibilities of what it can be.

Wild Cherry: Selected Poems by Nigel Jenkins, edited by Patrick McGuinness, is a Books Council of Wales Book of the Month selection for December. It is published by Parthian and is available from all good bookshops.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.