On Being a Writer in Wales: Niall Griffiths

Niall Griffiths

I’m somewhat averse to historical novels, especially those from writers not known for their adventures in the genre; I mistrust their motives, and generally baulk at their delivery.

They whiff of the grasping for The Big Prize which has hitherto eluded the deserving author, and evince the poltroonly retirement from a world in whose accoutrements of mobile phone and portable laptop traditional and formulaic plot lines shrivel and die.

There are exceptions, of course; all of Cormac McCarthy’s novels, excluding The Road, could be classed as historical fiction; George Saunders’s Lincoln in the Bardo does extraordinary things to and with the genre.

And whilst I have some sympathy with the notion that we can’t really grasp where we are without some knowledge of where we came from, I would contend that this can be done, and oftentimes is, by a writer deeply rooted in contemporaneity and committed to working within it; as just one example, look at Jenni Fagan’s Luckenbooth.

History is what we live, not what we have lived.

All of this said, tho…you don’t really choose what or who to love, do you? It chooses you. You catch a passing tang of something alluring and unfamiliar and before you know it, you’re following, smitten and besotted, nose in the air and heart booming like Pepé Le Pew after his beloved skunk (a reference for the historians, there).

Wild West

So, I was sitting in The Sun pub in Dylife/Staylittle. I’d been there before, many times, but I’d recently read Michael Brown’s book about the area and so I was hungering anew for more information.

I read the legends on the gravestones that would’ve fringed the Chapel, when it stood (it was demolished and obliterated many years ago).

I looked across the scattering of dwellings that remain of the vibrant, multi-cultural town this once was, and I dwelt on the figure of Sion y Gof, to whom I’d been introduced by Brown’s text: where was he gibbeted? From which hill crest was he hoisted and starved and dessicated?

And I’d recently, and ravenously, watched and re-watched all 3 series of the HBO series Deadwood, and I was thinking: well, this is the wild west, isn’t it? Of the island of Britain, of the continent of Europe.

Once, this area was also full of horses and gunshots and people making claims and lawlessness and, even, as I was to find out, native Americans.

The indigenous Welsh would, of course, be avatars of the First Nations in any story set hereabouts but the First Nations themselves were an actual presence, a further part of the heaving human melange that once populated this place.

And this Sion y Gof feller…who was he, behind the scant primary evidence that abides?

What’s his real story, or, rather – and this is the real question for the writer, caddish and ignoble tho it is – what story can I attach to him, spin around him and make, in one way, real?

Little is known about him; I can invent. I can use. I can embellish and elaborate.

Ghosts

As I say, a specie of love is fallen into (or, more specifically, indulged in). So I followed Sion down my valley into Cwmsymlog, where apparently he had his origins (and which features in several episodes of Y Gwyllt) and whose environs I’d long been exploring in my life and writing.

I picked through screeslopes, spoils of mining activity, and I leant against the rust-scabbed relics of dead industry and tried to feel their pulse, hear their clanking echoes. I strained to hear the ghosts of wolves in the encircling misted hills.

A world being revolutionised; heavy industry being imposed, the furtherance and deepening of class hierarchies and pampered pleonexia and utterly ruthless exploitation of lives deemed dispensable to rapacity, all of this stuff embodied in the solidity of steel machines forcibly rammed into the earth.

And, in the middle of this, little Sion and his innocence, his doomed need for love (and never mind that, according to the scraps of evidence we have as to his character, he was probably a bit of a gobshite).

The contemporary relevance was obvious (I won’t elaborate on this here; I’ve already done that, in the book). And there’s the notion of dyschronia; you’ll no doubt have heard of the concepts of dystopia and utopia – well, they allude to place as uchronia and dyschronia do to time.

Golden Age

The furniture of the novel I was planning would not be coterminous – wolves had long been made extinct by the time Sion was born, for example – but some corrective was needed, I felt, to the Downton Abbey-esque, shire Tory, Faragey and Rees-Moggy whitewashing of history that was going on at the time (and still is), the bewailing of the loss of and the yearning for a return to some mythical Golden Age that never existed (and which, indeed, is bulletpointed on Eco’s 14-item list of fascistic warning signs).

Any country’s ‘Golden Age’ glittered only for a small clique of the powerful; for most people it was coloured blood-red and shit-brown. How so many people were seduced into longing for a time of their own immiseration will forever mystify me.

So, anyway, that’s an attempt at self-justification for writing the kind of novel I never thought I’d write and of the type which I have often disdained.

I won’t do it again, I promise; I’ve been infatuated several times with people inimical to my person and I’ve learnt my lesson now (perhaps: I mean, I have no crystal ball (or not one that works, anyway)).

I’ll accept any accusations of inconsistency, even hypocrisy, here; as I say, I couldn’t help myself. And besides, gibbeting is illegal, these days.

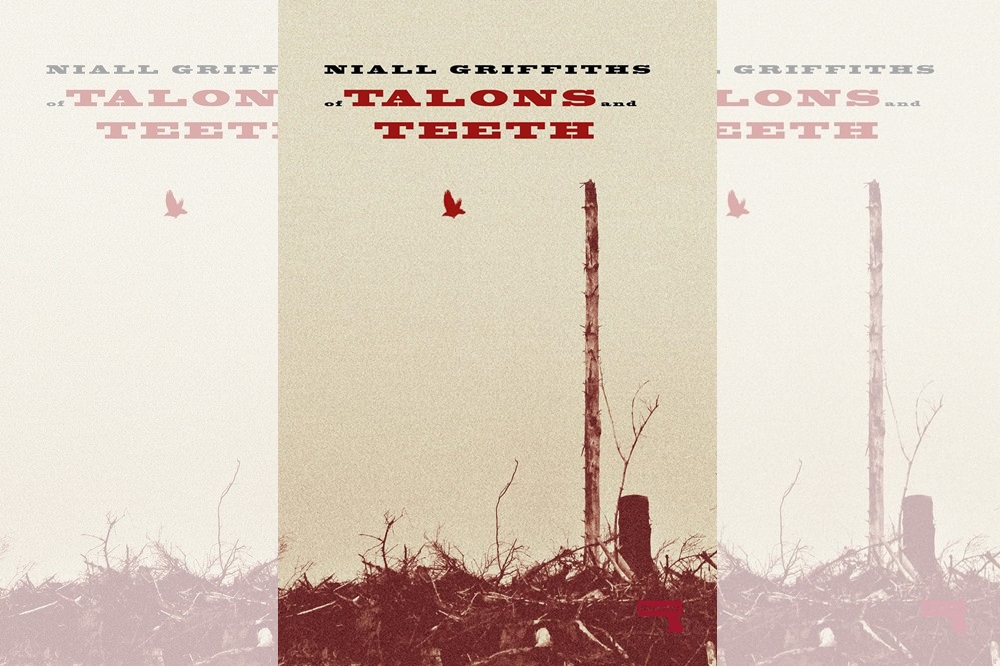

Of Talons and Teeth: A Novel by: Niall Griffiths is published by Repeater Books and is available from all good bookshops.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.