On Being a Writer in Wales: Martin Crampin

Martin Crampin

How do we define ourselves?

Twenty-five years ago I would have simply described myself as an artist, by which I meant a visual artist. Artists habitually do lots of things and I subsequently began to append Designer and Photographer after Artist, partly because I was looking for work. I concluded that designers and photographers were more likely to get work doing those things, than artists who do artist things, even though in practice my work as artist, designer and photographer naturally interwined.

Having written for various forms of electronic media and produced a couple of academic articles, in 2014 I published my first book, Stained Glass from Welsh Churches. Was this now the time to call myself a writer as well? As the designer of the book, which contained about 800 of my photographs (I was also completing a practice-based doctorate based on my work as a visual artist at the same time), was this the time to add writer to the header of my website and my email signature? Was it a label that might bring me new work?

Realising that there was a significant new string on my guitar, I opted instead for historian, rather than writer. A perceptive friend told me that I was a historian around twenty years ago, and having written a history of a branch of visual art, by this stage I was beginning to understand that I was an art historian, a term that I had avoided in the past. Despite having produced a book of nearly 350 pages, I didn’t feel as though I could claim the status of a writer, or had attained the proper mastery of that craft.

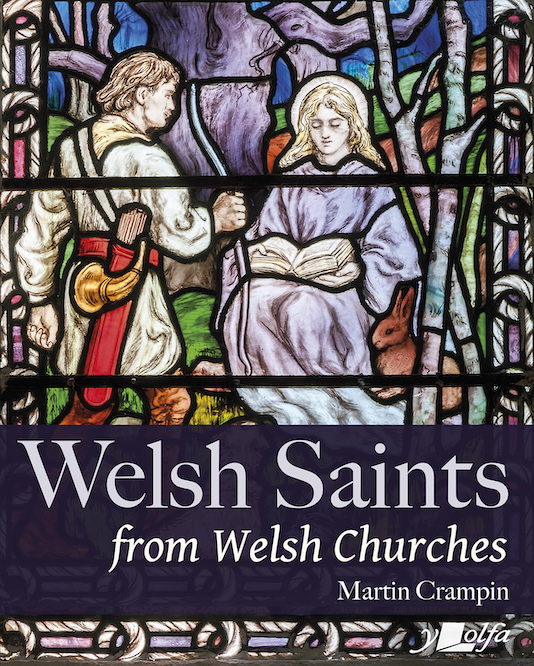

Now, in 2023, and much later than I anticipated, my second major book, Welsh Saints from Welsh Churches, has been published. I also have a few more articles to my name and a growing collection of smaller books published under my own imprint, Sulien Books. These are studies of stained glass at individual churches and a clutch of limited-edition books of my own images based on aspects of medieval decorative art. Is it now time to also afford myself the distinction of a writer?

When I was still at school and not yet in Wales I did think of myself as a writer. I wrote poems and a few short stories and won a prize or two. Some of these poems were published in various places, written, perhaps portentously, under a Welsh pseudonym, but that all stopped for various reasons by the time I came to Wales as an art student. By the time that I was writing short texts about artworks for CD-ROMs, a DVD-ROM and an online database in the first decade of this century, I knew that I could write well enough. I was aware of the need for clarity and brevity, for well-chosen words, but I didn’t feel that made me a writer.

In around 2010 I committed myself to writing a book on stained glass in Wales with a degree of trepidation. I convinced myself that it would be like a series of illustrated talks, based on the research that I had done in a few hundred churches. But the development of the narrative kept making me ask new questions, which I endeavoured to answer but usually entailed visits to many more churches all over Wales, which led to new discoveries that instigated further questions and more visits.

The purpose of the words was to explain the context and relationships of the windows with other windows, but in my mind the book was always primarily a picture book, whose success I assumed would rest on the quality of the photography and the design. As if to confirm this, having seen the book so many people commented on how good it looked that I began to wonder if anyone actually read it. Had I managed to succeed sufficiently as designer and photographer that it didn’t matter all that much whether or not I was a decent writer?

In Stained Glass from Welsh Churches and in those that have followed, the writing is mainly an attempt to explain things well, to provide the background so that we can appreciate why artworks are what they are. There are always some subtexts as well. I want to suggest that artworks in churches are worthy of our attention as manifestations of art and piety and patronage and cultural memory that are found in town and country, in suburbs and lonely fields. These are also books about Wales, told through aspects of the visual culture of Wales – a field of study that I became immersed in after coming to work with Peter Lord at the Centre for Advanced Welsh and Celtic Studies in 1999.

Welsh Saints from Welsh Churches is a book about Welsh visual culture, demonstrating the range and quality of ecclesiastical art in Wales. It is also about saints, and this required navigation through recent work on the cult of saints in Wales and understanding the afterlives of those saints over the centuries. The book is also about the creation of local and national identities, the imaging of the medieval past and the relationship of the church to that past. These things are communicated in writing, and the choice and arrangement of the images creates its own parallel narrative.

The things that we do do not necessarily define who we are. Millions of people take brilliant pictures on their phones but would not necessarily call themselves photographers. Many of us write notes and reports and all kinds of things on the internet without defining ourselves as writers. A couple of books in, I realise that it is now faintly ridiculous to ask if I am a writer in Wales. The question worth asking is how to become a better writer.

Welsh Saints from Welsh Churches is published by Y Lolfa. It is available from all good bookshops.

For more information about Martin and his work you can visit his website.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Love your book on stained glass. It is fabulous. I will look out for your new book