On (Not) Being A Writer In Wales: John Geraint

Dr John Geraint

“Tonypandy Square is the best place to begin.”

“The trouble with what I’ve written… is that it reads too much like a novel.”

Fifty years ago, and more, an excitable, bolshie Rhondda teenager decided he was destined to write a novel. Make that The Novel. And that one of the sentences quoted above should be the very first words of its Arresting Opening.

But which of the two sentences? He hesitated. He puzzled and pondered. And neglected to write the second sentence. Or any of the ones after that.

Pretty soon, life took him in a different direction. Because something else had happened in that long ago Rhondda past, something extraordinary. A neighbour of his had got to speak on the BBC.

What she said – about a local campaign – was very good, the other neighbours all agreed. But all the same, the way she’d said it struck them as unfortunate: “She did sound very Welsh, didn’t she?”

Uncouth

The excitable, bolshie teenager was appalled. To him, the only reason she’d sounded ‘very Welsh’ was that nobody else on the airwaves did. Literally nobody. People with working-class Welsh accents were never heard on TV or radio. So it was the context which made the neighbour seem uncouth, even to her own kind.

And if they thought that she didn’t belong on the BBC, it must mean they felt they didn’t belong there either. That what was natural to them was inferior, somehow.

The excitable, bolshie teenager knew that was wrong. Not just wrong, but important. And it became his mission in life to do something about it. To give a voice to those whose voices weren’t being heard, a broadcast platform for those whose experience and concerns were absent from the schedules.

So the Great Unfinished Novel was put aside.

To the documentary producer – for that’s what he then became – writing was, of course, a useful skill. Drafting a punchy memo to his bosses. Crafting a Radio Times billing. And – as the years went by – composing increasingly florid ‘proposals’ to sell basic ideas for documentaries to increasingly powerful commissioners.

But even the scripts he wrote for narration were so short that the producer never bothered to learn to type with more than two fingers. The guts of his work was elsewhere – on location, alongside the camera; in the cutting room; above all, in making relationships with the people whose lives needed to be documented.

Real writers

From time to time, he worked with people who were – or were becoming – real writers. Unmistakeably so.

One of our very finest poets and memoirists. A playwright of side-splitting Rhondda comedies. Wales’s first National Poet. A journalist who morphed into a prolific author of fact and fiction, not just the master of many different genres, in Welsh and English, but someone who supported the work of other writers, too, with a remarkable generosity of spirit.

And, still, somewhere in the back of the documentary-maker’s mind, those two opening sentences were circulating, nagging at him.

Eventually – the decades had flown past – he came to a crossroads in his career. It coincided with Lockdown. With filming on stop, he began to write. And write. And write. 150,000 words later (all of them typed with one or other of those two fingers!), he bucked up the courage to show the still incomplete draft novel to a friend, an experienced and distinguished author.

The feedback – basically: cut, cut, cut – was both strangely encouraging and utterly devastating at one and the same time. It took him months to face up to what needed to be done. But, in the end, do it he did.

And now things begin to move quickly. Another friend helps him identify a publisher. Who says ‘yes’. He’s a novelist!

Podcasts

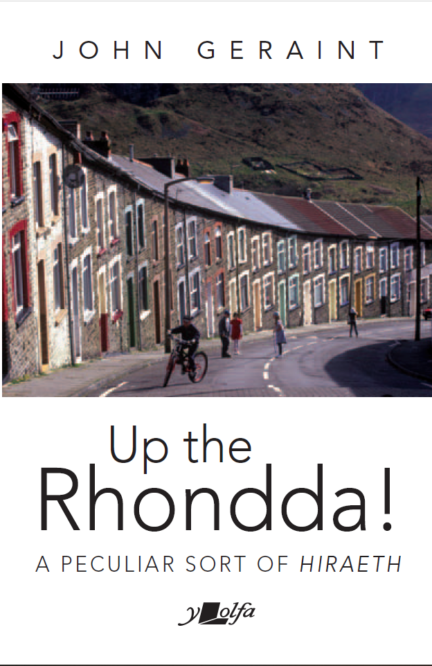

Soon, a second book, based on a long series of podcasts he’s recorded about his Rhondda upbringing, finds favour with another publishing house. And the original novel goes to a second edition and does so well that it’s now being relaunched with a spanking new cover, and a new title to boot.

And yet – compared with those authors whose work he’d grown to know and love through making programmes with them – he feels… well, at best a journeyman, at worst a downright fraud. His wife, a poet and author who undoubtedly has ‘the gift’, does her best to encourage him, pooh-poohing his conviction that he isn’t a ‘real writer’.

As the world opens up again, projects from his ‘previous life’ crowd in again. An exciting documentary series with a charismatic presenter new to TV history. The chance to lead a major heritage initiative in the Rhondda, combining people’s stories and memories – hundreds of them – with a Trail celebrating the valley’s astonishing industrial past.

Life – at any stage, and particularly at his mature one – shouldn’t be all about work. So he has to make choices. Does he have another book in him? What’s the best contribution he can make to the common good? What will give him true satisfaction? Is he really a writer? Is he a real writer? Or a writer at all?

Against the doubts stand the pleasures.

Heartfelt

In the busy-ness of preparing his books for publication, he somehow forgot that people would now actually be able to read them. It comes as a shock – and mostly an enjoyable one – to receive their responses. It obviously strikes a chord, his novel’s comic but heartfelt account of first love, lust and loss, of belonging and being different in a community on the cusp of epoch-defining change.

And the ‘peculiar kind of hiraeth’ he writes about in his second book seems to speak to valleys people and to others who yearn for a society where ‘what matters to us matters more than what matters to me’.

The critical response is kind too. More surprises manifest themselves.

He finds himself on stage in Y Babell Lên, the National Eisteddfod’s prestigious Literary Pavilion, in front of an audience of hundreds, being interviewed by that prolific and generous journalist-turned-author, as though he himself really is a real writer.

What pleases him most is that the single outlet that’s sold the largest number of copies of his books is… a fruit-and-veg shop in Treorchy.

His volumes are snapped up there daily, from right next to the carrots and cabbages. He imagines them being bought by the kind of people who – fifty years ago – were tricked into thinking that their accents didn’t belong on radio or TV. And who, even now, may have gleaned the impression that ‘literature’ isn’t really for them.

Oh – and there’s one final thing that tickles him. Those two alternative opening sentences from half a century back, the ones that kept the notion of writing alive in his mind for all those years?

With a sleight of hand that a real writer might be proud of, he’s managed to start his novel with… both of them!

John Geraint’s ‘The Great Welsh Auntie Novel’ has just been re-published by Cambria Books as ‘A Rhondda Romance’. www.cambriabooks.co.uk/product/a-rhondda-romance/

The compendium of his podcasts, ‘Up The Rhondda!’ is published by Y Lolfa www.ylolfa.com/products/9781800994874/up-the-rhondda!

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.