‘No heroics, boys!’ Friends and collaborators pay tribute to Mike Pearson

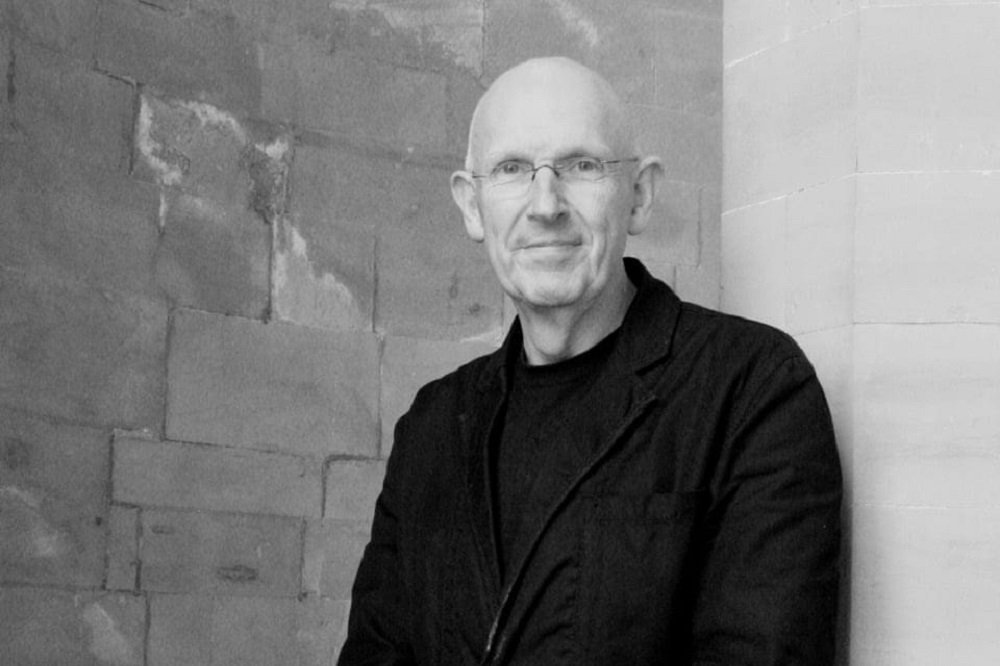

Tributes have been paid to Mike Pearson, one of the most influential figures in Welsh theatre in the past half century, who passed away last week.

As a groundbreaking theatre practitioner and academic Mike Pearson had a long and remarkable career which began at RAT Theatre and Transitions Trust community arts project in 1971, after initially training as an archaeologist at University College Cardiff.

Later he became co-director of Cardiff Laboratory Theatre alongside Lis Hughes Jones, with whom he founded the Brith Gof Theatre Company in 1981.

Between 1997 and 2014, he became first a lecturer and then professor of performance studies at Aberystwyth University, where his wife Heike Roms also taught.

The range and compass of contributions gathered below from collaborators, fellow directors, actors, composers and teachers reflect the range, integrity, curiosity and unflagging energy of a supremely gifted theatre maker, teacher, academic and all-round inspiration.

Gilly Adams

In the fullness of time I, like many others, will be able to write about the legacy of Mike’s seminal theatre work (Cardiff Laboratory Theatre; Brith Gof: Pearson/Brookes) and his influence on generations of young students at Aberystwyth University as Professor of Performance Studies there.

Tributes to his more than fifty years of achievement are flooding in from European theatre makers, academics, colleagues and friends and there are surely books to be written about this modest man, who did so much and was still fully engaged with his different projects to within a few days of his death.

But, in the shock and sadness of Mike’s departure, I can only write about the man I have known since the 1970s when I arrived to work in the drama department of the Welsh Arts Council.

I was much in awe of Mike and it was difficult for us to negotiate our mutual reticence until the day he sat in my office, on the eve of a trip to Japan to study Noh Theatre and shared his extreme anxiety about the challenge of taking the appropriate presents for his teacher – given the complexity of Japanese protocols about such things.

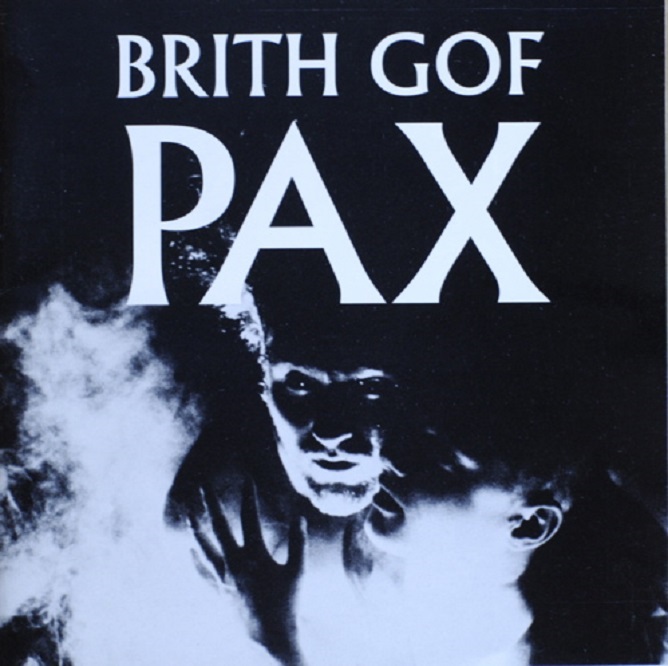

So, a tentative friendship was formed and Mike offered me some of the most memorable theatre experiences of my life – The Gododdin, Pax, Black and White, The Persians – and then the greatest gift – Good News from the Future.

In 2014 Mike conceived the idea of a physical theatre company for the over sixties, initially as a way of experimenting with techniques he had used in the seventies. Some free workshops followed and were so enjoyable that a nucleus of the participants clamoured for more and Good News from the Future emerged.

We have been meeting and working together on a regular basis ever since with occasional forays into the public eye with performances like What comes Next? and Museum Pieces given in arts centres, art galleries and museums.

Covid stopped us in our tracks for quite a while but eventually we became bold enough to re-convene and met almost every Sunday morning in Thompson’s Park in Cardiff prancing about under the trees in all seasons and all weathers.

Love and gratitude

My abiding image is of Mike standing, waiting under a particular beech tree, with his jacket buttoned up and his flat cap, turning to wave and smile a welcome.

Our intent was serious but we laughed so much, got confused on occasion as older people do, made mistakes, did wonderful and unexpected things, discovered we could do more than we had ever anticipated.

What can I say about Mike in that context?

Words bubble up like: generous, funny, rigorous, modest, affectionate, creative. He smiled so much, even when we were exasperating: he was always encouraging “that was great, I’d pay to see that” or “that bit was really good, let’s keep that”; and always offering suggestions and instructions in his gentle, unassuming way “maybe it would be better to…….”

Yesterday, in Chapter we performed A Walk in the Park, the piece he had been working on with us until two weeks ago.

We offered it to honour him: In grief, with love and gratitude for all he has given us, all that joy and laughter, creativity, friendship and purpose.

We will go on working together. How could we let him down?

Mike Brookes

It is difficult to know where and how to begin to articulate the loss of Mike. So much of what we shared was experienced and unspoken.

The consistent impact and continuing legacy of his decades of work in Wales are simply unparalleled.

His extraordinary care and understanding of the real world possibilities of physical performance made him such a profound inspiration for so many of the generations of performers that he taught and worked with.

Yet for many he was first and last a thoughtful and articulate friend. In my case that friendship, and the ways that it encouraged and challenged ideas, became a very rare and genuinely enabling collaboration.

The type of collaboration that I don’t expect to find again, and that allowed us to travel paths we would not have been able to navigate and map alone.

In the end, I guess we can each only really speak of our own loss.

Mike and I spent twenty years imagining the work as places and situations where we might want to meet and be, where other ways of sharing and being together might become possible.

We were lucky enough to be able to realise some of them.

It is in those yet to be imagined places and possibilities that I am going to miss him most.

Richard Gough

Mike was a pioneer, a change maker and innovator, he led the way for a distinctive form of Welsh theatre – experimental, physical, site-specific, environmental, and iconoclastic – that resonated on a global stage.

He was an ‘influencer’ in the old, pre social media sense, through contact and contamination, through people to people, through a tangible passing on of know-how, curiosity, and knowledge, through theory and practice.

For fifty years he sustained an extraordinary output of work that ranged from intimate one man shows, often autobiographical and revelatory, to large scale, site responsive, productions that were spectacular and awe inspiring, delving into the mythical dimensions of Wales, its industrial heritage, and its conflicted histories.

He was both performer and director in these productions and he was their most vehement critic, analysing their form and function, appraising them in the light of emergent critical theory and the optic of performance studies and elaborating his own insightful theories advanced through conference presentations, journal articles and books, that, like his theatre works, garnered an international following.

Space and place

One of Mike’s earliest solo pieces was The Lesson of Anatomy (1974) based on extensive research around the French visionary of theatre, Antonin Artaud.

The Lesson of Anatomy was an athletic, tortuous and mesmerising piece, Mike was to reconstruct and re-perform it exactly forty years later (to the day) in the same venue – the Arena of the Sherman Theatre, Cardiff.

In many ways I think Antonin Artaud guided Mike throughout the last fifty years through an intense exploration of the anatomy of theatre, and in part the realisation of Artaud’s search for a Theatre of Cruelty, a theatre that challenges audiences, all conventions and complacency within theatre, all orthodoxies and limitations and explored the very boundaries of performance.

Mike’s undergraduate degree in Archaeology (Cardiff 1968 – 1971) was to have a profound influence on him and enhanced his awareness of space and place, of past and present, of sight and site, of the material remains of human endeavour and a speculative imagining of what human toil might have taken place in those landscapes and ruins.

In many ways I think this formative training in archaeology led to a forensic analysis of the function of theatre, and an inquisitive approach to performance making.

His productions, whether solo or ensemble (and multi-dimensional) were often defined by a single organising principle, not mathematical or scientific but intuitive and visceral.

A central image or action, or juxtaposition to space/place, led to a unifying, persuasive and arresting dissonance that immersed the audience and enthralled.

Generous and aquisitive

Mike collaborated with many other practitioners and nurtured their individual and different artistic aspirations; in this sense he was both immensely generous and acquisitive.

He could be both mentor and sparring partner, he brought out the best of their emergent sensibilities and harnessed their skills for the creative realisation of the work in process.

He developed his own methods and strategies through these collaborations and enabled his collaborators to determine their own trajectories.

I was one of the earliest collaborators as part of Cardiff Laboratory Theatre between 1974 and !980, and Dave Baird had proceeded me.

Most notable others were Cliff McLucas, Richard Huw Morgan, John Rowley, Marc Rees, Mike Shanks, and Mike Brookes, who worked with Mike to realise ground-breaking work with Brith Gof, The National Theatre of Wales and Pearson/Brookes.

Partners and collaborators

Alongside these merry men were three women at different stages of Mike’s life who made significant impact on his work, all were lovers, muses, and unfailing companions: Siân Thomas in the 1970s, Lis Hughes Jones in the 1980s and for the last thirty-three years Heike Roms (for whom my heart aches).

Siân brought to Mike’s attention the power of the virtuosic female performer, a trembling fragility with diamond-like presence, offsetting his masculine and macho persona that had been inculcated through RAT theatre (1970 – 71) and their performances of physical risk.

Lis awakened Mike’s perception of Wales and the Welsh language, of the folk and mythic resonances in the landscape and most of all the potential for theatre to contribute to the imaginings of a nation and to nation building.

Heike deepened Mike’s theoretical explorations and nurtured and supported his increasing presence within international circles of academic discourse and debate (in addition to being a life partner, soul companion and resolute defender).

These are but glib generalisations, but I think it is important in paying tribute to the remarkable achievement of an individual to acknowledge the formative role partners and collaborators play.

It is also a way of marking Mike’s endearing quality to be open, and be influenced by, those people he encountered, worked with, and lived with.

Integrity and humanity

Mike was an inspiring teacher, public speaker, author, and conference presenter. I attended his regular weekly workshops at Llanover Hall in Cardiff (1973-75), a sort of experimental theatre club, a gang of 17- and 18-year-olds exploring the latest theatre exercises and devising strategies garnered from New York’s Living Theatre (Beck and Malina) and Open Theatre (Chaikin) and Poland’s Laboratory Theatre (Grotowski).

It changed the course of my life, and I became a devotee of experimental theatre, jettisoning all my interest in university or a professional career and joining Mike in developing Cardiff Laboratory Theatre.

For several decades I invited Mike to run sessions at the Centre for Performance Research (CPR) Summer Schools and extended week-long workshops as a part of other programmes, I witnessed the impact he made on young practitioners; they were inspired by the interlacing of theory and practice, the depth of know-how of an experienced artist-scholar and the wide interdisciplinary references and contemporary issues that Mike brought to the table.

This approach to teaching was advanced by Mike when he took up a full-time position at Aberystwyth University (1997) and pioneered Performance Studies as an undergraduate degree before this audacious shift Performance Studies was only adopted as a post graduate programme at various institutions around the world.

Mike Interlaced practice and theory and foregrounded theory based upon practical experiment and discovery, nurturing an articulate practitioner.

I invited Mike to present at numerous conferences curated by CPR and witnessed his presentations at many other major international gatherings.

He astonished his audiences by transforming the usual dry academic paper into a virtuosic performance-lecture, the scientific/academic merit of the presentation was never compromised but the delivery was embodied in a physical presence that was immediately captivating, often extending the thesis of the argument through a material manifestation.

In this regard he was one of a handful of artist-scholars globally who could make academic presentations enthralling and engaging – to profess without scholarly and over citational grandstanding.

A Professor of true integrity and humility.

A soul alight

Mike’s theatre productions often had a dark foreboding quality to them, disturbing, visceral, and sometimes violent, it always surprised me to recall that he was a keen ornithologist, as if in my mind birdwatching presupposed an idyllic pastoral and peaceful orientation.

In our walks in the hills surrounding Cardiff in the mid-seventies Mike tried to awaken ‘birding’ within me, but I was nineteen, besotted with Patti Smith (and her Horses) and drawn more to the detritus of urban decay.

Now, I would like to think of Mike, freed of body and material constraints, flying amongst the birds, a soul alight, with him initiating new flight paths, trajectories and spectacular ariel displays; shape shifting as he did in life, at one moment the reclusive Wren, the next the inquisitive Jackdaw and then the magnificent Red Kite soaring over Wales.

No bird soars too high if he soars with his own wings.

(William Blake)

Jon Gower

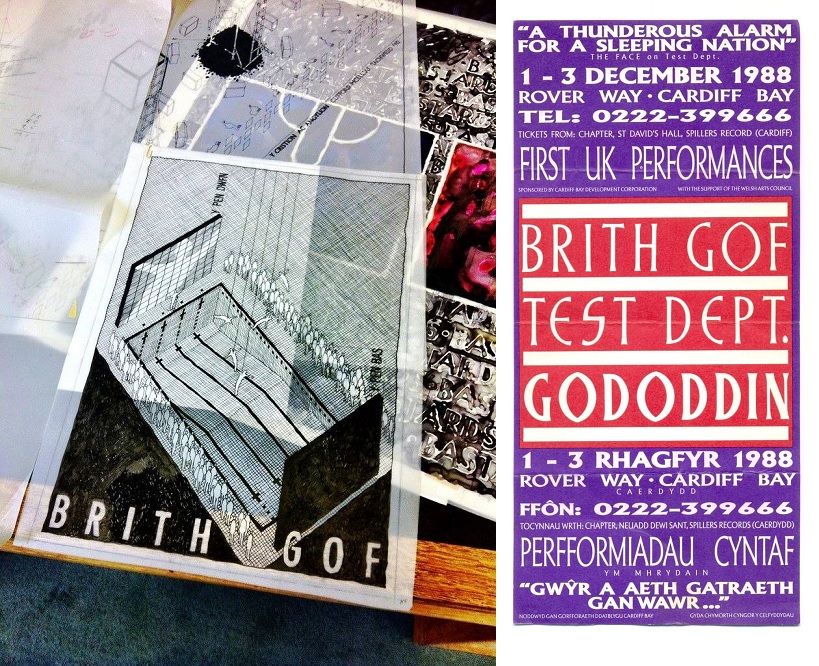

Who else would have managed to transplant the history and indeed the physical lay-out of the Hafod estate in Ceredigion to the former mental hospital in Ely, Cardiff or turn the medieval poem Y Gododdin into a theatre experience to rival anything by the likes of Robert Lepage?

The latter production, in a disused car plant was simply one of the most exciting, visceral and utterly astonishing productions I’ve ever seen.

It overturned one’s sense of theatre and many other things, not least your sense of one’s own national literature.

This wasn’t usual theatre. Queuing outside a great clanging factory space at night. Then, inside, there was the sheer bloody noise of it, not to mention Test Department’s throbbing, pulsing industrial music and the martial beat of the words, the clash of weapons and words and the swish of words swung like swords!

Old words, new theatre. Gwyr a aeth gatraeth oed fraeth eu llu. glasved eu hancwyn a gwenwyn, bellowing out of the past.

Mike Pearson could transmute and transform, turn abstract ideas into bodies moving in space, a serious, thoughtful conjuror able to bring new worlds into being, or at the very least to share world views which made you rethink what you knew of it.

He made maps you had to follow, taking in key points of interest such as Rhydcymerau, south Wales iron towns such as Tredegar, the Patagonian plains.

But he was also the lovely man, the unbridled enthusiast for life and its informations you always wanted to bump into in the park, where he would tell you about stuff he’d recently discovered or uncovered.

I remember him extolling the musical virtues of Tricky when the work of the Bristol producer and DJ was far, far from being well known.

He liked to talk about birds and how I wished a red-eyed vireo or a stray indigo bunting had appeared in the bushes to add a flash of rarity to the simple excitement of meeting Mike.

Capacious reader

And then there was Mike Pearson the avid, book-devouring reader.

In 2001 I read a wantonly experimental novel called House of Leaves by the young L.A writer Mark Danielewski and was so fired up by the experience that I went down to Chapter bar, eager to tell someone, to corner anyone who would listen to me enthuse about its mad energy.

There I met Mike who had, of course read this obscure title.

Others here pay tribute to the collaborator and the visionary theatre maker but I also salute a capacious reader and a very fine writer to boot.

Next to the bed I have one of the books he recommended, being A Book of Death and Fish by Ian Stephen, because if Mike gave his seal of approval to a book it would always be worth reading.

And then there were books he turned into performances such as the long poem Testimony by Charles Reznikoff – based on court records from the United States – from which he and his fellow artists read 6 hours’ worth for Experimentica at Chapter (with Ian Watson creating a soundscape) and a 4-hour version to mark the inauguration of Donald Trump!

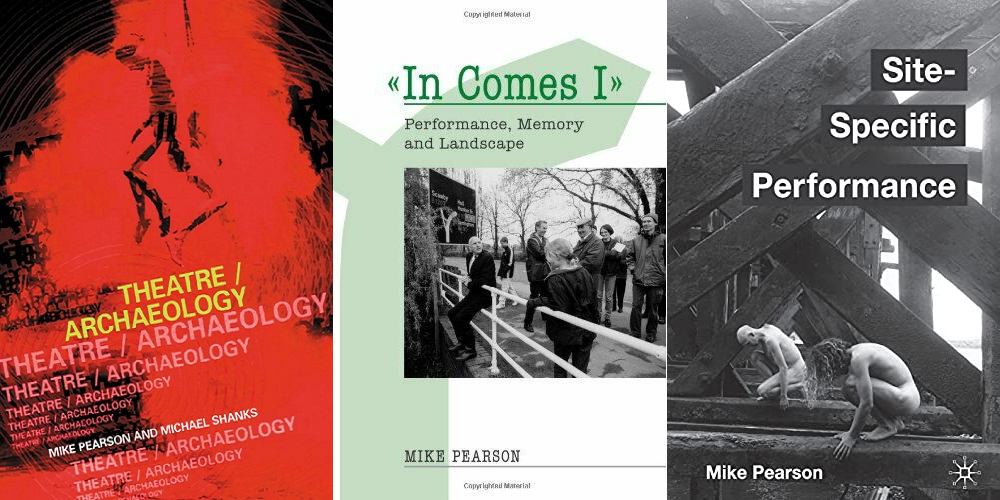

But then there are his own books such as Theatre/Archaeology, which he wrote with Stanford academic and fellow archaeologist Michael Shanks, which explores using the techniques of archaeology to re-create the sort of theatre works for which there are no scripts and looks at archaeology as a performance, pausing along the way to enjoy deep-mapping and so much more.

It’s a glorious hybrid of disciplines, fair bashing them together to produce a heady mix of ideas and I’ve lost count of the number of copies I’ve owned but given away.

Then there is In Comes I, where landscape writing mixes with personal memoir, folklore and accounts of the potato fields of Lincolnshire, not forgetting the performance spaces of his local chip shops, where he learned about rhetoric and oratory from the women serving there – his aunties I think.

A Renaissance Man? Most surely, although I venture he’d have politely shrugged off the label.

And one who catapulted Welsh theatre and its thinking into a whole new dimension and in utterly new directions.

John Hardy

Mike Pearson’s career has been so long, and with such varied elements of style, scale, tradition, topic and structural frame, that it is extremely hard to sum up the many and profound achievements Mike has led, participated in and mentored, through so many fields of performance.

Mike has cheerfully been all of the following:

Conceptual dramaturg; doctoral academic, inspirer of generations of students, and for many years Professor of Performance at Aberystwyth University; sober-suited and sometimes naked physical performer, sometimes with text, often without; forensically detailed and precise archaeologist of specific texts and historical documents; collaborator with strong fellow-artists, often because they specialise in different disciplines – visual design, architectural stagecraft, poets, playwrights, composers, experimental jazz musicians, dancers, disability & gender specialists, comics, community art conveners, museum curators, traditional Japanese theatre performers, Patagonian farmers, Welsh folk historians and wild creatures and their bones.

I first came across Mike in 1973 – I attended [as an impressionable teenager] a Sherman Arena performance of Mariner, a hugely impressive dumb show depiction, in vigorous physical performative style with a team of fit costumed colleagues, of the Coleridge poem.

The only use of words was in two solo songs. Everything else was vividly acted out in silence.

Soon afterwards I was able to see Gorboduc and Gilgamesh, all exuding rough male energy, though there were powerful roles for women too, and all using wordless physical movement as the chief theatrical language.

Soon after these works, performed under the guise of Cardiff Laboratory Theatre, I found myself drawn into the next series of performances for a decade, now bringing the silent world of no text and no music to life with songs, instrumental music and collaborations with a variety of brass bands, string ensembles, choirs, percussion, harmoniums, accordions and grand pianos.

Gradually, more and more carefully constructed spoken or sung texts started to appear, always learned by heart, until the impossibly long, nearly 8-hour, show Iliad [2015].

Immaculate performances

One of Mike’s purest and most perfect shows stipulated a maximum of eight audience for each of the immaculate performances. Whose idea was the wind? [1978] was lit by one single tea light.

This time a beautifully constructed text told stories from North American indigenous origin myths, with the help of a heron skull, some sheep wool, a porcupine quill, a crow’s feather, and a fir cone.

It remains one of the most memorable performances I have ever witnessed.

In Moths In Amber [1978] pre-recorded music started to make an appearance, and by the time we arrived at The Disasters Of War series and Gododdin, ten years later, now under the Brith Gof brand, loud and powerful pre-recorded soundtracks were added to, with live musical performance, while the ‘acting’ or ‘physical performance’ group achieved bigger and more impressive feats of leaps, pole vaulting, crashing into walls and siege nets, lifting each other into impressive human pyramids, repeatedly falling into cold water which made their kilted bodies steam like industrial machines or battle horses, and lying defeated among ruined cars and a forest of indoor fir trees, while audiences stared on in shock and sympathy.

Pandaemonium, staged in April 1987 at Tabernacl Treforys/Morriston, the ‘cathedral of Welsh Non-Conformism’ took the two mining disasters in Senghenydd [1905, 1911] as the starting point for a show that began as a chapel service that is interrupted by news from the mine, and developed into a furious argument about the causes of the accident and an inclusive ritual of community grief.

Accompanied by the chapel organ, an all-singing cast including the great Heather Jones, a Hammond organ and three local choirs, the audience ended up being unable to avoid being swept along by the action, and the singing.

Patagonia

Always connected with fellow practitioners in other countries, Mike was being invited to conferences and festivals in places like Zagreb, then behind the iron curtain, when still in his mid-twenties.

In 1977 he was invited to star in a new show [while visiting The Mickery Amsterdam], by the Pip Simmonds Theatre Company, then one of the most respected experimental theatre/performance companies in Europe – which he declined.

Instead of becoming a performer for hire, Mike came back to Wales, gave up smoking, learned Welsh, started to drive, and then devoted several years to building a theatrical and cultural presence among the small communities and villages, chapels and farms of Ceredigion and Carmarthen/Caerfyrddin, along with the early pioneer members of Brith Gof, including Lis Hughes Jones and Nic Ros.

There was a journey round the region of Argentina that was settled by Welsh speaking pilgrims from 1865 – Patagonia – which was a powerful influence on the work of Brith Gof.

Later, in 1992, Mike’s application to the Barclays New Stages Award received funding to create Patagonia, a stunningly original show, in Welsh and English mixed together, telling the story of the Welsh settlers with action, monologues, choral speaking, much singing, and a pre-recorded soundtrack that culminated in the appalling death of community leader Llwyd ap Iwan at a village stores at Nant Y Pysgod, a tree-sheltered and well-watered spot in the wilderness, in 1909.

Almost certainly the murder was committed by Butch Cassidy and the ’Sundance Kid’.

This shocking and culture-destroying event became a running feature of many of Mike’s subsequent solo performances, one of which took place among the farm buildings preserved at Sain Fagan, the Museum Of Welsh Life.

From Memory, a long, complex, beautifully constructed text, which took the form of a guided tour around the extraordinary preserved historic buildings in 1992, was so much more than a feat of memory.

It established a new version of Mike’s way of entertaining his audience – by mixing historical and archaeological facts with details of Mike’s own family, origins, experiences and reflections.

Later Mike explored his native rural Lincolnshire in four hours of beautifully constructed sonic narrative and analytical observations, taking in history, geography, sociology, anecdote and personal recollections, in Carrlands [2007] and Warplands [2011], as well as a dramatic sonic essay on the weather of the Netherlands in Winter [2008].

(And this aspect of Mike’s own creative writing, though less-known and under-appreciated, continued to unfold into his seventies. Mike wrote copiously about Cardiff and dreamier locations during lockdown, under the aegis of a creative conversation with Ed Thomas and myself, and he continued to release filmed dialogues with younger colleagues and friends, and senior USA academics, among other activities.)

Intimate and expressive

While this more intimate and expressive work continued, Mike was also collaborating with other colleagues to create huge works which performed to mass audiences.

Gododdin was seen in 1988 and 1989 across Western Europe by at least 12,000, possibly many more.

Pax, in Bangor Cathedral, St David’s Hall, Glasgow Harland & Wolf Ship Works, and Aberystwyth Railway Station [1990 and 1991] was also seen and heard by over 12,000.

Each of these projects also saw released CDs, so the musical audience was extended, and a 60 minute documentary about the making of Gododdin was broadcast on ITV in 1992, and remains in archive.

Another massively ambitious large-scale show, commissioned as part of Valleys Live [1992] was also seen by large audiences from the Valleys and across South Wales. Haearn / Iron was performed in the vast historic iron foundry, now demolished, in Tredegar, dealing with the ideas of the industrial revolution in the area, and the myth of Prometheus bringing fire to human society, with the help of many physical performers, narrators, plus solo operatic soprano [Gail Pearson], three choirs from the area, the Tredegar Youth Brass Band, and, as usual by then, an enormous PA sound system. This featured in an S4C documentary Haearn in 1993.

Gradually Mike was beginning to focus his attention on writing and directing the shows, but no longer necessarily performing on the stage.

In fact increasingly the whole idea of a stage was disappearing, as performers, audiences, technicians, technical stage hands and camera operators and the directors, would be together in the heart of where the action was taking place.

The first show where we collaborated with the very new National Theatre Wales [2010], was The Persians.

This won various awards, including for the text – Kaite O’Reilly’s stunning adaptation of the world’s oldest surviving play, describes the destruction of the Persian fleet by the Greeks at Salamis.

As well as selecting the topic, and the source text [Aeschylus], Mike also brought to the table the fruit of his extraordinary research into the location [Tirabad] where this unique project was performed, surrounded by moorland, sheep, soldiers and wild birds.

FIBUA [a training centre for Fighting In Built Up Areas] is a model military village high up in the firing ranges of Epynt.

Some of the performances were heard through the patter of rain.

Others were miraculously illuminated by bright August/September evening sun, and accompanied by distant sheep calls.

Every performance was sold out in advance, and nobody who experienced the show, and its unique location, will ever forget it.

Another hugely ambitious collaboration [with NTW, The Cultural Olympiad, and the Shakespeare Festival], Coriolan/us, took place in an enormous 1939 aircraft hangar at St Athan near the South Glamorgan Heritage Coast.

A full promenade performance of Shakespeare’s Coriolanus, augmented by fragments of Brecht, was played out in an acoustic so reverberant that the audience listened to close-mic performers on ’silent disco’ style headphones, like a living radio play, with pre-recorded music and soundtrack mixed in, in real time, combined with nine live cameras capturing closeup views, wides, and fast moving travelling shots, just like in live TV coverage of a major sporting event, all shown on huge screens by two teams of vision mixers.

A very strong UK cast brought audiences from far and wide, and, again, those who were there will never forget it.

I could go on – to cover more recent projects such as Iliad with NTW in Fwrnes Llanelli, and various actions and interactions Mike has initiated or supported, in the past five years.

Perhaps most notably his beautifully written English language account of the death of Phaeton, son of Apollo, for NTW Storms 1 [2018]; and the incredible feat of forensic urban archaeology, historical research and hunting down of photos of criminals which Mike achieved over two years of investigation to create the first ever historically accurate, blow by blow account of the Cardiff Race Riots 1919, initially performed as NTW Storms 2 [2018-19].

Coriolan/us

But I’d like to leave the reader with an image of the way Mike works.

Two weeks before the first rehearsals of Coriolan/us began, in June 2012, after over a year of regular meetings with Mike to discuss aesthetics, textual structure, music and sound, and other aspects of planning, I was invited to visit Mike one Sunday afternoon at home.

By this point, the beautiful scale model of the venue had been made by Ruth, then a design student at RWCMD.

All the cast, caravans, vehicles and obstacles were depicted and were present in detailed figures and objects on the floor of the large stage model.

Mike sat me down and talked through the structure of the entire five-act play, scene by scene, moving every character and vehicle according to a precise itinerary, entirely from memory, from beginning to end, without a break.

On the first day of rehearsal, the actors, to their surprise, found that all details of their performance had been considered and calculated in advance – all they needed to do was learn their lines and find the energy to keep the rapidly moving crowd scenes and more intimate moments moving back and fore across the vast territory of the venue, according to the microscopically devised plan, drawn up by Mike, and his co-director on Coriolan/us, Mike Brookes.

By the time the show was up and running, Mike was often to be found, behind the control hut inside the hangar, with his disco headphones on, eyes closed, sitting and listening intently to the whole performance like a live radio drama.

Mike was someone who managed to create a unique and bespoke relationship with each of the friends and colleagues he spent time with.

Each of those hundreds of people will have felt that Mike’s attention was on them. We all feel he cared about us as individuals, and many of us have little or no idea about many of the other people in his life.

As he got older, his kind care and appreciation seemed to extend and deepen.

Many have felt validated and uplifted by Mike’s support, appreciation and encouragement, of them, their interests and their work.

His own work may not be fully known in England, except perhaps among geographers; but in Wales, including through the continuing work of dozens of Welsh performers, and in Europe, and the Americas, his work and his influence live on.

Lis Hughes Jones

It was in 1977 that I first met Mike, the quietly spoken and charismatic man who introduced me to his world of physical theatre.

I soon gave up my doctoral studies to make performances with him, initially joining him at Cardiff Laboratory Theatre.

Then in 1981 we co-founded Brith Gof in Aberystwyth, where we lived and worked together for much of the 1980s. It was an extraordinarily intense and creative decade.

Mike’s endless curiosity, breadth of mind and remarkable imagination drove our work. He was the director, the conceptual thinker, the magnetic performer. I was the maker, the writer, the singer, bringing my cultural heritage as a Welsh speaker to this new form of performance we were co-creating.

He learned Welsh; I learned the craft and discipline of physical theatre.

We wanted to make theatre in Welsh that reflected our roots in European Third Theatre. A theatre that spoke also for the generation of young Welsh practitioners who engaged in our process.

Among them were Matthew Aran and Nic Ros, who joined Brith Gof after graduating from the Drama Department of Aberystwyth University.

Good fortune

Our early work was rooted in the specificity of place and drew on stories, songs and images woven into the fabric of a particular location and its people.

That specificity, both in terms of language and of political and social focus, would speak later to wider audiences, leading to collaborations with theatre companies, musicians and artists across Europe and beyond.

The Disasters of War series was pivotal in the company’s evolution, with John Hardy and the late Cliff McLucas bringing new energy and vision which resulted in Gododdin, Pax and the emergence of site-specific performance as a widely recognised form.

From Branwen in Castell Harlech (1981) to Patagonia at the Royal Court (1992), via Rhydcymerau in the Old Bull Ring in Llanbedr Pont Steffan, Ymfudwyr in the dusty halls of Poland and Argentina, Gododdin with Test Dept in a sand quarry in Polverigi and PAX at Aberystwyth Railway Station, Mike stood at the centre of the Brith Gof’s innovation with courage, vision, humour and modesty.

Having left the company in 1992 I was touched when Mike invited me in 2007 to join him, alongside other former colleagues, in the foundation at the National Library in Aberystwyth of the Brith Gof Archive, which evolved into a landmark digitisation project.

It was my good fortune to meet Mike that day in the Sherman Theatre and to have played a part in the vast compass of his life. I am thankful to have had him and Heike as friends and neighbours during these last years.

Diolch i ti Mike – cysga’n dawel.

Eddie Ladd (Fersiwn Saesneg yn dilyn: English version follows)

Roedd Mike Pearson yn un o sylfaenwyr Brith Gof, cwmni theatr arbrofol oedd yn cynhyrchu sioeau Cymraeg eu hiaith ar safleoedd arbennig.

Rwy’n falch iawn fy mod wedi cael treulio degawd yn gweithio gyda nhw o 1990 tan 2000. Dylanwadodd nifer o aelodau’r cwmni ar fy ngwaith fy hun ac roedd Mike yn un o’r sawl ddysgodd bron popeth i fi yr wyf yn ei ymarfer tan heddiw.

Bu ‘na dipyn o rygnu dannedd nad oes gan y Gymru Gymraeg ei hiaith draddodiad theatr helaeth. Mae yna nifer o resymau am y diffyg hwn, ond credaf nad oedd Brith Gof yn ei ystyried yn golled.

Ni fynegwyd hyn i fi erioed gan neb, cyfreithwyr, ond mae gennyf gartŵn dychmygol yn fy mhen, mewn graffics 80au cynnar, ac yn panel cyntaf mae yna dri neu bedwar yn sefyll mewn stafell yng Nghanolfan yr Ysgubor yn Aberystwyth, lle sefydlwyd y cwmni, sain yn dod o radio a llais yn cwynofain nad oes gan y Gymru Gymraeg ei hiaith draddodiad theatr helaeth. Yn y panel nesaf mae yna ddwy lygad a swigen feddwl…a diolch am hynny…uwchben ei h/ael chwith.

Roedd Brith Gof yn perfformio ar safleoedd arbennig. Er i fi glywed Mike yn cydnabod fod adeilad theatr ei hun yn “safle arbennig”, roedd ei fryd ef a’r cwmni ar berfformio mewn llefydd nad oeddynt yn rhan o draddodiad dan do a cheidwadol the well-made play.

Felly, mewn sguboriau, capeli, hen ffatrioedd, gorsafoedd trên..ac, unwaith, mewn stadiwm hoci iâ. Nid oedd sgriptiau’r sioeau yn deillio o ddramâu.

Ym 1987 es i weld Gwir gost glo yn Nhreforys – yng nghapel y Tabernacl, cadeirlan y capeli – a chael fy nharo gan y sgript. Ar un pryd roedd Mike yn y côr mawr yn traethu yn ddi-dor, yn edrych lan at y galeri, ei ddwylo hirion mawr yn agored.

Nid wy’n cofio o beth yr oedd yn ei ddyfynu – ai o lyfr rheolwyr y gweithfeydd, y meistri glo? Ond beth oedd yn fy syfrdanu oedd yr ymdrech gorfforol i ynganu’r testun; roedd y geiriau mor fawr â chyfalafiaeth; roedd y testun yn dalp anystywallt nad oedd wedi cael ei lyfnhau a’i blethu i rediad o olygfeydd.

Nid oedd yna gymeriadau! Nid oedd y sioe ddim byd tebyg i How green was my valley!

Ges i fy nysgu gan Mike a Lis Hughes-Jones yn fy mlwyddyn cyntaf yn coleg yn Aberystwyth ym 1982. Roeddynt wedi eu trwytho mewn theatr gorfforol a’u dylanwadu yn bennaf gan theatr Bwyleg.

Wyddwn i ddim am y rhain ond ges i ‘roed yr argraff fod y diwylliant yr oeddwn i wedi ei fagu ynddo yn llai pwysig na’r byd theatr arbrofol hwn. Rwy’n cofio iddo’n cynghori ni, oedd yn ddosbarth cyfrwng Cymraeg, i ddefnyddio cydadrodd yn ein darnau. Roedd yn ffurf o’n i’n ei gyfri yn gapelog ac eisteddfodol, ond fe wnaeth i fi ei ystyried o’r newydd. Roedd holl gyfoeth ein magwraeth yn cyfri!

Roedd yn ddigon ynddo’i hun ac yn ffenomenon i’w blethu â theatr flaengar y cyfandir. At hyn, fe ddysgodd Mike Gymraeg ac roedd yn medru ein dysgu ni yn yr iaith. Wrth ymdoddi felly i’r ardal nid oedd yn iachawdwr yr oedd ei agwedd a’i waith yn rhodd i’r isel rai. Roeddwn ni wastad yn cloncan â’n gilydd yn Gymraeg.

Cartŵn arall.

Panel agoriadol: PAX, 1990. Hen safle adeiladu llongau Harland & Wolff.

Mae’r panel cyntaf yn dangos criw sylweddol o berfformwyr yn sefyll o gwmpas Mike Pearson. Mae rhai, yr angylion, â harnesi hedfan amdanynt ac yn gwisgo arfwisg kickboxer. Eraill o’r criw mewn siwtiau hazmat du neu wyn. Mae swigen llais Mike Pearson yn dweud

“Now, remember – “

Mae’r panel sy’n dilyn yn dangos ond ei wyneb, ac mae’n erfyn ar bawb i fod yn ofalus a phwyllog gan ei bod yn sioe fawr.

“- NO HEROICS!” dywed y swigen llais.

Mae’r panel nesaf o safbwynt un o’r angylion, sydd i gyd nawr fry uwchben yn y nenfwd yn aros eu tro i ddisgyn i’r ddaear. Mae’n dywyll ac mae pawb ar y llawr yn fach. Gall yr angel weld criw Mike yn eu gwisgoedd hazmat gwyn.

Mae’r panel nesaf yn dywyll hefyd ond â graffic gwyn ysgafn yn dangos dechrau’r trac sain.

“I fyny yn yr awyr..”

Mae’r panel nesa o safbwynt yr angel.

Mae yna swigen llais yn dod o lawr y safle.

“Wwwwaagchhh!”

Mae’r panel nesaf yn dangos pen moel Mike ac mae’n amlwg ei fod yn rhedeg.

Mae ei griw o berfformwyr i’w gweld yn cwrso ar ei ôl tu ôl i’w swigen llais.

“Wwwwwaaagchchchc!” ebe Mike.

‘Does dim o’i le. Ond mae’r heroics wedi dechre.

Pax oedd y darn cyntaf y gweithiais arno gyda’r cwmni ym 1990, slampen o sioe lle roeddwn yn hedfan mewn harnais. Roeddwn yn un o bump o angylion neu greaduriaid aliwn oedd yn glanio ar ddaear lygredig. Roedd Lis yn cydweithio gyda John Hardy ar y gerddoriaeth a’r geiriau a Mike oedd yn arwain yr ymarferion corfforol. Nid oedd yn rhaid i fi dyrchu i’m haliwn mewnol cyn mynd ati i greu’r goreograffi. Er mod i wedi cael blwyddyn gyda’r cwmni yn Aber, dyma pryd afaelodd pethau yno fi. Tasgiau corfforol oedd yn arwain, nid seicoleg, ysgogiad ac emosiwn, ac oherwydd hyn roedd y tri mor hawdd i’w cael. Fe wnaeth y technegau roedd Mike, a’r cwmni, yn eu harddel ei gwneud hi’n rhwydd i fi symud a pherfformio.

Cartŵn i gloi.

Panel agoriadol: PATAGONIA, 1992. Abertawe. Mewn theatr.

Mae’r panel cyntaf yn dangos Mike o’r cefn. Mae’n gwisgo cot ddu ffurfiol ac mae’n eistedd ar gadair uchel ar lawr yr awditoriwm sy’n ei godi at lwyfan y theatr. Mae’r llwyfan fel petai’n ddesg ac o’i flaen mae sgript gyfoethog sydd yn trin hynt y Cymry yno. Ef yw’r traethydd ac mae’n treulio’r sioe â’i gefn at y gynulleidfa.

Wedyn, mae yna nifer sylweddol iawn o baneli yn dangos y pedwar perfformiwr sydd ar lwyfan. Maent yn rhan o gyfanwaith o sgript, gwaith corfforol, gosodiad llwyfan a cherddoriaeth.

Y paneli olaf.

Gwelir Mike yn codi o’i sedd. Mae’n gwisgo ei het.

Nesaf, gwelir ef yn cerdded i fyny’r grisiau wrth ochr y llwyfan. Mae graffics du a gwyn yn dynodi naws organ sinema ddofn ac mae’r finale ar ei ffordd.

Nesaf, gwelir fod ei ddwylo, sy’n llond y panel, â chadachau arnynt. Ef yw Llwyd ap Iwan, rheolwr stordy a siop fawr yn Rhyd y Pysgod, ac fe’u llosgwyd mewn damwain yn ddiweddar.

Nesaf, mae’n cyrraedd y llwyfan a mynd tuag at ei stôr, sydd yn ffurf sgaffald.

Nesaf, mae’n croesi’r rhiniog. Mae’n amlwg fod yna gythrwfl tu fewn.

Nesaf, mae pawb sydd tu fewn, ac mae’n glir eu bod yn wystlon, yn ceisio ei atal rhag cael ei saethu gan Wilson ac Evans. Neu gan Butch Cassidy a’r Sundance Kid, yn ôl y sôn. Mae yna ffurfiau dramatig.

Nesaf, caiff Llwyd ap Iwan ei saethu ac mae Mike yn disgyn yn araf i’r llawr. Pen llanw’r darn.

* * *

I am so pleased I spent a decade working with Brith Gof between 1990 and 2000. The company influenced my own work and Mike was the one who taught me pretty much everything I have put into practice from then until now.

There has been much talk about the fact that Welsh language Wales does not have an extensive theatre tradition.

There are many reasons for this absence but I do not believe that Brith Gof saw it as a loss. This was never communicated to me, lawyers, but I have an imaginary cartoon in my head, in early 1980s’ graphics.

In the first panel there are three or four people standing in Canolfan yr Ysgubor in Aberystwyth, where the company was formed, sound coming from the radio where a voice proclaims that Welsh speaking Wales does not have an extensive theatre tradition.

In the next panel there are two eyes and the caption ‘And thanks for that’ just above the left eyebrow.

Brith Gof performed on special sites. Even though I heard Mike recognise that a theatre building was a ‘special site’, he and the company had a desire to perform in places where they were not part of the conservative tradition of a well made play being staged under a roof.

Therefore, there were performances in barns, chapels, old factories, train stations…and once in an ice hockey stadium.

The scripts for the shows did not derive from dramas. In 1987 I went to see Gwir gost glo in Morriston – in Tabernacle, that cathedral among chapels – and was struck by the script.

At one point Mike was addressing an unbroken stream of words to the gallery, his long hands open to the audience.

I do not recall precisely what he was quoting – was it from the colliery managers’ books, those of the coal masters?

But what astonished me was the physical effort to enunciate the text; the words were as big as capitalism; the text was a rough intractable mass which had been smoothed and sculpted and woven into a run of scenes.

There were no characters! The show was nothing like How Green Was My Valley!

I was taught by Mike and Lis Hughes-Jones in my first year at Aberystwyth in 1982. They had been immersed in physical theatre and principally influenced by Polish theatre. I knew nothing of this but I never had the feeling that my own culture was less important than this world of experimental theatre.

I remember Mike giving our Welsh medium class some advice, namely to include collective recitation. It was a form of utterance I connected with chapels and Eisteddfodau, but he made me think of it afresh.

The whole world of our upbringing mattered!

It was sufficient in itself and a phenomenon which could be woven into progressive continental theatre.

With this, Mike also learned the language so he could teach us in Welsh.

As he melded into the area and community he was never a saviour with the idea that his work was a gift to those he had come to live amongst.

We always chatted in Welsh, naturally.

Another cartoon.

The opening panel: PAX, 1990. The old Harland & Wolff shipbuilding yards.

The first panel shows a substantial crew of performers standing around Mike Pearson. Some, the angels, are strapped into flying harnesses and are wearing kickboxing armour. Others in black and white hazmat suits. Mike Pearson’s caption says

‘Now remember…’

The following panel shows only his face, and he is encouraging everyone to be careful and cautious as it is a big show.

‘…NO HEROICS!’ proclaims the caption.

The next panel is from the viewpoint of one of the angels, who are waiting way up high, near the ceiling for their turn to descend to earth. It is dark and all the people on the ground are small. The angel is able to see Mike’s crew in the white hazmat suits.

The next panel is also dark but with a light white graphic to indicate the beginning of the soundtrack.

‘Up in the air…’

The next panel is from the angel’s perspective.

A voice bubble rises from the floor of the space.

‘Wwwwaagchcchc!’

The next caption shows Mike’s bald head and it is obvious that he is running. His crew of performers is running after his caption. ‘Wwwwaagchcchc!’

There is nothing wrong. But the heroics have begun.

PAX was the first piece on which I worked with the company in 1990, a great slab of a show in which I flew in a harness. I was one of five angels and alien beings which were landing on the sullied earth.

Lis was collaborating with John Hardy on the music and words while Mike was leading the physical work.

I did not have to dig deep into my inner alien before starting to develop the choreography.

Even though I had worked with the company in Aber, this was when things really took a hold of me.

Physical tasks led the way, not the psychology, incitement and emotion, and because of this all three were so easy to find.

The techniques Mike and the company embraced and employed made it easy for me to move and perform.

A cartoon to close.

Opening panel: PATAGONIA, 1992. Swansea. In a theatre.

The opening panel shows Mike from the back. He is wearing a formal black coat and is sitting on a high chair on the floor of the auditorium which lifts him towards the theatre stage.

The stage is arranged as a desk and in front of him there is a rich text which deals with the fortunes of the Welsh in South America.

He is the narrator and he spend the entire show with his back to the audience.

Then there are a great number of panels which show the four performers who are on the stage. They are part of the composite of script, physical work, stage design and music.

The last panels.

Mike rises from his seat. He dons his hat.

Next, we see him walking up the stairs at the side of the stage. The black and white graphics denote the deep spound of a cinema organ and the finale is on the way.

We see that his hands, which fill the panel are bound in manacles.

He is Llwyd ap Pwan, the manager of a storehouse and large shop in Rhyd y Pysgod, and he has just been burned in a recent accident.

Next, he reaches the stage and goes to his store, made of scaffolding.

Next, he crosses the threshold. It is obvious there is some commotion inside.

Next, its is clear that everyone inside, who are all being held hostage try to ensure he isn’t shot by two men called Wilson and Evans.

Or by Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid according to some.

We see dramatic shapes, moving.

Next, Llwyd ap Iwan is shot and Mike falls very, very slowly to the floor.

The climax of the piece.

Richard Huw Morgan

I really do not want to be having to write these words now.

Not just for the obvious reason that I never wanted to write about Mike in the past tense, rather for the same reason that participating in Germanic style post-production interrogation and dissection of performances by barely conscious performers never appealed to me.

We all need some time to reflect, to grieve, to digest the implications both personally and for the future development of performance in Wales that Mike is no longer with us.

Now is too soon. But one thing we know in this digitally saturated world that we inhabit, ‘no comment’ doesn’t stop the story running, and the vacuum is prone to flood with abstract banality.

So, I owe it to Mike to try to offer some personal recollections of the man that changed my life.

I’ll start with a couple of firsts:

My first memory of Mike is in extreme close up.

It is December 1st, 1988, and I am standing with my then girlfriend in a freezingly cold shed in subrural Cardiff.

I’ve dragged her along to see one of my current favourite bands, the industrial percussion group Test Department.

But this is no ordinary gig.

Activated environment

It would be several years before I’d hear the term ‘activated environment’, but activated it certainly was, not just with extremely amplified sound, but with lights, trees, fire, water, sand, trashed cars…and with highly animated kilt wearing nutters soaked to the skin.

And here is an extremely tall, bald, semi-naked nutter holding part of a trashed car screaming in my face to get out of the way.

I don’t actually hear his words, but I know what he needs me to do. It is difficult now to remember the live experience, I’ve watched the Gododdin TV documentary too many times to distinguish between the live and the mediated.

What I do remember is that I went back the following night to experience it all over again, without my girlfriend.

This was my first encounter with Brith Gof. I’d never had any interest in theatre. But this wasn’t theatre was it? It was real.

What I immediately recognised was the teamwork, the humanity, the tactics, and yes, the reality.

Here were performers coping with, rather than mastering, circumstances, collaborating with colleagues if the face of material adversity, with that adversity including members of the variously comprehending audience.

At the time I was working as a press officer for a variety of environmental organisations and the parallels struck home.

Friend and mentor

The first time I speak with Mike is at the two-day audition for Brith Gof’s next large-scale work, PAX.

I’ve seen the poster for it in Chapter, phoned up and explained I’d really love to audition, but can only come along on the Sunday, as I’m speaking at a British Association of Nature Conservationists event in Aberystwyth on the Saturday.

I’m told this is fine. I’ve never done an audition. I’ve only ever taken part in one community play.

Asked to do my ‘normal warm up routine’ I stand leaning on the wall as lithe and Lycra clad bodies contort. I’m thinking this is not the place for me.

In the afternoon dangling from the rafters in a climbing harness, I enthusiastically explore the possibilities of airborne embrace with a fellow auditionee and jump at the chance to repeat the exercise with the ‘spare’ body when Mike asks for a volunteer.

A couple of days later I get an unexpected phone call. It’s Mike.

Could I come to the Brith Gof office. He’d like me to be in PAX. He’d like me to be an angel. Ok, I’ll probably be hanging around in the background, but great.

The debut will be at St David’s Hall as part of the Cardiff Festival, the wage will be…hang on, I didn’t realise that this was a job, or that basically the performance WAS the angels.

If only I’d been at the first day of audition. Good job I’m not afraid of heights (sic)

And so began more than 30 years of Mike as a colleague, friend and mentor.

Since his death thoughts and memories keep coming, in no particular order, and mainly they do not come in words.

Some come in sound, or gesture or smell.

Smells of performance: of bleach and garlic and pilchards, of semi-cooked chips. Smells of Mike’s long term diet; of Dry Roasted peanuts and Diet Coke.

Some come in body memory, and physical pains and scars.

And then some words come.

Exotic words encountered for the first time, proxemics, haptics, praxis, pedagogy, bricolage.

Others we share an enthusiasm for, detournement, derive, psychogeography.

Not as a handbook or a blueprint, rather an appreciation that radical art could result in radical action…perhaps.

And then the phrases come:

“Nobody told us what theatre should look like”

“That might not be uninteresting, might it not?”

“Boys, I’ve had an idea!”, before paraphrasing something John or I had said to him a few days before with no visible response.

And, “No heroics boys!”, before charging off into the fray.

Rhizomically linked

Mike was always a supportive and willing participant in work that John Rowley and I have made over the years: forensically examining the unfolding chaos of Caucus on-stage, as a sleeping Howard Hughes in the 24-hour hotel room work Loop, contributing Japanese Noh singing to Lleisiau, replacing the unavailable Louise Ritche in Phantom Rides.

Mike often told us he was our number one fan, and it’s probably not surprising as we, like many others that worked, or studied, with him are rhizomically linked to him.

We may not produce the handbooks, beautifully handwritten index cards, endless revisions of lists, etc, but while it might not always be apparent, our working methodologies of structure, of dynamics, of scale, and the sometimes abandonment of these rules, is inextricably linked to Mike pedagogy.

And, perhaps most poignant, there are the conversations that were yet to be, that will never be had.

Less than 3 weeks ago he excitedly told me that he would soon have interesting news for me after his forthcoming meeting with National Theatre Wales.

I told him that I wanted to talk more with him about a discussion I was planning, to include him, Ed Thomas and James Hawes in a YesCymru conversation about the cultural and artistic impact of Independence for Wales.

These are the things undone.

Yet regret has no place here.

Today we witnessed the performance by Good News For the Future, a group of over 60’s performers, both previously experienced and unexperienced, working with the “In All Languages” technique that had been devised by Mike, John and myself in a studio out the back of Chapter during some Brith Gof downtime back in the early 1990s.

Planned prior to Mike’s untimely death, today’s work could not have been more perfect as the ensemble were joined in the performance by a 2-year-old from the audience.

She understood perfectly that there were structures and rules at play here, that these structures and rules were to be played with, and that nothing was, or ever is, fixed or certain.

Louise Ritchie

The care and attention Mike gave to everything was remarkable and this extended to his students.

I first met Mike over twenty years ago as an undergraduate student at Aberystwyth University.

I can picture him now standing at the front of the lecture theatre with a captive audience. He played Gododdin and that was it, the hair on end moment that opened up a world I didn’t know existed.

That moment and Mike’s continuous support and guidance changed my life; where I live, my daughters speaking Welsh, my career and how I think and see the world.

Conversations with Mike were always energising, wonderfully creative, and full of warmth, good humour and generosity.

One-off

He had an incredible ability to make you feel that your ideas were important.

I always came away from our chats feeling good and with a spring in my step.

More recently, my time with Mike was in a little box on screen, but even then, I can still picture Mike with his hand stretched across his chest, smiling or chuckling.

Mike was a one-off.

I’ve never met anyone like him, an incredible person who understood how to share with others and communicate complex ideas without losing his audience.

Mike enriched my life, and I am forever grateful to him for his wisdom and kindness.

I owe so much to him.

John Rowley

I have now known Mike as a friend, employer and collaborator for 30 years or so.

I was kind of adrift when I first met Mike. I had recently ‘retired’ early from drama school before finishing my course, becoming disillusioned with its training methods and where they would lead me.

I wasn’t really interested in ‘the art of acting’ and found seeing plays at the theatre very tedious. All of that standing-around-in-a set-of-cupboards-and-sofas-talking-at-each-other-for-hours did nothing for me.

I was already interested in the works of experimentalists like La Fura Dels Baus and The Wooster Group.

To cut a long story short I ended up in Cardiff, auditioning for Brith Gof’s forthcoming epic, PAX. I didn’t get the job! I was considered too hefty (my word), too tall for being an angel!

However, I loved the look and feel of Brith Gof’s work and had enjoyed the audition so I wrote to Mike personally and told him I wanted to be a part of the work in any way possible. I told him that I was prepared to work for free.

Mike wrote back, generously offering me a job, a paid job and so I got my first professional gig, riding a bike onto the stage of St. David’s Hall at the very beginning of the show, dressed in oilskins and welder’s googles that, pretty much, prevented me from seeing a great deal of where I was going.

And Mike and me hit it off straight away. We ‘got’ each other. We liked each other. It was a great relief for me to know that there were people out there like Mike. Although, to be fair, there isn’t/wasn’t really anyone like Mike.

I am biased but I think he was pretty unique.

Just take a look at his CV if you need to know the breadth of his talents and experience in the world.

Demanding work

I went on to make many shows with Mike and Brith Gof over the next decade.

The work was exciting and thrilling to be a part of. There was nothing like it. It was tough, physically and mentally demanding work. Often like going into battle. A lot of sweat was spilled…and, frequently, blood!

In Prydain, I was shoved out of a van into a cold derelict factory. I proceeded to cut my suit off with a Stanley knife, revealing my naked body emblazoned with the words of William Blake upon it written in indelible ink.

Mike then blindfolded me, thrust two hefty antique books into my hands and set them alight with lighter fuel before pushing me into an unsuspecting and terrified audience, leaving me to find my own way out of the situation…I smashed straight into a scaffold pole! Oh boy, those were the days!

The thing with Mike was that, although he was the Director, he didn’t really like directing performers as you would in much of traditional theatre.

He found performers he could trust to work instinctively within the framework and aesthetic that he created for any given piece without telling them, minute by minute what to do.

He had a firm grip on a production and always came armed on the first day of rehearsals with a whole series of cards filled with details of physical action and timings and diagrams of intended audience/performer interactions.

But he wasn’t one of those ‘dictator’ directors. He used what you had to offer. This was generous directing. I enjoyed the freedom of working with Mike. He was a big fan of free jazz and improvisation and he brought that into the work. Working with Mike on these productions was like having an apprenticeship.

You learned everything you needed to know about performing, especially what to do with your body in space and in relation to audiences. 360-degree performance. Mike was a real expert in the performer-audience relationship.

There were no innocent bystanders in a Brith Gof show. We literally were frequently ‘all in it together’!

A hearty laugh

When you’d first meet Mike he could come across as quite intimidating with his tall imposing frame and his bald head (something we shared).

And he’d often not say a lot to start with. He was quiet. He was, at times reserved. But once you got past this he was the opposite of what his appearance might have suggested.

He was incredibly warm hearted and friendly. He was funny and liked to laugh. He laughed a lot. A hearty laugh. Many a time I saw him spit out his tea with laughter. He was very human. When my boys were younger they used to refer to Mike as Nosferatu after the silent movie vampire created by Max Schreck.

But he really wasn’t like that BUT he would have made a great on-screen Vampire!

Mike liked nothing better, especially after rehearsal or a show, than to sit and drink with a close group of friends and tell stories. All kinds of stories, especially from his childhood in Lincolnshire. Often quite grim stories.

Sometimes you’d have heard the stories before but we didn’t stop him as he was enjoying the telling so much. You’d just enjoy his enthusiasm.

Sometimes he’d realise that we’d heard it already and he’d groan and say, “Oh boys, you should have said. I don’t want to bore you!”

Mike never bored me. Mike, the font of all knowledge. The ‘Prof’ as we often referred to him as. You could ask him about most things, especially natural history and he would have an answer or would find it out for you and send a link in an email as soon as he found out.

Looking forward

We would regularly meet up, even until the week before his untimely death. He was a good friend to have. We’d always text each other on a Monday morning and write “Coffee?” Although we never drank coffee. Always tea, and sometimes cake.

Mike liked cake. In the early days we would often eat in Bab’s Bistro down in the docks near Brith Gof’s old office.

While the rest of us would tuck into some greasy fry up Mike would nearly always go for a big slice of sugar-coated bread pudding. That was his lunch.

My Mum used to send him some in the post, wrapped in silver foil, all the way from Essex. Funny Mike. Unique Mike.

We’d sit in Chapter, (or Crapter as we’d sometimes call it if we were feeling slightly uncharitable) and talk about the TV or films we had seen over the past week.

Mike had a great memory for the names of actors and remember scenes from films in detail. He would recommend books that he’d read about in the London Review of Books or music that he had come across in Wire magazine.

We’d discuss ideas for shows that we might make in the future. We were actually about to start work on a new National Theatre Wales produced research and development period.

It was all looking very exciting for us after having had to stop work for the past couple of years due to Covid and associated lockdowns. We were looking forward to being back in the rehearsal room together again.

Mike had so much more to give to the world. Performances we will now never get a chance to see. Only imagine what he might have created given the chance.

Mike has left a huge impact on so many people whose lives he has touched. I feel truly privileged to have had him in my life for as long as I have. I will miss him dearly. There is a really huge Mike-shaped hole in the world. I hope people will take the time look back on the long and illustrious career, achievements and life of Mike Pearson and just go “Wow. What an incredible human being. What a life!”

And Mike’s words of encouragement/instruction will forever ring in my ears, which he would always shout at us as we left the dressing room before entering the ‘arena’ of a show site… “NO HEROICS BOYS!”

He wanted us to be careful, not to get too over excited.

(which he and we mostly ignored as the adrenaline rose up in us).

Diolch Mike. You were truly one of the greats!

Michael Shanks

It was 30 years ago that Mike arrived at my archaeology lab in Lampeter, University of Wales, with a video to show me – Pax TV – an experimental work from his company Brith Gof.

Layered frames and scanning cameras offered windows on a house in Wales and the woman who lived and died there. In this mélange of memory, media and event, Mike was an angel, Hermes. I didn’t see this then.

When Mike asked what I thought, I could only reply vaguely that it was a fascinating experiment in media and performance.

Mike said that he wanted to show me the video because it was archaeology – just as I had described in a recent book of mine about the archaeological imagination.

I didn’t know what he meant, and so started the conversation and collaboration between us that has been interrupted, that has taken such a sad turn with his death last week.

Mike was a performance artist, theatre director, theorist and philosopher, scholar and teacher, and, above all for me, an archaeologist, one who works with remains.

This is why he would appreciate my insistence that our conversation is not over: non omnis moriar, as the Roman poet Horace put it – death is no end to poiesis.

This reference to Graeco-Roman antiquity is clumsy. Not inappropriate, because Mike was always fascinated by the legacies of prehistory and antiquity.

Deeply composed

Traces in a landscape, the revitalization of the Welsh epic Y Gododdin, a radically reimagined recital of Homer’s Iliad, reworking Ovid, a site-specific performance of Coriolan/us.

And Mike was never clumsy. Always deeply composed.

Mike realized, embodied, performed what so many merely talk about.

How to connect the arts with research and cultural critique – research creation, research as arts practice, scholartistry.

Mike’s works informed so many agendas in critical theory, media and arts practice. A deep deconstructive questioning of the category of the human, of corporeality.

Performance design as an intervention in cultural politics, a transdisciplinary questioning of concepts such as landscape and belonging, urban dwelling, surveillance and social justice.

Mike’s works were sometimes spectacular and epic, sometimes small-scale multi-faceted gems.

Big themes and topics, and often also a personal voice – a production of Aeschylus on a military training range, an intimate chorography of a Lincolnshire village.

Very often they were produced with a wonderful team of collaborators, so talented in their own right.

Simply great and engaging, Mike reached diverse audiences in so many ways. Such an energy in this body of work – I have been so lucky to have shared the nomadic exploration, the incessant experiment, the intellectual roller-coaster.

Ed Thomas

(A translation of a tribute to Mike on BBC Radio Cymru’s Post Prynhawn)

Mike was unique, a pioneer blessed with vision, an intellectual rebel who was also funny and multi-faceted. Many people will remember him perhaps because of Brith Gof, the company he formed in 1981 with Lis Hughes Jones after their departure from Cardiff Laboratory Theatre before being joined by Cliff McLucas in the 1990s.

They often created work that was nothing short of enormous, breaking new ground in Wales even as they made their mark internationally, putting on unique and confident shows in places such as Glasgow and Milan, in anything from ice hockey stadiums to sand quarries and forests, or in huge factory spaces such as those found in the Scottish shipyards of Harland and Woolf.

I’ve not seen anything like it subsequently – it was like going to see the Rolling Stones or something and everyone looked forward to seeing such shows: this is testament to how clearly Mike could think and to the capaciousness of his imagination.

He had such a range of interests, too – he was a historian and a keen birdwatcher who would go off to see a sedge warbler when I had no idea what a sedge warbler was!

I remember him telling me when Brith Gof was at its peak – going to Barcelona and so on – wouldn’t it be great if we could put on a performance like the Neath rugby front row of the early 1990s, because he wanted a production to be that physical, like the hard rugby then played at the Gnoll.

Even though he was very clever and intellectual he was also a great friend, a very special man. He could do the little things in order to make sure that the big things worked and he could and would pull people together.

Gift for collaboration

He had such clarity of ideas and was so original but he also had a genuine gift for collaboration, for working together with others, sharing ideas, nurturing talent along the way, such as the time when he was a professor in Aberystwyth but also managing to do so when he was performing at a very high level indeed.

Mike was as thoughtful as he was kind, always willing to help anyone.

He saw no difference between doing a show in front of 30 people in Cwmgiedd, Ystradgynlais or in a working sand quarry in Lombardy with 3000 people in attendance.

The small things were for him the big things, be that presenting work before an international or a domestic audience, in say, a crane factory in Hamburg or in various places such as the bustle of Lampeter cattle market or the echoing cage of the Rover car factory in Cardiff.

Over the years he followed his own path, working with Brith Gof or composer John Hardy, always earning the audience’s respect, an audience that looked forward so very much to the shows.

It wasn’t made up just of young people, it was a cross-section of people, some of whom had no interest in conventional theatre but wanted to see live performance.

So even though some traditionalists might have wanted to throw brickbats or even stones at his ideas in the beginning, Mike won them over through the work itself and because of the clarity he showed in the making of it and by managing to be genuinely experimental and ambitious without alienating people.

That was clear from such work as Coriolan/us for National Theatre Wales at RAF St Athan and The Persians, staged on the Mynydd Epynt in mid Wales.

Here the army had built a fake Bavarian-style village to practice close contact urban warfare and only Mike could have persuaded the M.O.D to allow him to do a show on a bombing range, with the audience arriving by bus – that audience whose interest he had consistently engaged, entertained and maintained throughout the years.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Diolch i Jon Gower am ofyn i mi sgrifennu am hwn. Thanks Jon Gower for asking me to contribute. I am blown away by the words shared here. Diolch o’r galon i Nation.Cymru for publishing this. I hope there can be many more long form articles in the site x