Part three: The Great Welsh Auntie Novel by John Geraint

Nation.Cymru is delighted to publish the third part of documentary maker-turned-novelist John Geraint’s seriously playful “Great Welsh Auntie Novel” along with a reading by the author.

John Geraint

17-year-old Jac is on a bus, travelling up the Rhondda Valley, with Petra and Lydia. They belong to an intense, tight-knit gang of teenagers which Petra has christened ‘The Society Of Friends’. Jac is worried about Petra’s boyfriend, the talented but troubled Martyn. He’s hoping that the bond of friendship which has drawn the group together can make a difference…

Now that bond would be reinforced, in the weeks of rehearsals that lay ahead for Twelfth Night. They could be fools, right enough – not just Penry who, with his fine, commanding baritone, would surely be cast as Feste, the singing jester – but all of them, pretty much, apart from Lydia. Idiots.

But somehow, Jac sensed, collectively in their nonsenses, and occasional good sense, they held the key to whatever was locked up inside Martyn. Just as they needed her, Petra needed them to help her make it right with Martyn.

Lydia with her calmness, her sureness of judgement. Penry with his music, his odd, intuitive notions, his quirky charm.

Jac himself, who was ‘wise enough to play the fool’ when everyone got too serious about themselves and how they felt about each other.

And yet scratch him and he too was a hopeless romantic, obsessed with history and place.

That was how Petra must regard him, anyway.

If his father was a miner rather than a teacher-cum-lay-preacher, she’d be thinking, he’d see things more like they really are.

But even Jac might be savvy enough to… Or was this all too convoluted, just fevered imaginings?

‘O Time, thou must untangle this, not I;

It is too hard a knot for me t’ untie!’

Real tragedy

Jac leaned forward. Petra and Lydia were talking about Catherine.

There’d been a tragedy in her family, a real tragedy, not a piece of illusory teenage angst.

Daniel, her step-brother – a couple of years older, but thin-skinned, volatile; a young man who seemed to depend on her – he had been found dead, hanged.

He was away in his first year at Swansea University. There was talk that he’d got a fellow student pregnant. A scandal, perhaps. But who knew that shame could be that lethal? This was 1974, not the nineteenth century.

The weekend before it had happened, Catherine told them that she was going down to Swansea, to help him sort it all out. There was a whisper that she herself had discovered the body.

How terrible, if true. But in whatever way it had come to light, she would be deep in shock.

“I can’t see her coming back to school,” Petra was saying. “Not until after the funeral, at the very least.”

“She won’t be there tonight, then?” Jac asked, just to keep the subject open.

“Definitely not. She could hardly bring herself to speak to me on the phone. It’s going to take a while, Jac… a long while, for her to get over this.”

Celtic gods

For Jac, Catherine was the one who made The Society of Friends work. And that was despite the fact – because of the fact – that she’d be the one outsiders would say was least likely to ‘make it’ (whatever that meant).

Her ordinariness made her special for Jac.

Since the autumn, they’d spent hours together, talking, listening to music – they shared the same taste, the same sense of humour, a fondness for the absurd.

Catherine liked to hear Jac reciting poetry, at least he was pretty sure she did. He’d begun to make a point of memorising verses he thought would appeal to her.

But she wasn’t going to be there tonight.

He forced his mind elsewhere.

They’d reached the junction by Glyncornel Lake. ‘Lake’? Pond, more like.

But there was magic in those waters, and peril, or so his Auntie used to tell him.

Fearsome Celtic gods dwell beneath its surface, appeased by ancient tribal offerings of weapons and jewellery, but ready to rise again if provoked…

The New Road

The bus ignored them, carrying straight on.

Away to the left, the New Road took the more direct route up the valley, through the Nant-y-Gwyddon woods, on to Gelli where Penry would be waiting to join them.

The New Road. Built by the unemployed as long ago as the Depression of the 1930s.

It had been in Jac’s thoughts for another reason.

In his head, he’d been writing The Great Rhondda Rock Song. Or trying to.

It celebrated this road, with its long, flat straights, the only highway on the whole Valley floor that wasn’t squeezed between houses and shops, an open invitation to teenage speedsters, on four wheels or two.

The chorus of Jac’s masterpiece-in-progress toasted the escapism it represented, the adrenalin rush of velocity.

Tonypandy Ton-Up,

Gonna take a run up

the New Road faster than light…

“Calm down, Jac,” That was Lydia, alarmed by the vibrations rumbling through her seat. “We’re not dancing yet.”

Without being conscious of it, he must have been beating out the song’s rhythm on the seat-back in front of him. He thrust his hands into his pockets. But the lyrics played on in his mind.

Flying in the car down to ’Pandy, smashed up like a bottle of coke,

Driving on a bottle of brandy is someone’s idea of a joke.

Several ironies were wrapped up in this nascent attempt at a classic hit.

One was that as a teetotal non-driver, Jac had no idea what a drunken racer might be feeling, careering at one-hundred-miles-an-hour through Tonypandy or anywhere else.

Just made the bend by the Plaza, can’t see the shade on the Lights,

Feeling like Samson in Gaza, it’s a Tonypandy Ton-Up tonight.

It was also true that he couldn’t play an instrument, hold a tune or even keep a rock-steady rhythm. His chances of becoming The World’s Top Teenage Rock’n’Roll Star were remote. He was the only person he’d ever heard of who’d failed the Grade I Piano exam.

“I’ve realised you’re not actually tone deaf,” Penry had told him once, overhearing him struggle with some solo acapella Bowie. “You’re just a vocal cripple.”

Gangly and underfed

So, now that he’d promised himself to grow up, shouldn’t he renounce these musical fantasies?

But… he’d already worked out a name for his band, and a look: raw and gawky, polar opposite to the puppyish charm of the Osmonds and David Cassidy.

Himself on vocals/rhythm guitar, three recruits who looked just as gangly and underfed on lead, bass and drums.

Jac and the Beanstalks.

Their string of hits would be one in the eye for James Taylor and everyone else back in Junior School who’d mocked his ignorance of pop music.

Well, a boy has to have a dream, or how would he ever get through the day?

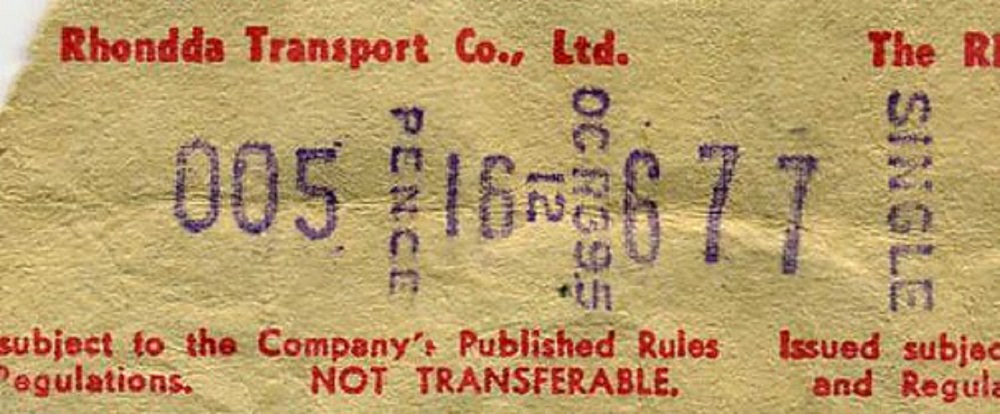

Jac realised he had been daydreaming. Again. A giant figure was towering over him, like a god risen from the waters of Glyncornel. Demanding to know what he wanted. It was the conductor.

“Single to the top of the charts, please, mister.”

Jac hoped his quip might get a cheap laugh. Or a cheap ticket.

The conductor curled his lip and punched out a return to Treorchy, on the basis that that’s what the two girls this joker was with had asked for.

Jac examined it: he’d been given a child’s half-fare. He blushed, coughed up the cash and went back to his music.

Thrills of speed

Tonypandy Ton-Up… it sounded good: it was cynghanedd – that resonant consonantal chime of Welsh bardic tradition – colliding playfully with the thrills of speed and Kerouac’s American roadsters.

All so very Jac. And authenticity was everything. So what if he couldn’t sing?

He’d recruit Beanstalks who weren’t musical either. Their incompetence would be their appeal.

It would put them on a level with their fans.

Why should stardom be the domain of the naturally gifted?

One day, maybe soon, Jac thought, music will be democratised, and virtuosity won’t count for so much.

The Great Welsh Auntie Novel by John Geraint is published by Cambria Books and you can buy a copy here or in good bookshops.

Part one can be read here and part two here. We’ll have another exclusive extract next week.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.