On Being a Writer in Wales: Joshua Jones

Joshua Jones

I wonder what it means to lose your Welshness. What would that look – sound – like? It’s a question as heavy as the hand that holds the pen.

You’re beginning to sound English, my mother would say over the phone. What? Christ, I can barely understand you?, my English peers would say.

I moved to Southampton as an eighteen year old, for university, for art, community and punk rock, which I didn’t have in my home town of Llanelli.

In Wales I was at home in the rolling hills in my mouth, but in England I tripped over the long vowels that came from the back of the throat, the ‘ear’ that rhymes with ‘year’, the soft ‘h’ that accompanies a Llanelli accent (A fun example of the third one; for most of my life I thought I had an auntie called ‘Elen’, it wasn’t until a few years ago I found out her name is ‘Helen’).

Those rolling hills grew fog after a while. I couldn’t see them from the flat place, trying to figure out who I was and pay attention in my classes, or the world. Going home every few months on the train helped to clear the fog, but only a little bit, and for a short while.

It was like using the bottom of your fist to wipe condensation off the mirror, to get a better look at yourself. The invisible rope around my midriff pulled taut, and loosened as I made my way closer to home.

I moved to Bristol, and only when I was there, studying for an MA in Creative Writing, did I begin, naturally, to consider writing seriously. Up until then I had predominantly written poetry, outside of music reviews and academic essays.

In Bristol I fucked around; I allowed my friends to tattoo me on their couches, I moved from sublet to sublet, I worked jobs where I got paid cash-in-hand, I fell in love once or twice, I got jumped while walking home through Castle Park and saw God at 5am in the back of an ambulance.

I read and I read, and tried to write. I got carpet burn from the rope around my waist, connecting me to Wales.

Visual stimulation

Writing Local Fires was me attempting to give voice to my feelings of stagnation and observations of memory far removed from when I first experienced them.

During lockdown, I moved the kitchen table to the bay window overlooking the street, where I wrote the first drafts of stories that became Local Fires.

Where our house was positioned, in Horfield, Bristol, was directly opposite a turning, so I could see to the left and right of our street, and straight down the middle of the next street.

This was particularly affective visual stimulation – I watched neighbours barbecue meats on their front lawn, a bald man in Union Jack shorts and flip-flops trim the perimeter hedge every so often – while I mined my memories and experiences of home.

I began to work on the memories and traumas of growing up, of home, clumsy at first, like receiving a massage from an overenthusiastic but well-intentioned partner. One of the first things I wrote was of the death of a family member.

In Local Fires, death rears its head a number of times, but so does grief, mortality. The anxiety of living a life that doesn’t feel completely yours.

I think this is where a lot of my writing originates from; anxiety and preservation. What’s the difference between writing, and casting memory in amber?

Eyes of the world

I don’t need a desk, a specific room to write in, or time of day. I just need a window. I used to think it was about the view, but no. I just need a window. If eyes are the windows to the soul, then windows are the eyes of the world. I need to be able to look through one – and to be in view.

I like writing at night so I can look at my reflection, poised with laptop and research materials. I like to get a good look at myself.

Growing up I had no literary heroes from home to look up to, no artists or rockstars —all my favourite singers were American men with long hair and dresses — the closest to feeling represented within literature, was Dylan Thomas.

Specifically, his good humour, both within his writing and personal life, his keen observance of daily life and his love of sound to compose writing that is a delight to read out loud.

I knew of no writers or artists of any sort from Llanelli until I returned to Wales, to live in Cardiff, just a few years ago. I didn’t know of writers such as William Glynne-Jones.

I felt like I existed in a vacuum, a hinterland of sorts, between the physical geography of the town, the evidence and memory of the past in the minds of my parents, and the landscape of Welsh psyche.

William Glynne-Jones was a lone voice when Swansea, Cardiff, and the South Wales valleys were producing writers at a rate level with their factories. Perhaps being a Llanelli writer , if such a thing exists, is to be alone.

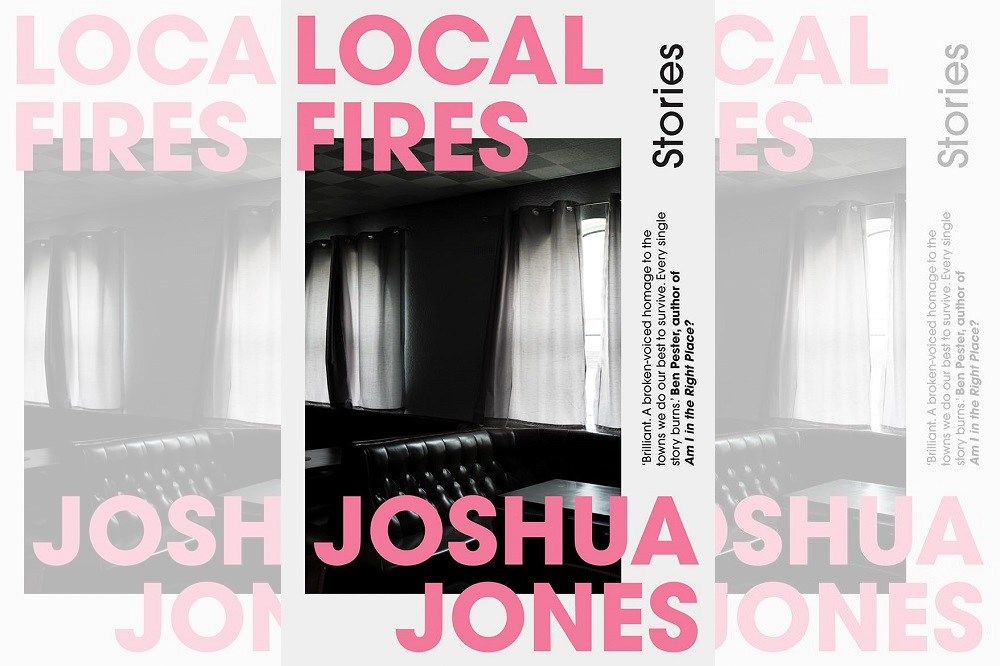

Local Fires by Joshua Jones is published by Parthian Books. It is available from all good bookshops.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

A brilliant piece of writing, and a really riveting read. Diolch, Nation.Cymru for bringing us these pieces and for fostering talent.