On Being a Writer in Wales…and Northern Ireland: Angela Graham

Angela Graham

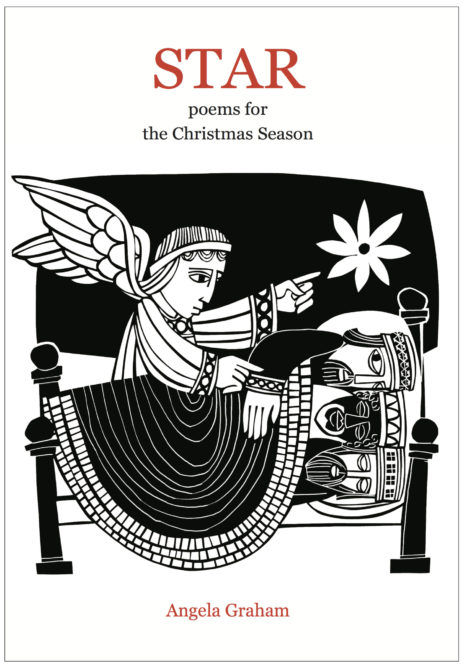

My new collection, Star: poems for the Christmas Season contains, alongside the English, some Welsh, Irish, Ulster-Scots and Scots. Mae’na dipyn o hanes tu ȏl i hyn.

There’s a backstory here.

I was born and bred in Belfast. Aged twenty-four, I married a Welshman and came to live in Wales. Within the year I had begun learning Welsh and was working as a tv researcher. In the divided society I came from, even nuances of accent were significant, so I felt it essential to open myself to that language I didn’t know.

Documentaries

My job introduced me to every part of Wales and a wide range of its people. I became a maker of documentaries, those evidence-based films which privilege helping people express themselves. I moved into drama and was the producer and co-writer of Branwen, an award-winning feature film in Welsh, English and Irish, set in Northern Ireland and Wales.

I also committed myself to media policy development in Wales because I knew from my upbringing how important ‘political’ frameworks are.

I was always writing poetry and fiction but seldom seeking to publish – no time!

Words and language have always been of absorbing interest. In my Catholic childhood, Latin and English faced each other on the pages of the Mass book, and there was Greek there too.

We encountered Irish in school. So I always knew that there is more than one way to address the world. I’ve worked also in Romanian, French and Italian. I struggle with these but I’m not afraid of language. I’ll give it a go.

Change of direction

As I approached sixty, I decided that I’d have to make a decisive change of direction if I was ever to be a writer. On 29th March 2017 I chaired the IWA Cardiff Media Summit and the next day set off for Northern Ireland with a bundle of short story drafts, determined to craft a collection.

A Literature Wales Writer’s Bursary that year had allowed me to work with Gwen Davies, editor of New Welsh Review.

By the shores of Strangford Lough I grappled with her insights into my subject-matter: violence, and the act of witnessing. That shouldn’t have surprised me, but it did.

A City Burning, the resultant collection was published by Seren Books in 2020 and longlisted for the Edge Hill Prize.

Language politics

An Arts Council of Northern Ireland bursary funded me to return to Northern Ireland to research material for a novel. I went with my antennae up, to pick up whatever was in the air – language and the politics of language, specifically Irish and Ulster-Scots. Language, as I knew from my experience in Wales, can be weaponised.

Conflict over language was a major factor in bringing down the Northern Ireland Assembly in 2017.

Barriers

But, from Wales, I had also learned that barriers can be dismantled and language used constructively. Wales had made learning Welsh easy for me. Encouraged by that, I resurrected my latent Ulster-Scots – not easy when there was almost no language tuition, much prejudice against Ulster-Scots, a tendency to assume speakers were Protestant, and some defensiveness among certain of its proponents.

If you’re not in, you can’t win, had been my best friend’s mantra at school. With that in mind, I entered and won the Poetry Prize in the inaugural Linen Hall Ulster-Scots Language Competition in 2021.

I wrote the first draft of a novel embedding the neuralgia over language and culture in a rural community impacted by city-dwellers. I included some Ulster-Scots in A City Burning and in Sanctuary: There Must Be Somewhere, my collaborative poetry collection published by Seren Books, 2022.

I now split the year between Wales and the town of my paternal grandmother’s birth on the Antrim coast, a mere twelve miles from Scotland. I was delighted this year to be a Makar o the Month for the Scots Language Centre. I’m working on a book of prose and poetry which has my paternal grandfather, Thomas Graham, an Ulster-Scots Protestant Unionist, at its heart.

So in creating a collection of poetry on the theme of Christmas it was natural for me to approach it partly in terms of language. It’s my way of working against any tendency to keep our indigenous languages apart or claim they are the preserve of only one sort of person.

Chrissmas Eve, in Ulster-Scots, set in Marks and Spencer’s in Ballymena, describes a shopper’s expectation of the Second Coming:

Tha manysther saes tha Sinn o God wull come

in pooer an glory, cloods reevit, tha sea aboil,

an tha stars teemed oot o haiven,

skailt lik leaves frae a crinnelt tree.

Whereas the encounter experienced among the fashion displays is tender and maternal.

In Nadolig I set three languages together. The words in each have the same meaning, but in varying shades, and their differing soundscapes provide sheer enjoyment.

NADOLIG

Nos

Seren

Addewid

Cyflawniad

Tywyllwch yn llawn lleisiau

Diwedd unigrwydd

Oíche

Réalt

Gealltanas

Fíorú

Dorchadas líonta le guthanna

Deireadh leis an uaigneas

Night

A Star

A Promise

A Fulfilment

Darkness filled with voices

An end to loneliness

A language can influence even without being directly present. Japanese is the moonlight glimmer behind my poem, Rescue. Liam Carson has rendered about a hundred of Santōka Taneda’s haiku into Irish. The opening of one of these stopped me in my tracks:

ní fhaca mé

an ghealach ag imeacht

dall sa dorchadas

In English:

i didn’t see

the moon going

blind in the darkness

Prompted by this, my poem begins:

I didn’t see the moon leaving.

My eyes were on the darkness gathering itself together underneath the conifers

like a foundered beggar wrapping himself in his own arms.

Linguistic horizons

Engagement with languages widens linguistic horizons. For instance, the original, Welsh-language words of All Through The Night are sinewy in contrast to the sentimental English translation. The line, ‘Golau arall yw tywyllwch’ (Darkness is another light) becomes, in my, Worship In Winter, Wales the spark which illuminates our need to ‘honour necessary darkness’ which is ‘that golau arall / other light by which we see the stars’ and ‘the womb’s lightlessness / and imagination’s cave.’

Being a writer in Northern Ireland links me to the culture of the whole island, an island of writers. Being a writer in Wales seeds me within a bilingual literary field which is blooming with an increasing variety of tongues. Support from both Arts Councils has been tremendously helpful. And I owe an enormous amount to the generous individuals in Wales and Northern Ireland who held, and hold, my hand in adventures in language and culture.

STAR: poems for the Christmas Season is published by Culture and Democracy Press.

It is available to buy from Gwales or from any good bookshop.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.