On Being a Writer in Wales: James Stewart

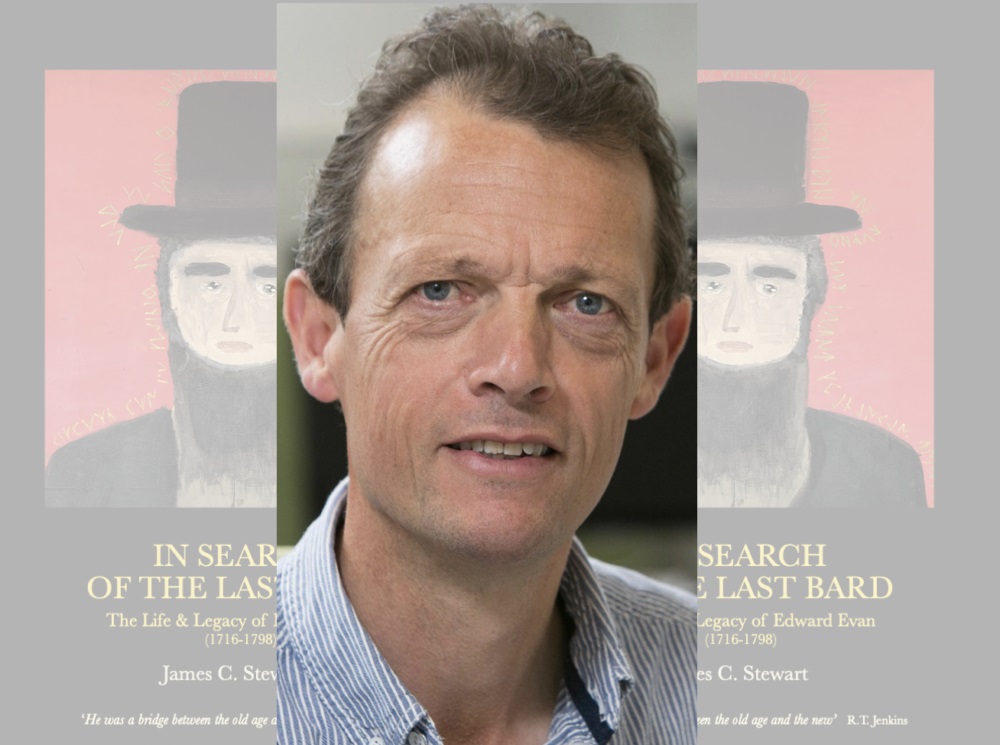

James Stewart

For almost fifty years I have been writing professionally in Wales, but the invitation to contribute to this series made me face the question of what it means to be called – or to call oneself – ‘a writer’.

From time to time, former students from around the world contact me with their reflections on the Masters course in International Journalism which I taught at Cardiff University in the last years of a career as a journalist. Often they tell me that, when starting to write a report, they ask themselves the question which I would pose to them in the School of Journalism: ‘Who is the real “who” of this story?’.

The roots of that question go back to the first days of my own training as a young reporter for the Western Mail & Echo in Cardiff in the 1970s, when those were real newspapers with big circulations and excellent writers like Mario Basini, Terry Campbell and David Berry.

The classic formula for story-telling was drummed into a group of graduate trainees in two rooms above a betting shop in St Mary Street – ‘Who, what, where, when, why and how?’

That formula has served me well in tackling many different sorts of writing, from daily news reports to scripts for radio and TV documentaries, first-person pieces for the late-lamented Planet to peer-reviewed articles for academic journals. In relation to that last category, I was struck years ago by the advice which Stuart Hall, the famous sociologist, gave to a friend who studied with him: ‘Whatever you are writing, you have to have a story to tell.’

Gwyn Alf Williams

No-one knew that better than the great Welsh historian Gwyn Alf Williams, who combined meticulous research with an ability to bring historical events and places alive through his passionate engagement with the people at the heart of the story.

He knew who was ‘the who’. When I worked for the magazine Rebecca in the early 1980s, it was a privilege to have Gwyn as a colleague when he wrote a series of pieces reporting on historical events as if he were a journalist observing and interviewing on the spot.

Gwyn Alf’s approach has been an inspiration in my most recent – and most demanding – writing venture which produced a book just-published by the Cynon Valley History Society, In Search of the Last Bard – the Life & Legacy of Edward Evan (1716-1798). My interest in this distant ancestor began with detailed family research carried out by an aunt. But her work resulted in an extremely dry account of the known facts about Evan’s descendants and very little about the most interesting character in the background – the real ‘who’ of the story.

Common people

Another inspiration was the work of Alison Light whose Common People succeeds in illuminating the lives of individuals who occur only as names, occupations and ages in census reports. Her ‘common people’ come alive and are just as interesting as the ‘uncommon’ and prominent people who are most often the focus of historical narratives.

I chose Edward Evan as my ‘who’ because enough had been written about him (though almost all in Welsh) to whet my interest, but I was faced with the challenge of researching a life lived at a time and in a place where one could not even find the limited information held in public records of census returns or baptismal registers

A poet, a harpist, a weaver, a farmer and woodsman, a carpenter and glazier, a radical ‘Dissenting Minister of the Gospel’, Edward Evan of Aberdare was well-known in his lifetime and became a legendary figure in the century after his death, when his Welsh poetry was popular in the newly-industrialised iron and coal towns of Glamorgan. A short biography was included in the fourth edition of his poems in 1874; R. T. Jenkins explored his life and times in Bardd a’i Gefndir (A Poet and his Background) in 1947; he is referred to in G. J. Williams’s Traddodiad Llenyddol Morgannwg (The Literary Tradition of Glamorgan) of 1948. Since then, and in English, there have been only passing references to Evan as a mentor and associate of Iolo Morganwg, in whose shadow he has faded from view.

Druidic bard

It seemed to me, however, that Edward Evan’s story deserved exploration because his long and varied career and his connections offered windows on many aspects of the ‘lost world’ hidden beneath the surface of industrial and post-industrial Glamorgan, where journalism had often taken me. My method was essentially journalistic, investigating the ‘what, where, when, why and how’ of his life, filling the many gaps with information from contemporary sources, academic research, and interviews with people whose experience could illuminate that life.

So I spent time with harpists, with a hand-loom weaver, with the last minister of the Unitarian Meeting House which was the successor to the Hen Dŷ Cwrdd where Edward preached, when he wasn’t farming or writing poetry. I wanted to know why his poems resonated with the Chartists of Aberdare and Merthyr in the 1830s and what were the roots of the legend that he had been the last ‘druidic’ bard from whom Iolo Morganwg had received ‘apostolic succession’.

In all this I set out to combine detailed research with a direct story-telling style. For the publishers I approached, it seemed to fall between two stools – too ‘academic’ for some, not sufficiently academic for others. I was fortunate that the Cynon Valley History Society liked the book and were happy to publish the story which I had wanted to write.

James Stewart’s In Search of the Last Bard: The Life & Legacy of Edward Evan is published by the Cynon Valley Historical Society. It is available to buy via: www.lastbard.wales or https://last-bard.sumupstore.com or the Cynon Valley History Society.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

James Stewart exposes the roots of Iolo Morgannwg’s ‘last bard.’ His forensic search retrieves Edward Evan from Iolo’s mythmaking, to narrate a real life lived on the brink of modern Wales. A true service to the understanding of our history.

History, as they say, is for the birds

Fantastic