Part seven: The Great Welsh Auntie Novel by John Geraint

Nation.Cymru is delighted to publish the seventh part of documentary maker-turned-novelist John Geraint’s seriously playful “Great Welsh Auntie Novel” along with a reading by the author.

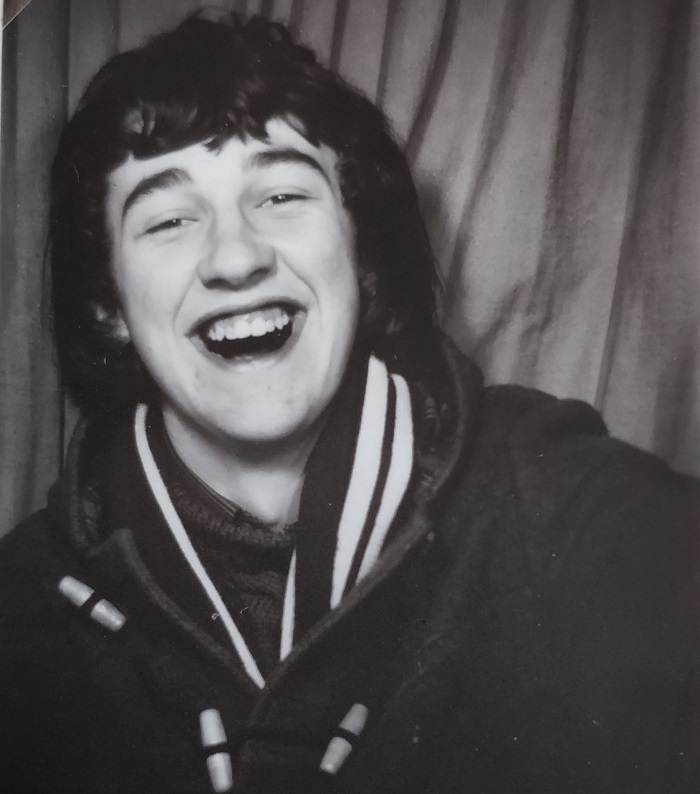

John Geraint

Seventeen-year-old Jac has vowed to grow up – and to ask Catherine out. As he travels up the Rhondda by bus on Election Night, February 1974, we’ve heard all about his chapel upbringing and his romantic obsessions with Welsh history and the radical politics of the coalfield. But now there’s another change of time and tone…

So that was the Rhondda in the 1970s, was it? Full of lefties, evangelicals and teenagers who revelled in their industrial history and knew their Pwyll Pendefig Dyfeds from their Ifor Haels?

I hear howls of protest from nearly everyone I grew up with.

Their Valley was never so political, never so chapel-dominated, never so fixated on its own past.

Never so Welsh, come to that.

How can I disagree?

I’ve already admitted being what my editor calls an unreliable narrator.

Put plainly, I’m making some of this up. It’s what novelists do.

(Confession: in Chapter 3, explaining where ‘Jac’ got the word ‘mole’ for a sea-wall from, I invented that bit about The Onedin Line script; although the series was on, and it features, in passing, later in this story. For the avoidance of doubt, the Rhondda Sea Cadets do exist and really are headquartered on Llwynypia Road).

Many of my classmates, far from loving the Rhondda so much that they wanted their ‘stories’ to go on being rooted here, couldn’t wait to get away.

Those who stayed were hardly as sentimental about their birthplace as ‘Jac’.

Why would they be?

Black spoil heaps on every horizon. A river black with coal-dust, still, despite the worked-out seams of the Black Diamond. Rotten housing stock. Empty, rotting places of worship. Dereliction all over the shop. All over the shops. Unemployment. Delinquency. Drugs.

Radical struggle

As for working-class solidarity, many ‘tidy’ people – those who scrimped and saved to make ends meet; chapel people too – tended to blame those worse off than themselves, rather than those who had more.

‘Scroungers’ and ‘wasters’ got fingers pointed at them far more often than fat cats and absentee landlords.

When things got a little easier, we turned as rapaciously consumerist as any other part of Britain.

Rhondda people loved treats and style and the fine things of life when they could afford them (and even if they couldn’t). And who’ll begrudge them that?

Nothing’s too good for the working class, as Nye Bevan is said to have said. But the working-class culture which had created the miners’ welfare halls and libraries, the co-ops, the self-governing non-conformist chapels – that culture had run out of steam, if it hadn’t collapsed completely.

My friends’ parents were watching Dick Emery and doing the Football Pools. Nothing distinctively Welsh or ‘woke’ about that.

The radical struggle of the Depression was the struggle of a bygone era: an unimaginably long time ago when the world was unimaginably different.

1910 and The Miners’ Next Step was more distant again.

Red past

A few of us did have the privilege of doing A level with a teacher who recognised that History is more than a list of (English) kings and queens. But, even then, our own history was an option taught for a term or two, not fundamental to our education.

So how could we have formulated a coherent analysis of it, let alone an Anarcho-Syndicalist one?

Rhondda’s ‘Red’ past did cast its shadow into the 1970s, it’s true.

When I first voted as an idealistic 18-year-old, it was for the veteran Communist Annie Powell – and she topped the poll in Penygraig, becoming Mayor of Rhondda.

(The first draft of this novel had a lovely section about ‘Jac’ and his friendship with Mrs Powell, complete with tales of her teaching Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau to Nikita Khrushchev on a visit to Moscow. My editor insisted I cut it: it was research, apparently, not narrative. ‘Research’! As though I’d had to research something I’d lived.)

Evolution not revolution

But, by 1974, Rhondda voters overwhelmingly backed Labour not the Communists; their socialism, to quote one of Rhondda’s most prominent – and now most discredited – parliamentarians, owed more to Methodism than to Marx.

Instinctively, like George Thomas, Viscount Tonypandy, former Speaker of the House of Commons, they sought change through parliamentary democracy, however left-wing their convictions.

Evolution not revolution.

So, I’ll have to concede that ‘Jac’ is far from representative.

His experience of evangelism is extreme (more of that later).

His interest in the Welsh language and Welsh history marks him out as an oddball in that time and place.

And as for his flirtations with revolutionary politics – his Auntie would have told him not to be so twp, so di-doreth.

She was one of those (or rather, as we shall see, fifty-two of those) who sided with Rhondda’s preference for constitutional reform, as distinct from militancy intended to overthrow the system.

She would have explained it to him with a gnomic juxtaposition, one of her nonsensical Rhondda sayings that may just be more profound than they seem.

“In a collision… well, there you are,” she’d have declaimed, pausing dramatically with a resigned, open-handed flourish. “In an explosion… where are you?”

The weight of the world

But if, as well as being hopelessly naïve, ‘Jac’ seems far too knowing for his age (and my editor says he does), there’s a couple of reasons for that.

The first is to do with that Auntie, who gives him access to a vast repository of experience. Trust me on this (no, really): there’s more about it to come.

The second is down to me. I don’t want to separate ‘Jac’ and his understandings – even if I was a good enough writer to do it – from lessons I’ve learned long after my schooldays.

Things about belief, about doubt, about history.

Things I’m still learning, about myself, about life.

Things, crucially, I’m only bottoming out as I write this now.

Defining, expanding, embracing that learning is what this novel is about.

Pinning it all on a teenager may be awkward, absurd, cruel even, unrealistic, I’ll give you that – but I can’t paint a useful picture of what the Rhondda was then, what it meant to me, what it might mean to us still, unless I burden ‘Jac’ with at least a little of what I know now.

Poor dab.

Stuck on a bus, carrying the weight of the world, and aching for all that learning to begin.

And for Catherine too.

Sorry, kid.

The Great Welsh Auntie Novel by John Geraint is published by Cambria Books and you can buy a copy here or in good bookshops.

You can catch up on previous extracts here. We’ll have another exclusive extract next week.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.